Prepared by

The Central Transportation Planning Staff

to the Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization

The Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization is composed of the following:

Massachusetts Department of Transportation

Metropolitan Area Planning Council

Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority

MBTA Advisory Board

Massachusetts Port Authority

Regional Transportation Advisory Council

City of Boston

City of Beverly

City of Everett

City of Framingham

City of Newton

City of Somerville

City of Woburn

Town of Arlington

Town of Bedford

Town of Braintree

Town of Lexington

Town of Medway

Town of Norwood

Federal Highway Administration (nonvoting)

Federal Transit Administration (nonvoting)

This document was funded in part through grants from the Federal Highway Administration and Federal Transit Administration of the US Department of Transportation. Its contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the US Department of Transportation.

Chapter 1 – Introduction and Process

Chapter 2 – Transportation Needs in the Boston Region

Chapter 3 – Funding the Transportation Network

Chapter 4 – The Recommended Plan

Chapter 5 – System Performance Report

Chapter 6 – Transportation Equity Performance Report

Chapter 7 – Air Quality Conformity Determination and Greenhouse Gas Analysis

Chapter 8 – Next Steps: Implementation of Destination 2040

Appendix A – Universe of Investment Programs and Projects

Appendix B – Destination 2040 Project Evaluation Methodology

Appendix D – Public Outreach for Destination 2040

The MPO complies with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and other federal and state nondiscrimination statutes and regulations in all programs and activities. The MPO does not discriminate based on race, color, national origin (including limited English proficiency), religion, creed, gender, ancestry, ethnicity, disability, age, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, veteran’s status (including Vietnam-era veterans), or background. Any person who believes herself/himself or any specific class of persons to have been subjected to discrimination prohibited by Title VI, ADA, or another nondiscrimination statute or regulation may, herself/himself or via a representative, file a written complaint with the MPO. Complaints filed under federal law (based on race, color, national origin [including limited English proficiency], sex, age, or disability) must be filed no later than 180 calendar days after the date the person believes the discrimination occurred. Complaints filed under Massachusetts General Law (based on race, color, religious creed, national origin, sex, sexual orientation, disability, or ancestry) or Governor’s Executive Order 526, section 4 (based on race, color, age, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, religion, creed, ancestry, national origin, disability, veteran’s status [including Vietnam-era veterans], or background) must be filed no later than 300 calendar days after the date the person believes the discrimination occurred. A complaint form and additional information can be obtained by contacting the MPO (see below) or at www.bostonmpo.org.

The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority, Cape Ann Transportation Authority, and MetroWest Regional Transit Authority, which are Federal Transit Administration Section 5307(c) applicants, have consulted with the MPO and concur that the public involvement process adopted by the MPO for the development of the Transportation Improvement Program satisfies the public hearing requirements that pertain to the development of the Program of Projects for regular Section 5307, Urbanized Area Formula Program, grant applications, including the provision for public notice and the time established for public review and comment.

Boston Region MPO

Certification Activities Group, Central Transportation Planning Staff

10 Park Plaza, Suite 2150

Boston, MA 02116

857-702-3690 (voice), 617-570-9193 (TTY)

This document, Destination 2040, is the Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization’s (MPO) Long-Range Transportation Plan (LRTP) that will guide decisions about investments in the region’s transportation network to bring the system from its present state towards the MPO’s vision for the system’s future:

The Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization envisions a modern, well-maintained transportation system that supports a sustainable, healthy, livable, and economically vibrant region. To achieve this vision, the transportation system must be safe and resilient; incorporate emerging technologies; and provide equitable access, excellent mobility, and varied transportation options.

To help achieve the MPO’s vision, this LRTP identifies goals, evaluates needs, and sets priorities, which will be supported with federal funding that the MPO receives for planning and programming investments in capital projects. However, given the region’s aging transportation infrastructure and limited resources, the MPO continues to address the following challenge through this LRTP:

How can we maintain the transportation network to meet existing needs, adapt and modernize it for future demand, and simultaneously work within the reality of constrained fiscal resources?

The MPO recognizes the diverse transportation needs in the Boston region. Matters of system preservation and modernization, safety, capacity management and mobility, the environment, economic vitality, and environmental justice all must be addressed and balanced to reach the MPO’s goals. In response to this challenge, the Recommended Plan demonstrates the MPO’s method for providing adequate funding for major infrastructure projects and investment programs.

During the development of the previous LRTP, Charting Progress to 2040, the MPO reevaluated its past practices and set a new course by moving away from programming funding predominantly for expensive capital-expansion projects designed to ease traffic congestion and instead set aside more funding for small operations-and-management-type projects that support bicycle, pedestrian, and transit projects, along with major roadway improvements. Destination 2040 continues this practice and increases funding for operations-and-management programs.

The MPO developed Destination 2040 in compliance with the current federal highway legislation, Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act, which governs MPO activities. In addition, public participation provided ongoing critical input to the MPO’s decision-making process. Throughout development of this LRTP, the MPO engaged in extensive outreach with an eye toward making public participation convenient, inviting, and engaging for everyone. In particular, the MPO sought to break down barriers to participation for people who traditionally have been only minimally involved in the continuous, comprehensive, cooperative (3C) planning process, such as minority and low-income populations, people who are 75 years of age or older, people who are 17 years of age or younger, and those with limited English proficiency (also referred to as LEP) or disabilities. These outreach efforts were conducted through the MPO’s Public Participation Program, which has focused on expanding the use of electronic forms of communication and interactive engagement techniques.

Early in the process of developing Destination 2040, the region’s transportation needs were assessed to help the MPO board decide which projects to fund in the LRTP. The Needs Assessment associated with Destination 2040 includes information about how the region’s surface transportation system is used now; projections of how it may be used in the future; how it interacts with land use conditions and the environment; and how well it serves low-income, minority, and other historically underserved populations. The Needs Assessment also establishes the baseline for monitoring progress through the MPO’s performance-based planning process.

The Needs Assessment data are available on the MPO’s website to help inform the public and make the planning process more transparent. The Needs Assessment document, also found on the MPO’s website, summarizes these data and identifies the region’s most critical needs relative to each of the MPO’s goals. The Needs Assessment makes clear that the transportation system requires extensive maintenance and modernization, and that there is a need to address safety and mobility for all modes.

Using the Needs Assessment and input from the public, the MPO staff compiled a comprehensive Universe of Projects and Programs that could be funded to address the identified problems; the projects and programs selected for evaluation and inclusion in this LRTP were taken directly from this list.

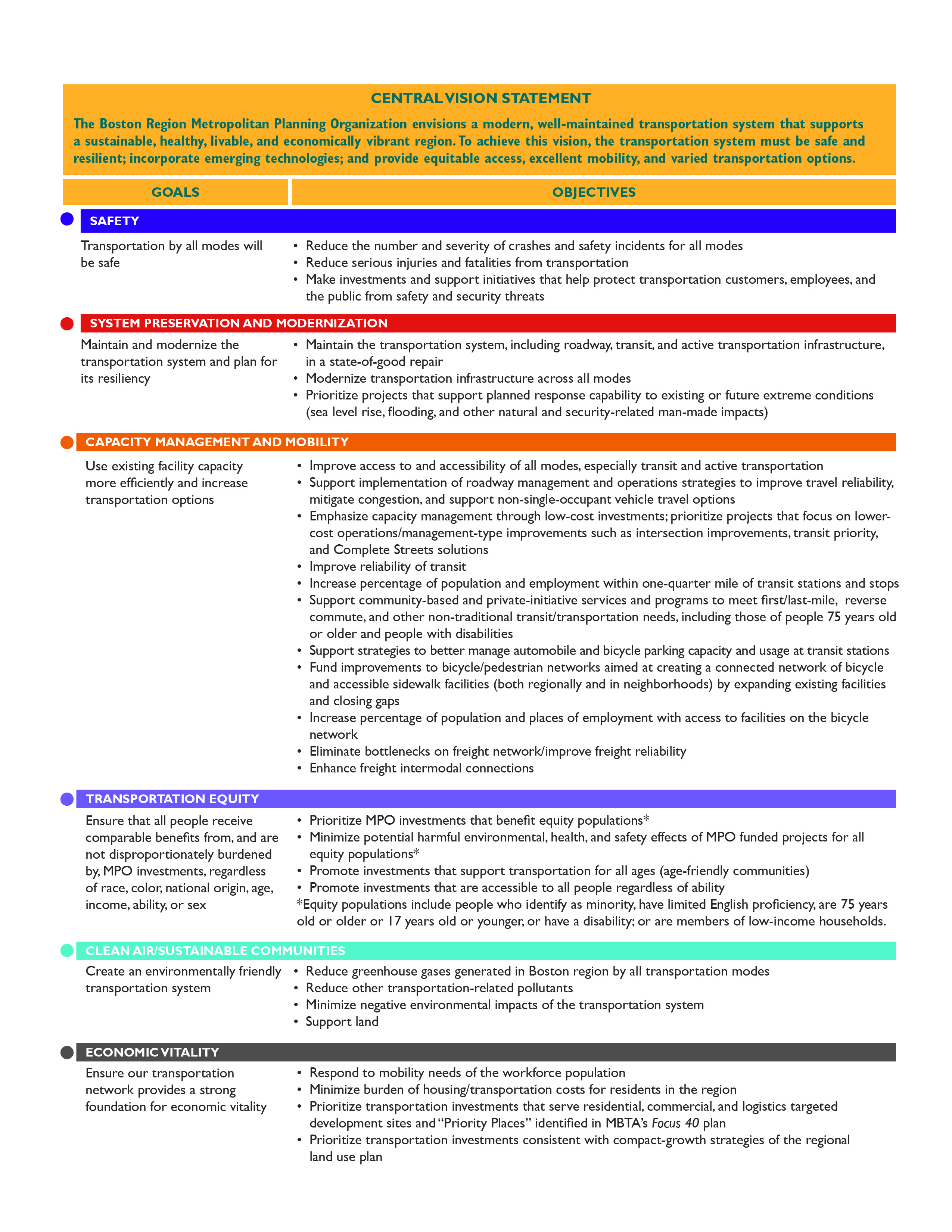

The MPO considered the public input provided during the development of the Needs Assessment for Destination 2040 when revisiting its existing vision, goals, and objectives. Based on that input, the MPO revised its vision statement to include additional emphasis on the maintenance and resilience of the transportation system. The MPO and public continue to envision the future transportation system by focusing on goals associated with these topics:

Public input was also taken into account when the MPO revised several of the objectives for each goal area. In addition to strengthening objectives focused on maintenance and resiliency of the system, changes were also made to the transportation equity objectives. Other changes included alignment of the objectives with the roles and responsibilities of the MPO and the incorporation of new planning requirements.

The goal areas were used by the MPO to categorize problems and their associated requirements for the transportation network in the Needs Assessment. This structure allowed the MPO to set goals that, if accomplished, would result in solutions for the identified problems and help the region achieve its vision. (See Figure ES-1.)

Figure ES-1

Destination 2040 Vision, Goals, and Objectives

Central Vision Statement

The Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization envisions a modern, well-maintained transportation system that supports a sustainable, healthy, livable, and economically vibrant region. To achieve this vision, the transportation system must be safe and resilient; incorporate emerging technologies; and provide equitable access, excellent mobility, and varied transportation options.

GOALS |

OBJECTIVES |

Safety |

|

Transportation by all modes will be safe |

• Reduce the number and severity of crashes and safety incidents for all modes |

System Preservation and Modernization |

|

Maintain and modernize the transportation system and plan for its resiliency |

• Maintain the transportation system, including roadway, transit, and active transportation infrastructure, in a state of good repair |

Capacity Management and Mobility |

|

Use existing facility capacity more efficiently and increase transportation options |

• Improve access to and accessibility of all modes, especially transit and active transportation • Support implementation of roadway management and operations strategies to improve travel reliability, mitigate congestion, and support non-single-occupant vehicle travel options • Emphasize capacity management through low-cost investments; prioritize projects that focus on lower-cost operations/management-type improvements such as intersection improvements, transit priority, and Complete Streets solutions • Improve reliability of transit • Increase percentage of population and employment within one-quarter mile of transit stations and stops

|

Transportation Equity |

|

Ensure that all people receive comparable benefits from, and are not disproportionately burdened by, MPO investments, regardless of race, color, national origin, age, income, ability, or sex |

• Prioritize MPO investments that benefit equity populations* |

Clean Air/Sustainable Communities |

|

Create an environmentally friendly transportation system |

• Reduce greenhouse gases generated in Boston region by all transportation modes |

Economic Vitality |

|

Ensure our transportation network provides a strong foundation for economic vitality |

• Respond to mobility needs of the workforce population

|

Source: Boston Region MPO.

Together, the vision, goals, and objectives lay the groundwork for the MPO’s performance-based planning practice, which in turn informs all of the work conducted by the MPO and includes evaluating and selecting projects and programs for the LRTP, selecting projects for the Transportation Improvement Program (TIP), and selecting planning studies for the Unified Planning Work Program.

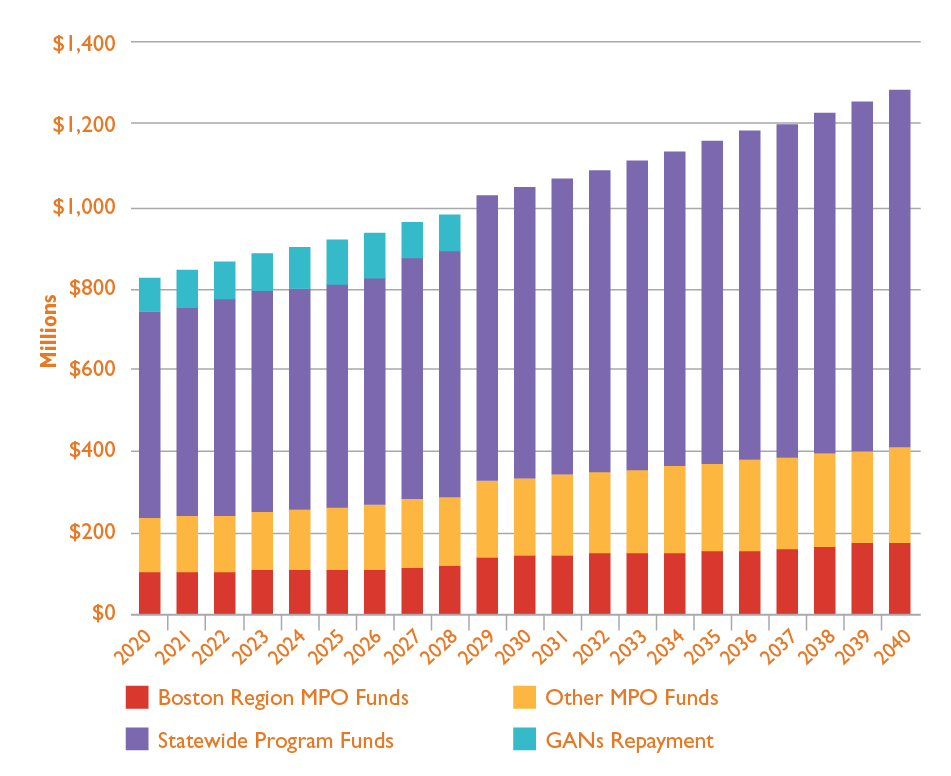

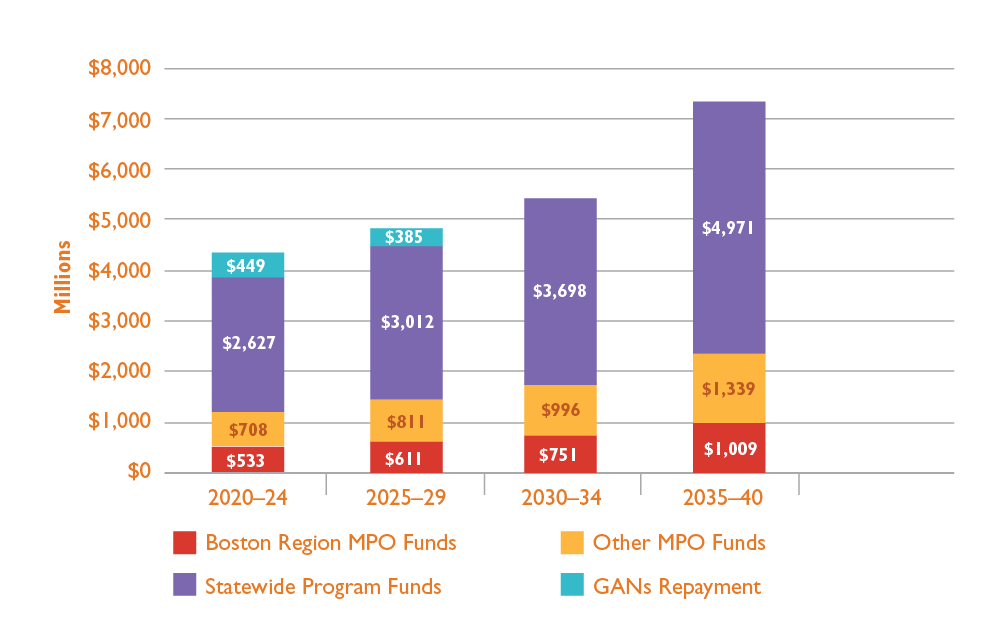

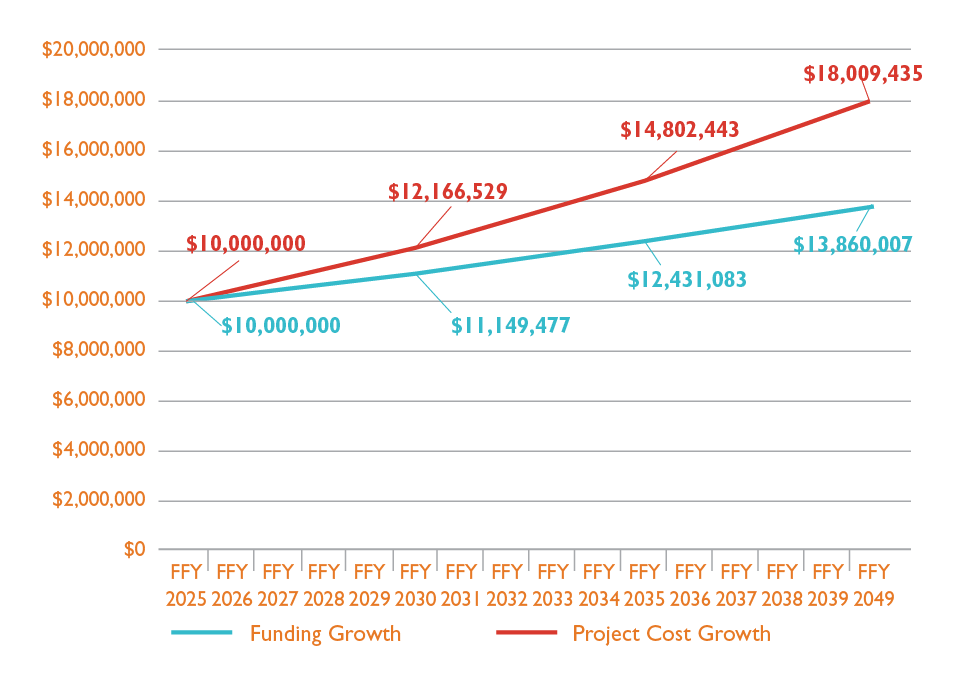

During the 20 years of this plan, the Boston Region MPO has the discretion to program $2.9 billion in federal funds, which can be spent on highway transportation projects or flexed to transit projects. The federal agencies advised MassDOT and the MPO to assume that federal highway funding for MPOs would increase by 2.2 percent each year for federal fiscal years (FFYs) 2025 through 2040. For the same period, the MPO was told to assume that project costs would inflate by four percent each year. If these assumptions hold true, project costs will outpace available revenues resulting in diminished buying power in future years.

The financial plan for Destination 2040, which is discussed in Chapter 3, reflects the way in which the MPO plans to balance how it addresses the diverse identified needs while operating under the fiscal constraint of projected revenues. The financial plan includes estimated costs for the specific regionally significant transportation projects that the MPO will fund as well as defined amounts of money set aside throughout the life of the plan for programs that will fund smaller projects. Because these smaller projects are not regionally significant, they are not accounted for individually in the LRTP; rather they will be selected through the TIP programming process.

In addition to reporting on the MPO’s spending decisions, this financial plan provides information on the funds that the Commonwealth plans to spend on highway projects in the Boston region. It also describes expected resources available to the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA), the Cape Ann Transportation Authority, and the MetroWest Regional Transit Authority to provide and improve transit service in the region.

Destination 2040 reaffirms the MPO’s policy of setting aside discretionary funding for a set of investment programs, continuing an operations-and-management approach to programming, and giving priority to low-cost, non-major infrastructure projects. The MPO agreed to continue funding the following existing investment programs, which are designed to prioritize the types of transportation projects that the MPO funds through its TIP

In addition, based on information from the Needs Assessment and public input, the MPO voted to

In addition to establishing this set of investment programs, the MPO also revised its funding goals for each of the investment programs as follows:

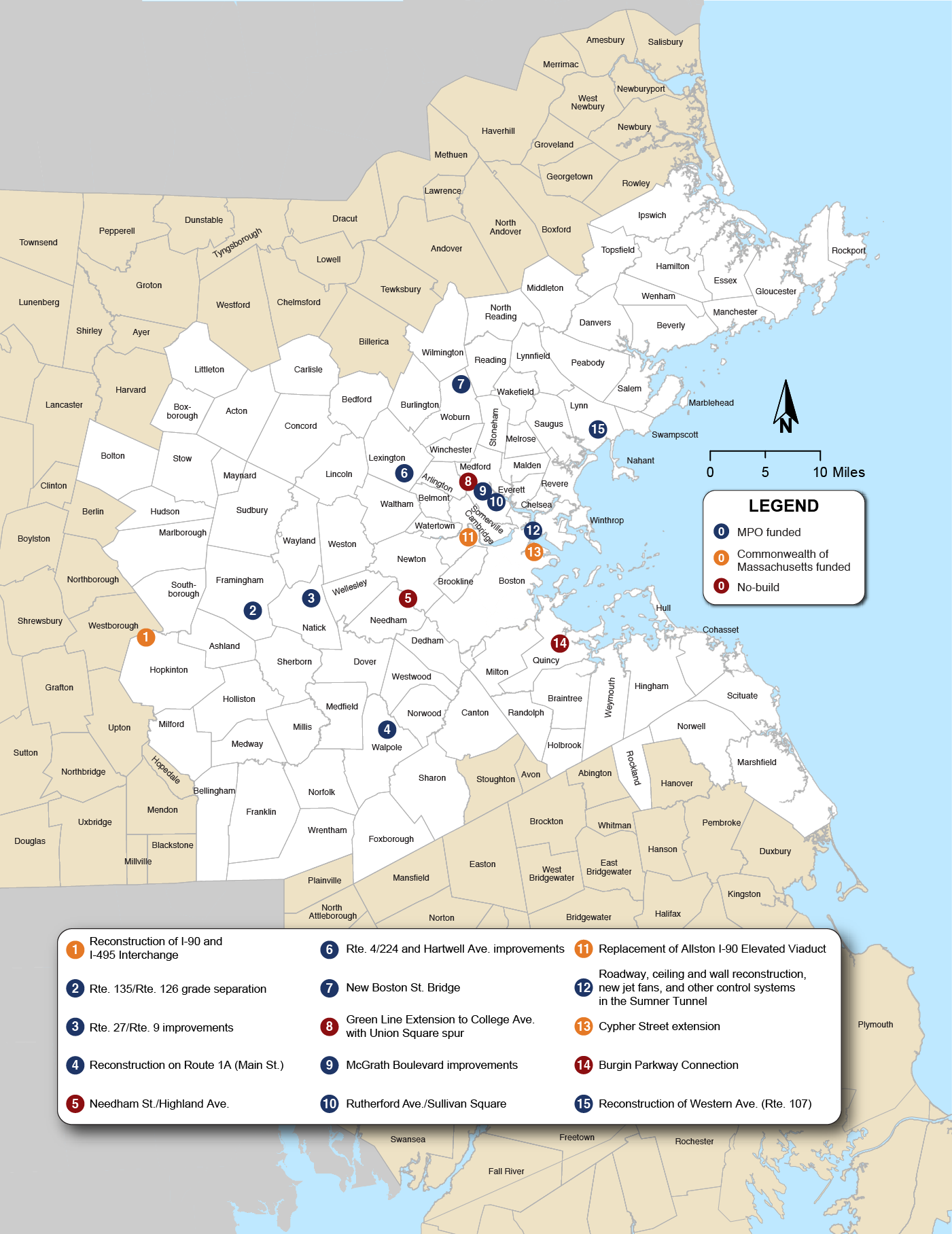

Major infrastructure projects that are funded by the MPO and included in Destination 2040 are shown in Table ES-1.

Table ES-1

Major Infrastructure Projects Funded by the Boston Region MPO in the Recommended Plan

Project Name |

Current Cost |

Time Band(s) Programmed |

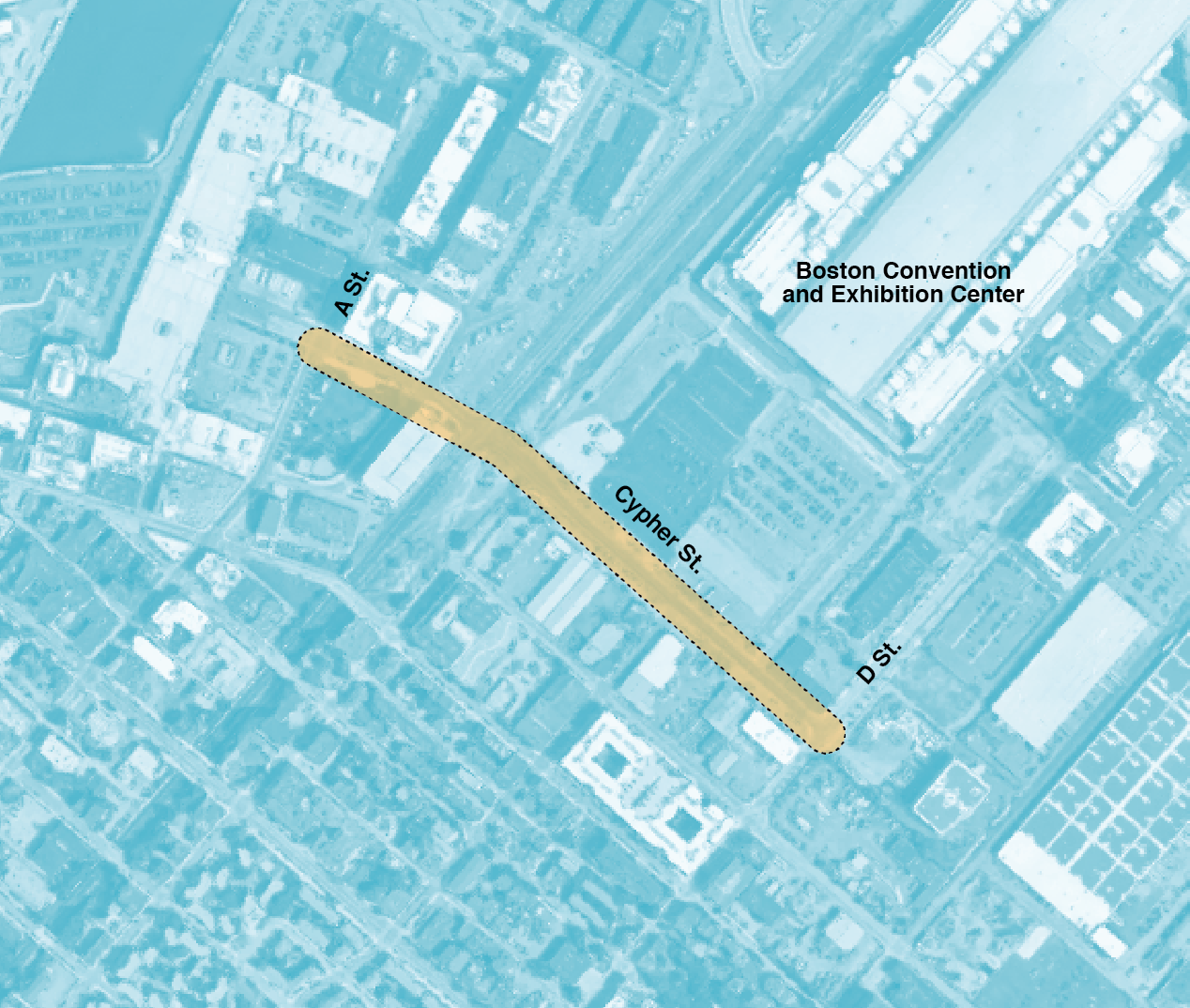

Reconstruction of Rutherford Avenue, from City Square to Sullivan Square (Boston) |

$152,000,000 |

FFY 2020–29 |

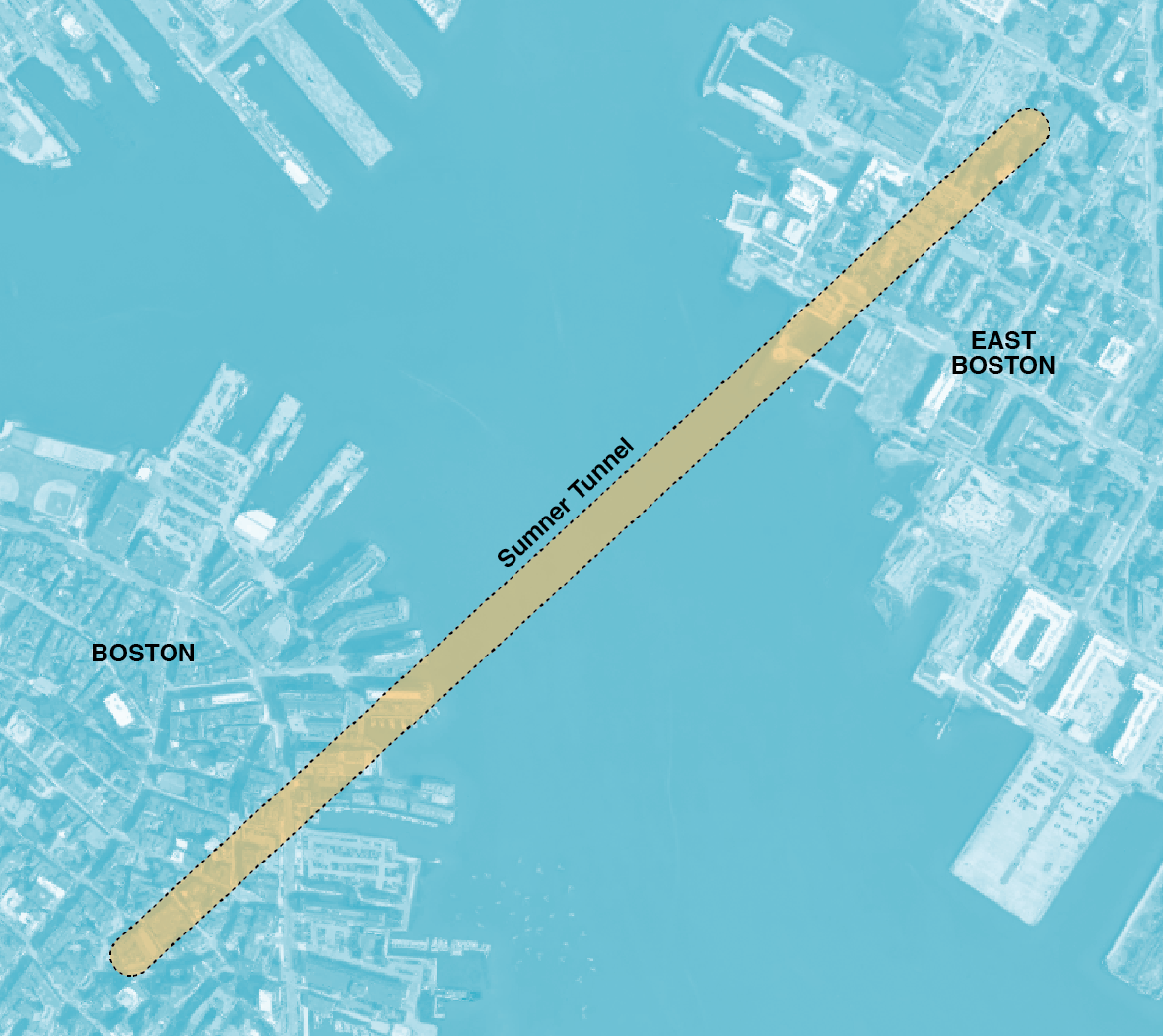

Roadway, ceiling, and wall reconstruction, new jet fans, and other control systems in Sumner Tunnel (Boston) |

$126,544,931 |

FFY 2020–24 |

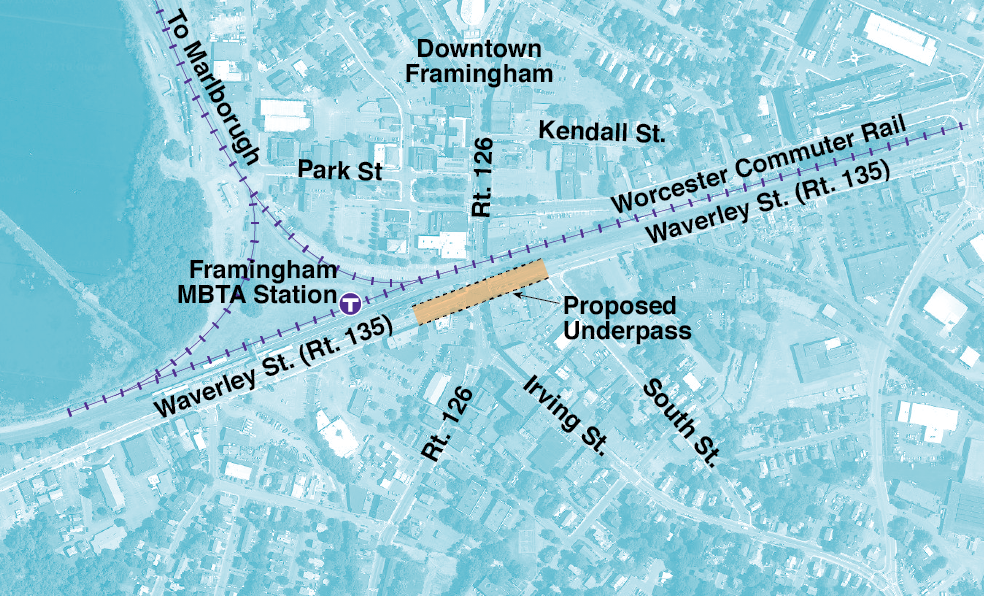

Intersection improvements at Route 126 and Route 135/MBTA and CSX Railroad (Framingham) |

$115,000,000 |

FFY 2030–40 |

Route 4/225 (Bedford Street) and Hartwell Avenue (Lexington) |

$30,557,000 |

FFY 2030–34 |

Western Avenue (Lynn) |

$36,205,000 |

FFY 2025–29 |

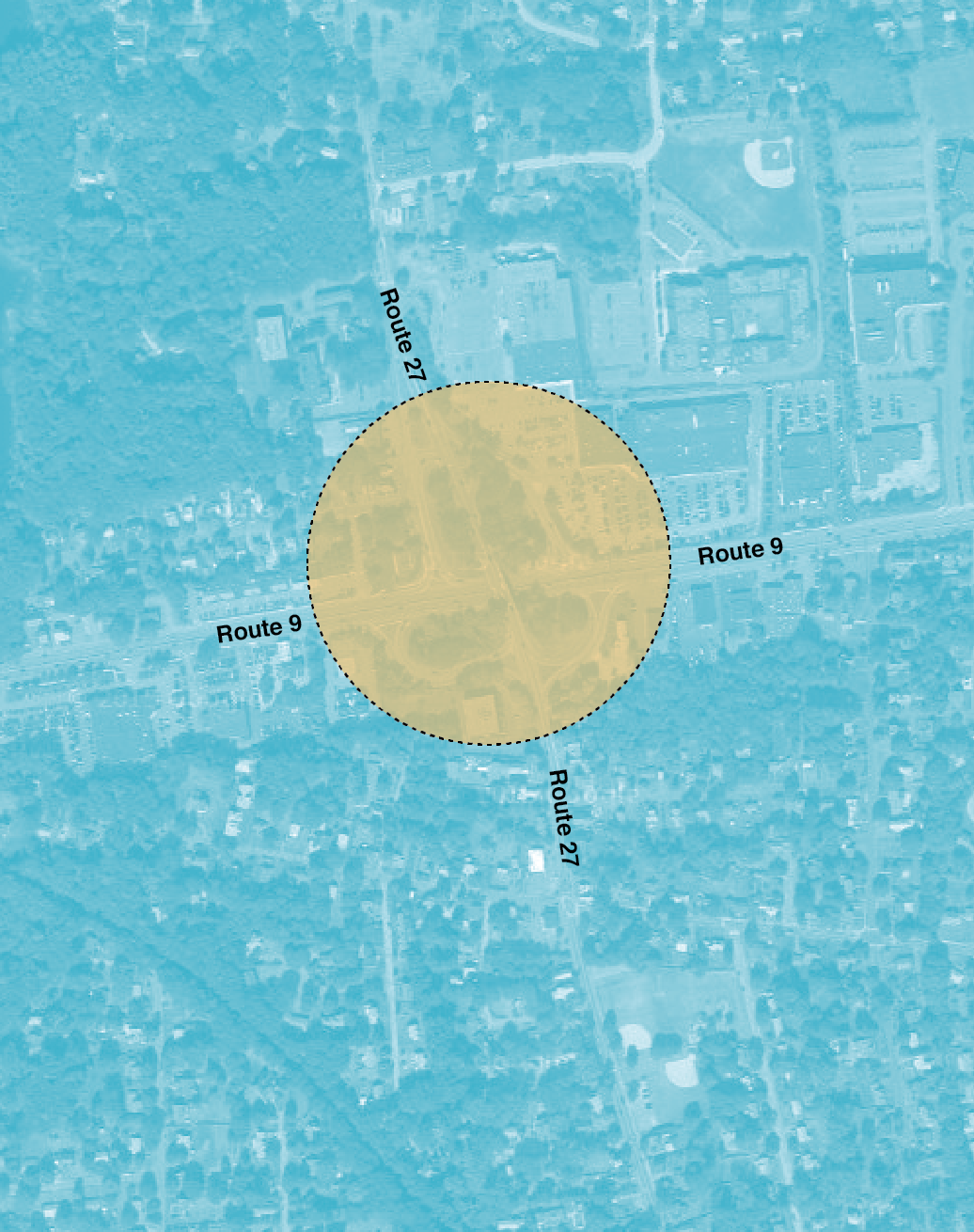

Bridge replacement, Route 27 (North Main Street) over Route 9 (Worcester Street) and interchange improvements (Natick) |

$25,900,000 |

FFY 2025–29 |

McGrath Boulevard (Somerville) |

$66,170,710 |

FFY 2025–34 |

Reconstruction of Route 1A (Main Street) (Walpole) |

$19,906,000 |

FFY 2020–24 |

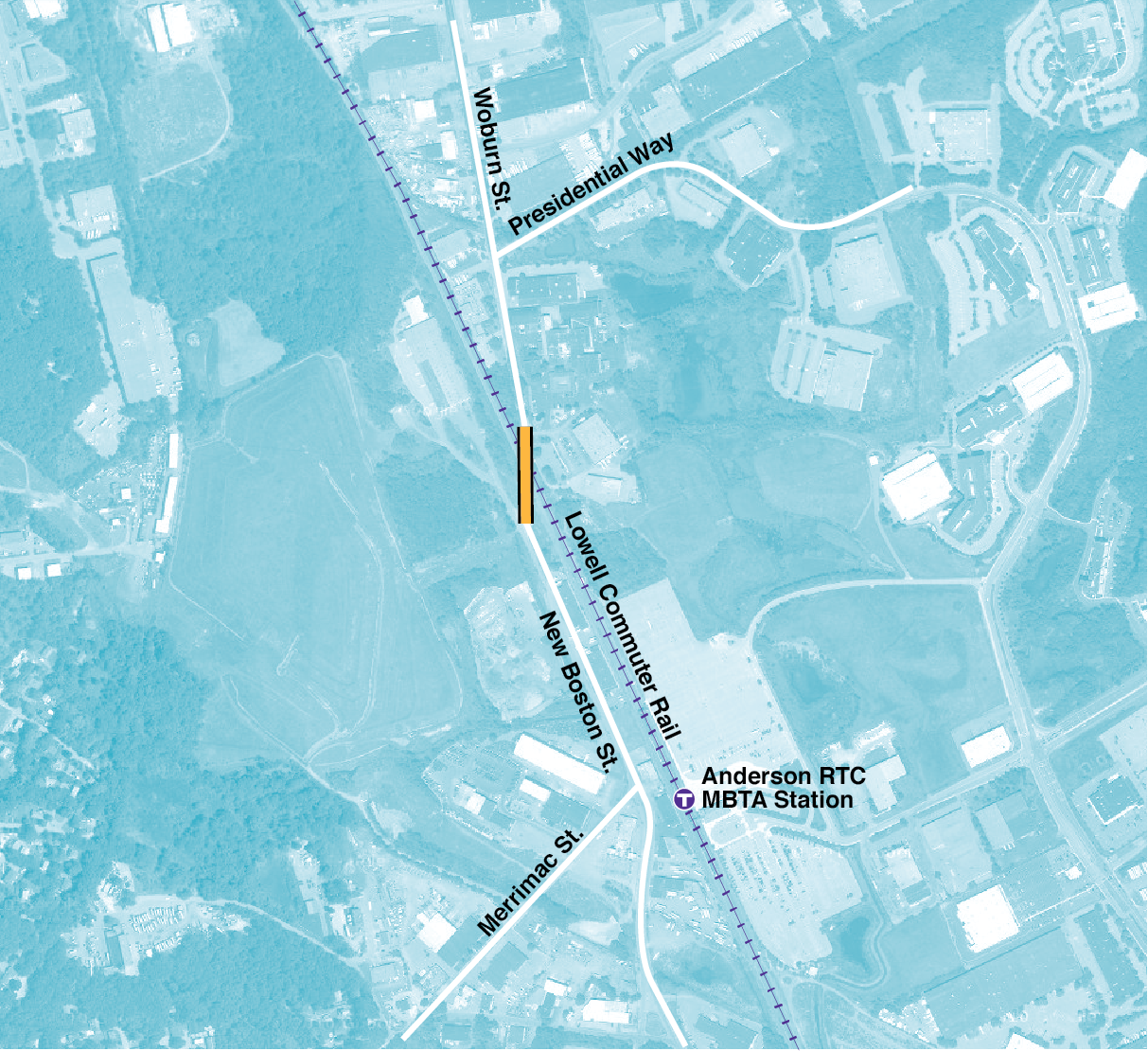

Bridge replacement, New Boston Street over the MBTA (Woburn) |

$15,482,000 |

FFY 2020–24 |

FFY = Federal Fiscal Year. MBTA = Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. MPO = Metropolitan Planning Organization.

Source: Boston Region MPO.

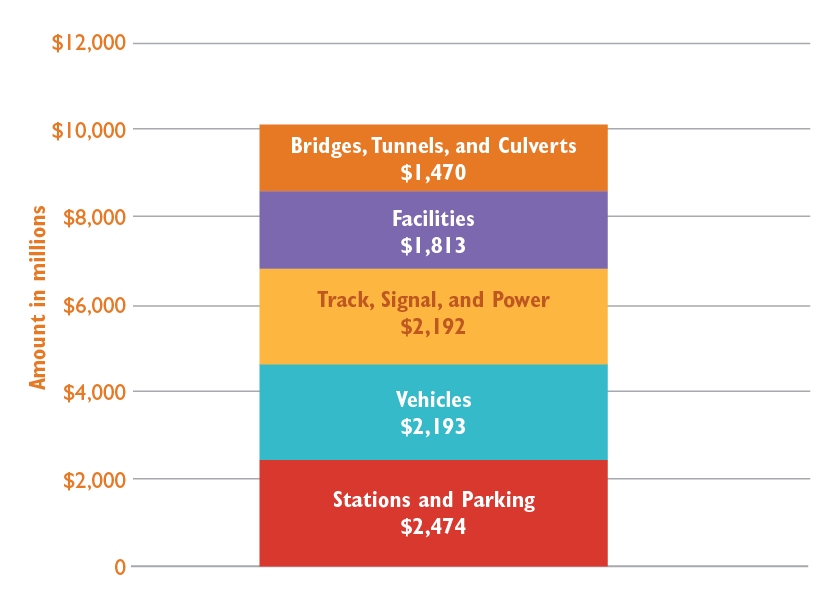

In Destination 2040, for the transit network, the MPO has allocated all of the MBTA’s future transit capital funding to system infrastructure maintenance, accessibility improvements, and system enhancements. Destination 2040 also demonstrates the MPO’s commitment to projects in the State Implementation Plan by programming and funding them.

Table ES-2 presents a list of the amount of funding dedicated to programs in Destination 2040.

Table ES-2

Funding Dedicated to MPO Investment Programs in Destination 2040

Program |

Dedicated Funding |

MPO Discretionary Capital Program: Major Infrastructure Projects |

$594,099,800 |

MPO Discretionary Capital Program: Highway Funds Flexed to Transit |

$49,131,200 |

MPO Discretionary Capital Program: Complete Streets Program |

$1,296,464,600 |

MPO Discretionary Capital Program: Intersection Improvement Program |

$367,057,800 |

MPO Discretionary Capital Program: Bicycle/Pedestrian Program |

$139,360,300 |

MPO Discretionary Capital Program: Community Connections Program |

$55,413,900 |

MPO Discretionary Capital Program: Transit Modernization Program |

$118,534,700 |

MPO Discretionary Capital Program: Unassigned Funds |

$283,798,100 |

Total MPO Funding |

$2,903,860,400 |

MPO = Metropolitan Planning Organization.

Source: Boston Region MPO.

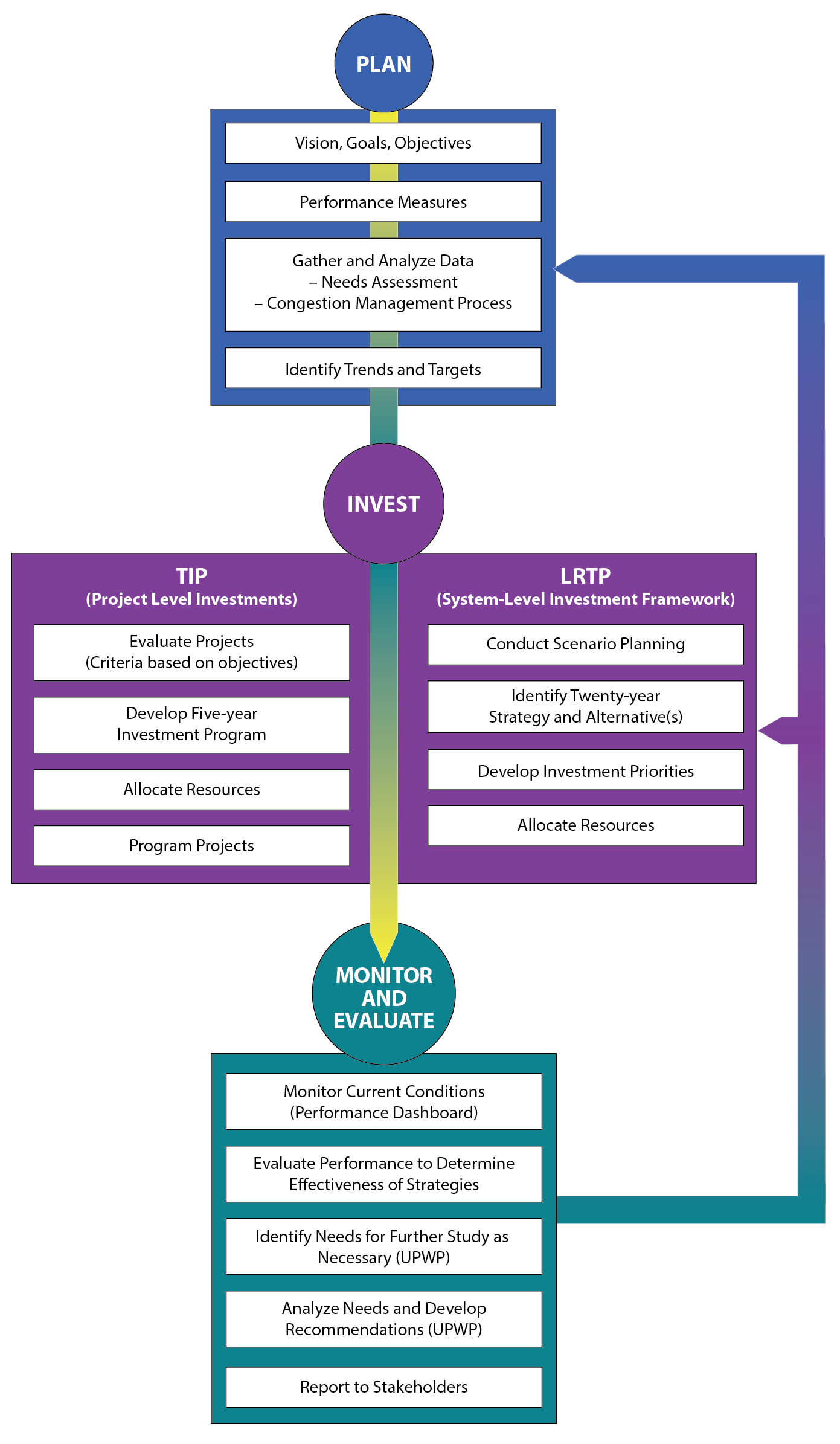

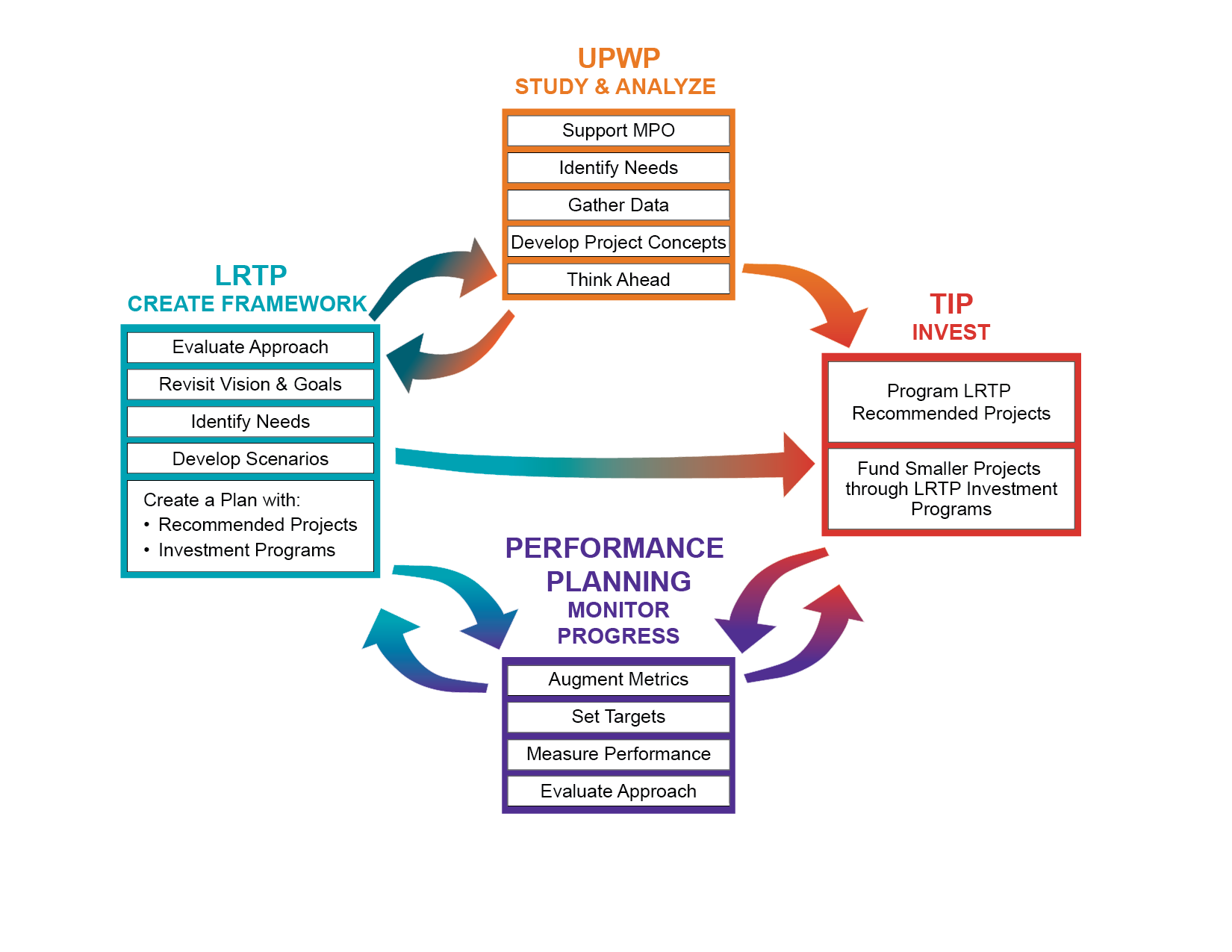

During the life of Destination 2040, the Boston Region MPO will continue its transition to a performance-based approach to making investments in the region’s transportation system. The MPO’s performance-based planning and programming (PBPP) practice is focused on ensuring that transportation investment decisions are oriented toward meeting established goals. PBPP activities generally fall into three phases:

The MPO’s PBPP process includes activities that respond to federal PBPP requirements. States, public transportation agencies, and MPOs must set targets for, monitor, and report on performance in a number of defined performance areas with the goal of improving performance in these areas through transportation investments. Table ES-3 lists these performance areas.

Table ES-3

Federal Performance Areas and Performance Measure Topics

Performance Area |

Performance Measure Topics |

Transit Safety |

Fatalities Injuries Safety events System reliability |

Transit Infrastructure Condition |

Vehicle condition Facility condition Infrastructure (fixed-guideway) condition |

Roadway Safety |

Fatalities, including for nonmotorized users Serious injuries, including for nonmotorized users Fatality rates Serious injury rates |

NHS Infrastructure Condition |

NHS bridge condition NHS pavement condition |

NHS System Performance |

Travel time reliability (all vehicles) on the NHS Truck travel time reliability on the NHS |

CMAQ–Traffic Congestion |

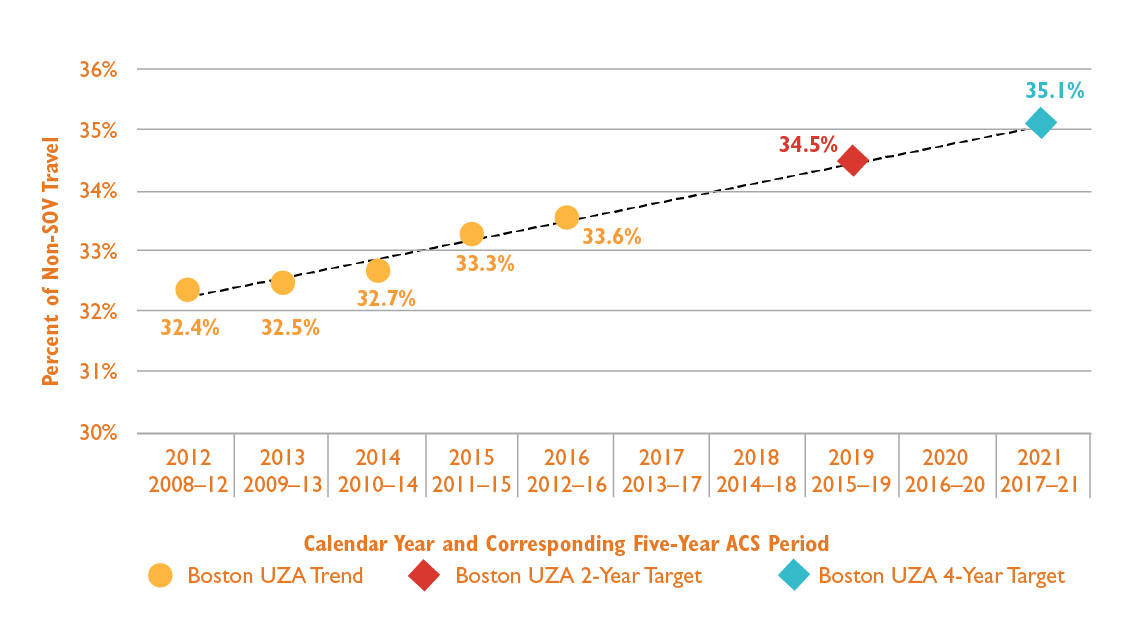

Peak hour excessive delay on NHS roadways Share of non-SOV travel |

CMAQ–Emissions Reduction |

Emissions reductions from projects funded through the CMAQ Program in designated air quality improvement areas |

CMAQ = Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality. MPO = Metropolitan Planning Organization. NHS = National Highway System. Non-SOV = non-single occupancy vehicle.

Sources: Boston Region MPO, Federal Highway Administration, and Federal Transit Administration.

To meet federal requirements, the MPO’s LRTP must

Chapter 5 of Destination 2040 lists federally required performance measures and targets and describes the state of the Boston region’s transportation system with respect to these measures. Additional information about the state of the system is available in the Needs Assessment.

The LRTP also outlines an investment framework, based on the MPO’s goals and objectives, and the projects and programs that are designed to improve transportation performance in these and other areas. Chapter 5 outlines how Destination 2040’s regionally significant projects and investment programs may improve performance in federal performance areas. These long-term investment strategies will inform the short-term capital investment decisions the MPO makes each year in the TIP. Finally, Chapter 5 explains how the MPO will report on performance and expand its PBPP practice in the future.

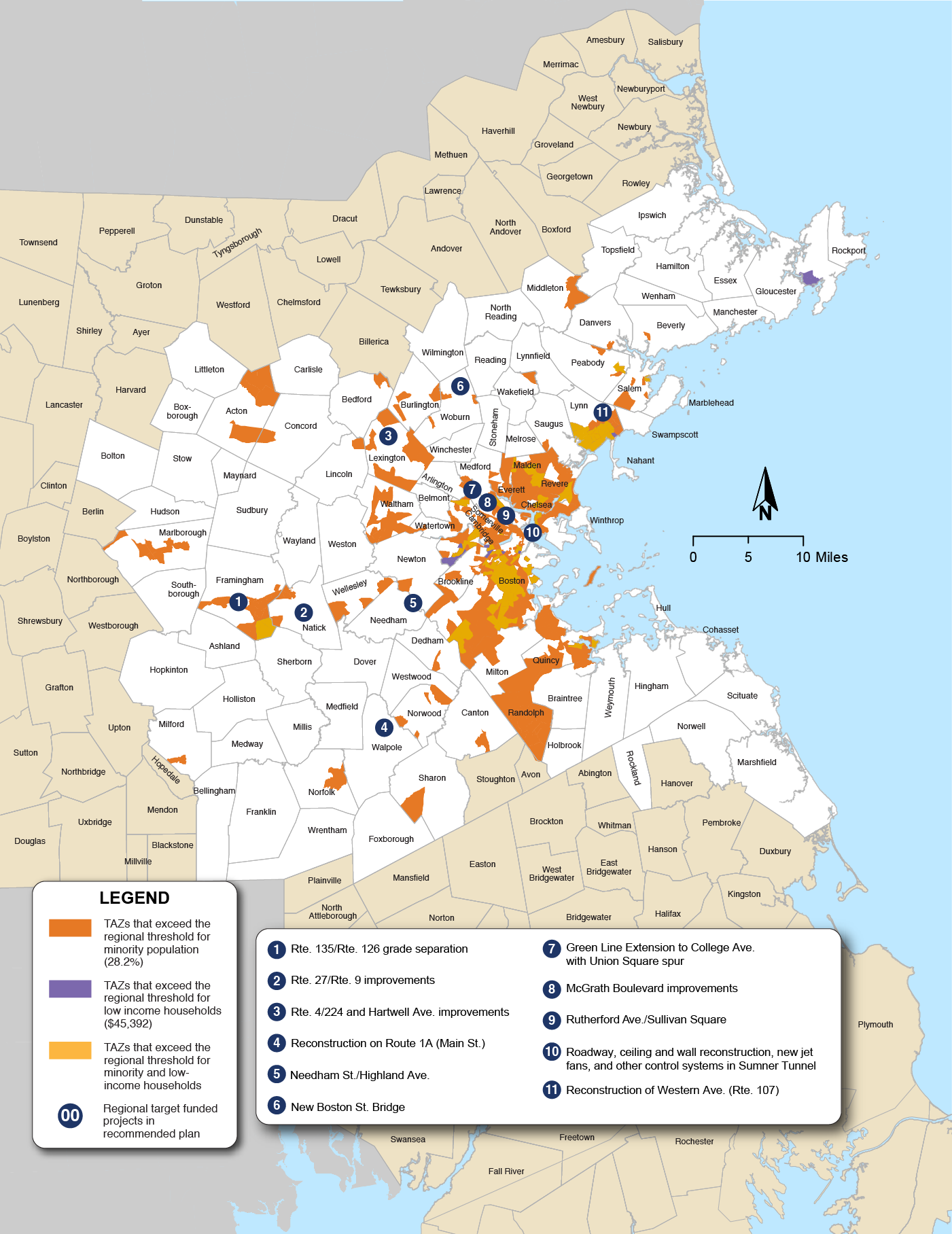

As a recipient of federal funding from the Federal Transit Administration and the Federal Highway Administration, the MPO must comply with federal Title VI, environmental justice (EJ), and other nondiscrimination requirements promulgated by these agencies. Chapter 6, the Transportation Equity Performance Report, documents the MPO’s compliance with Title VI and EJ analytical requirements as they pertain to the LRTP. The chapter includes a map of the projects in the Recommended Plan overlaid on areas with high shares of minority and/or low-income populations and a disparate impact and disproportionate burden (DI/DB) analysis that determined whether minority and low-income populations may be disproportionately affected by the projects in the Recommended Plan that can be modeled, in the aggregate, in the MPO’s regional travel demand model.ES-1

The DI/DB analyses, which are designed to meet both Title VI disparate impact and EJ analytical requirements, identified potential future disparate impacts that may result from the modeled projects and affect minority populations, as well as potential future disproportionate burdens that may affect low-income populations.ES-2 Adverse effects may be either a delay or denial of benefits or an imposition of burdens. For this LRTP, MPO staff used the regional travel demand model to assess ten metrics for potential future disparate impacts and disproportionate burdens in both sets of analyses:

Two scenarios were tested in the travel demand model to identify the projected impacts, as measured by these metrics, of the proposed transportation network on minority, low-income, nonminority, and non-low-income populations. In one scenario, the transportation network as envisioned for the year 2040 included the modeled projects (a build scenario) and another 2040 scenario did not include them (a no-build scenario). The changes between the build and no-build scenarios for the minority and low-income populations were compared to the changes between the nonminority and non-low-income populations, respectively.

Finally, MPO staff applied the MPO’s draft DI/DB Policy to determine whether this comparison revealed any disparate impact for the minority population or disproportionate burden for the low-income population. The DI/DB Policy, in effect for the first time during the development of Destination 2040, states how the MPO identifies and addresses potential future disparate impacts and disproportionate burdens that may result from the modeled projects in the Recommended Plan. In FFY 2018, MPO staff began the first of a two-phase effort to develop a DI/DB policy for the modeled projects; the second phase will begin in FFY 2020 and the draft policy will be revised to reflect this work. The current draft DI/DB Policy states that there would be a potential future disparate impact or disproportionate burden if the minority or low-income populations would likely be more adversely affected than the nonminority or non-low-income populations, respectively, assuming the finding is not skewed by a forecasting error for the metric.

The DI/DB analyses showed that no disparate impacts and disproportionate burdens would likely result from either the MPO-funded regional projects or the MassDOT and MPO-funded regionally significant projects.

The MPO staff completed two types of air quality analyses for Destination 2040. The first is the air quality conformity determination for projects in the LRTP, as required by federal and state regulations, which specifically addresses ozone and carbon monoxide (CO). The requirement to perform a conformity determination ensures that federal approval and funding are awarded to transportation activities that are consistent with air quality goals. The air quality conformity analysis demonstrates that the Destination 2040 LRTP meets the Clean Air Act and Transportation Conformity Rule requirements for the 1997 ozone National Ambient Air Quality Standard (NAAQS) and the CO NAAQS, and that the LRTP has been prepared following all guidelines and requirements of these rules during this period. The analysis also shows that the implementation of the Boston Region MPO’s LRTP is consistent with the air quality goals of the Massachusetts State Implementation Plan and in conformity with that plan.

The second air quality analysis estimated greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions for projects in the LRTP and TIP as mandated by state legislation. The legislation requires reductions in GHG emissions of 25 percent below 1990 levels by 2020, and 80 percent below 1990 levels by 2050. To do so, state policies require the transportation sector to promote healthy transportation modes and support smart growth development.

The Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT) provided the MPO with statewide estimates of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions (the most prominent GHG) derived from the statewide travel demand model. These estimates were based on the collective list of recommended projects in all Massachusetts LRTPs and supplemented by “off-model” calculations of CO2 emissions reductions for smaller projects supplied by the MPOs. Collectively all the projects programmed in the MPOs’ LRTPs in the 2020 Action scenario (a build scenario) provide a statewide reduction of CO2 compared to the 2020 baseline case (a no-build scenario). The 2040 Action scenario also estimates a statewide reduction of CO2 emissions compared to the 2040 baseline case.

These results demonstrate that the transportation sector is expected to make positive progress toward meeting the GHG emissions reduction targets and complying with the requirements of the Global Warming Solutions Act. MassDOT and the MPOs will continue to advocate for steps needed to accomplish the Commonwealth’s long-term goals for GHG reductions.

Destination 2040 continues the MPO’s practice of funding operations-and-management-type projects that support bicycle, pedestrian, and transit projects, along with major roadway improvements. The MPO expects that continuing along this course will help to achieve its transportation vision for the future, improve the quality of life for Boston region residents, and enhance the environment in the whole region.

With the adoption of Charting Progress to 2040, the Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization’s (MPO) previous Long-Range Transportation Plan (LRTP), the MPO began charting a new course. Residents, municipalities, public agencies, and organizations from around the region helped the MPO decide how to invest its resources to improve transportation in the region. The result was an LRTP that represented a turning point in the philosophy and practice of the MPO. More explicitly than it had done in past, the MPO prioritized investments in smaller operations and management (O&M) projects that support transit, pedestrian, and bicycle modes, moving away from larger roadway projects. This new course meant that more than half of the projects programmed by the MPO, since Charting Progress to 2040 was adopted in 2015,were these types of O&M projects.

This new LRTP, Destination 2040, continues and strengthens this course. The LRTP represents the continued interest by the people in the region to develop a multimodal transportation system that serves all people in the region. While any forecast into the future is uncertain, the transportation system that Destination 2040 envisions is one that can address burgeoning transportation needs today, and that can adapt to those in the future. The vision of Destination 2040 is as follows:

The Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization envisions a modern, well-maintained transportation system that supports a sustainable, healthy, livable, and economically vibrant region. To achieve this vision, the transportation system must be safe and resilient; incorporate emerging technologies; and provide equitable access, excellent mobility, and varied transportation options.

In order to create a plan designed to implement this vision, the LRTP defines goals and objectives that guide the planning process and establishes performance measures to evaluate progress. It also outlines the transportation needs and challenges the region faces over the next 20 years. Finally, it identifies strategies to address those needs, using financial resources available to the Boston Region MPO.

Destination 2040 is a product of the Boston Region MPO, which is the designated MPO for the Boston metropolitan area. Each metropolitan area in the United States with a population of 50,000 people or more is required by federal legislation to establish an MPO. MPOs are responsible for providing a forum for a regional transportation planning decision-making process. The MPO body decides how to spend federal transportation funds for capital projects and planning studies for the area. The process is guided by a broad coalition of people including elected officials, municipal planners and engineers, transportation advocates, and interested residents.

The LRTP is one of the MPO’s required planning documents. It is meant to plan for the long-range future (at least 20 years) of the region. Every four years, the MPO identifies the system’s strengths and weaknesses; forecasts changes in population, employment, and land use; and creates a plan to address existing and future mobility needs. The resulting LRTP allocates funding for major projects in the Boston region and guides the MPO’s funding of capital investment programs and studies.

The federal government regulates the funding, planning, and operation of the surface transportation system through the federal transportation program, which was enacted into law through Titles 23 and 49 of the United States Code. Section 134 of Title 23 of the Federal Aid Highway Act and Section 5303 of the Federal Transit Act, as amended, require that urbanized areas conduct a transportation planning process, resulting in plans and programs consistent with the objectives of the metropolitan area, in order to be eligible for federal funds.

The most recent reauthorization of the surface transportation law is the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act. The FAST Act sets policies related to metropolitan transportation planning. The law requires all MPOs to carry out a continuing, comprehensive, and cooperative (3C) transportation planning process.

The Boston Region MPO is responsible for carrying out the 3C planning process in the Boston region and has established the following objectives for the process:

More information about the federal, state, and regional guidance governing the transportation planning process and the regulatory framework in which the MPO operates can be found in Appendix A of the LRTP Needs Assessment document.

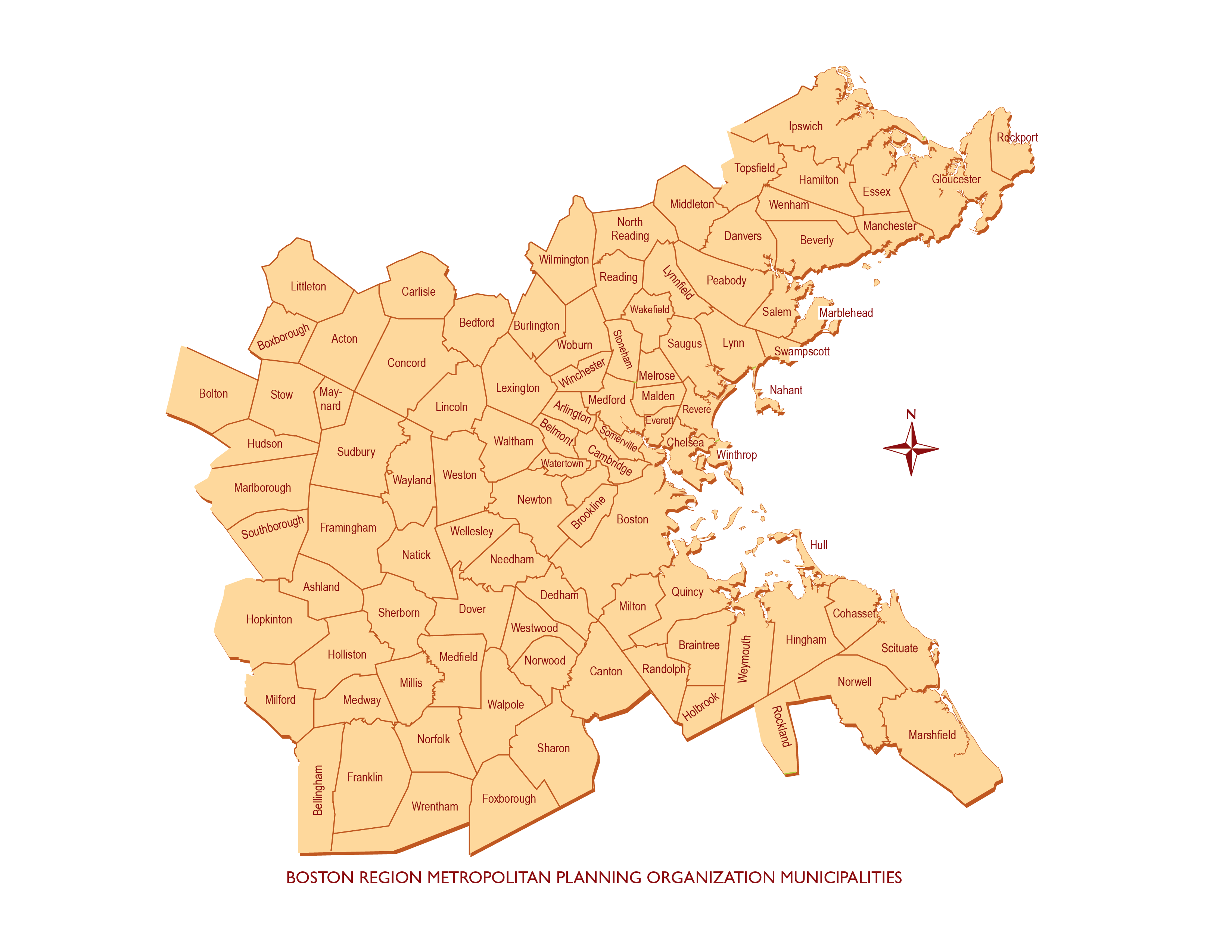

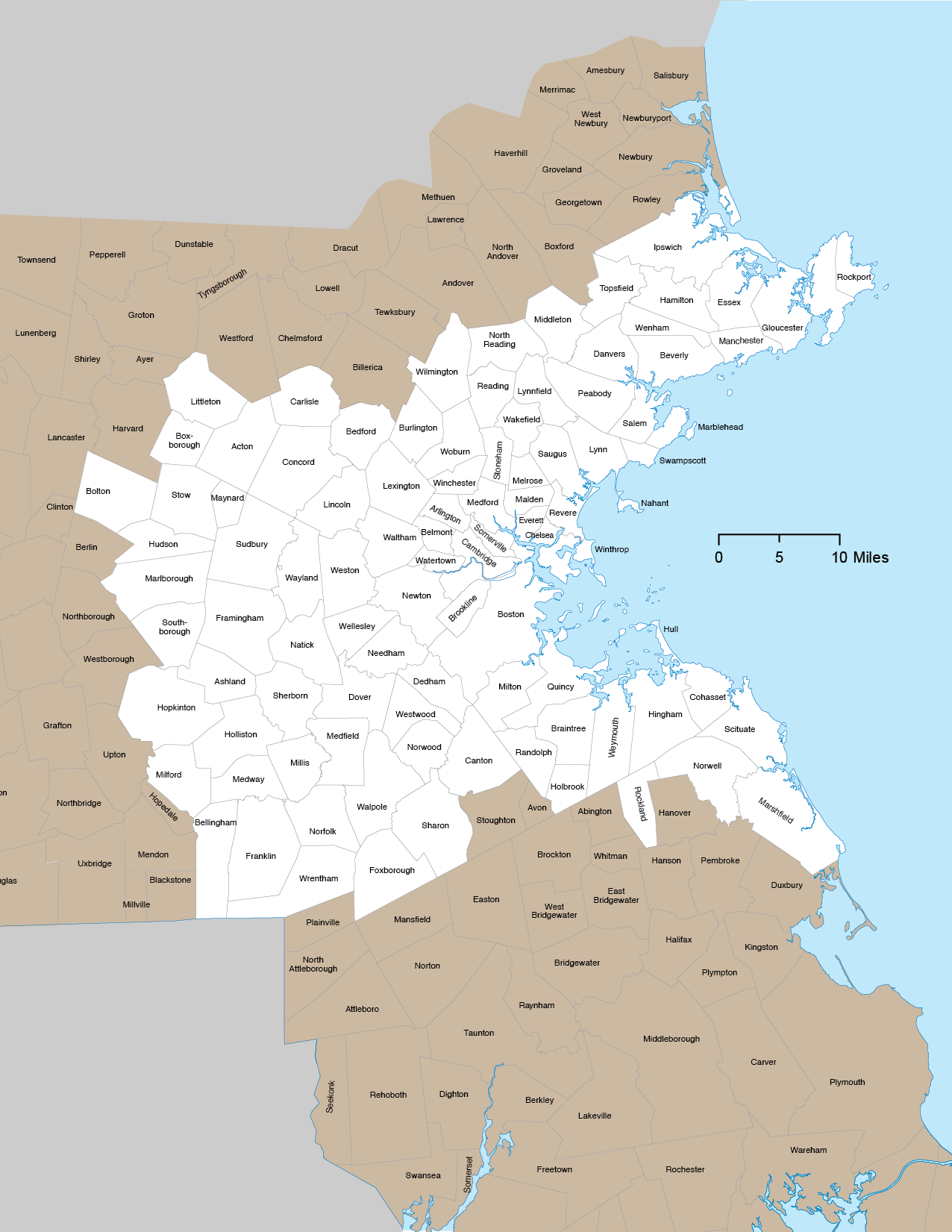

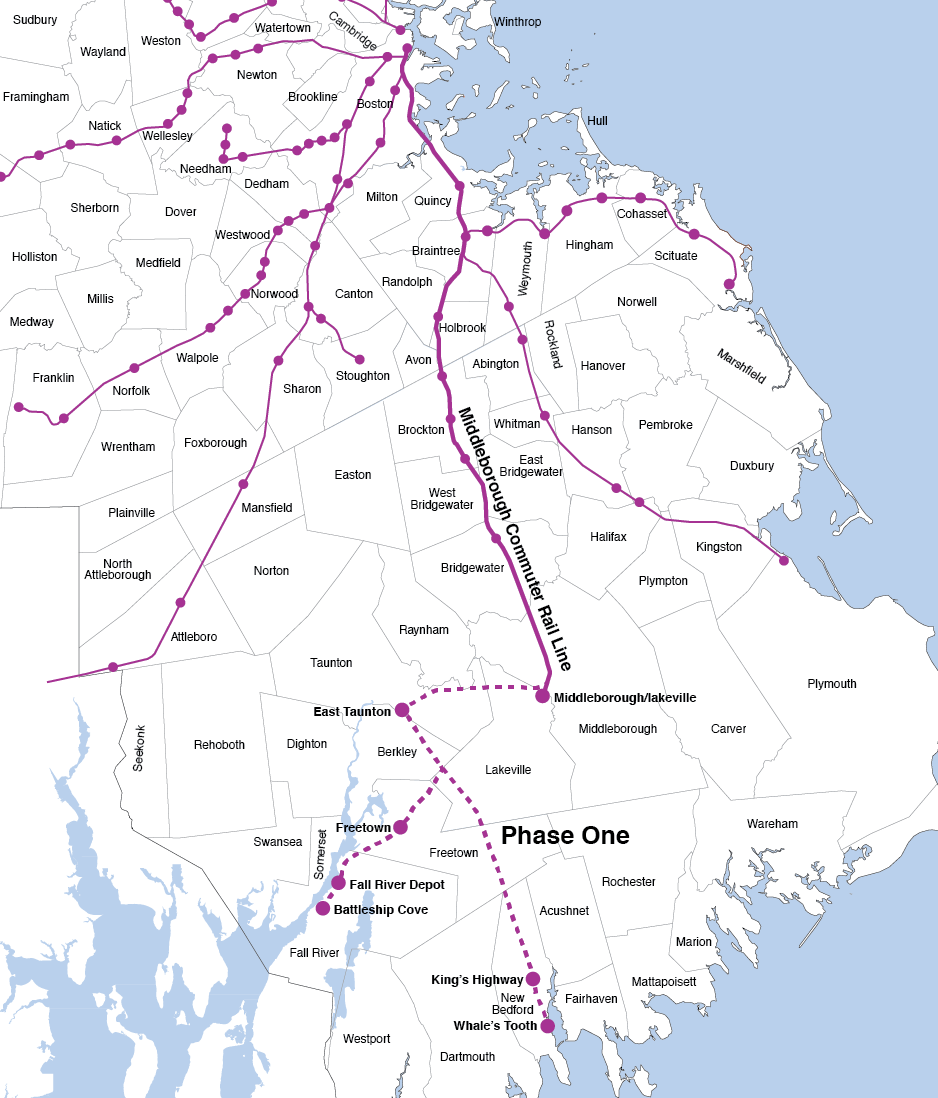

The MPO’s planning area covers 97 municipalities from Boston north to Ipswich, south to Marshfield, and west to Interstate 495. Figure 1-1 shows the map of the Boston Region MPO’s member municipalities.

Figure 1-1

Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization Municipalities

Source: Boston Region MPO.

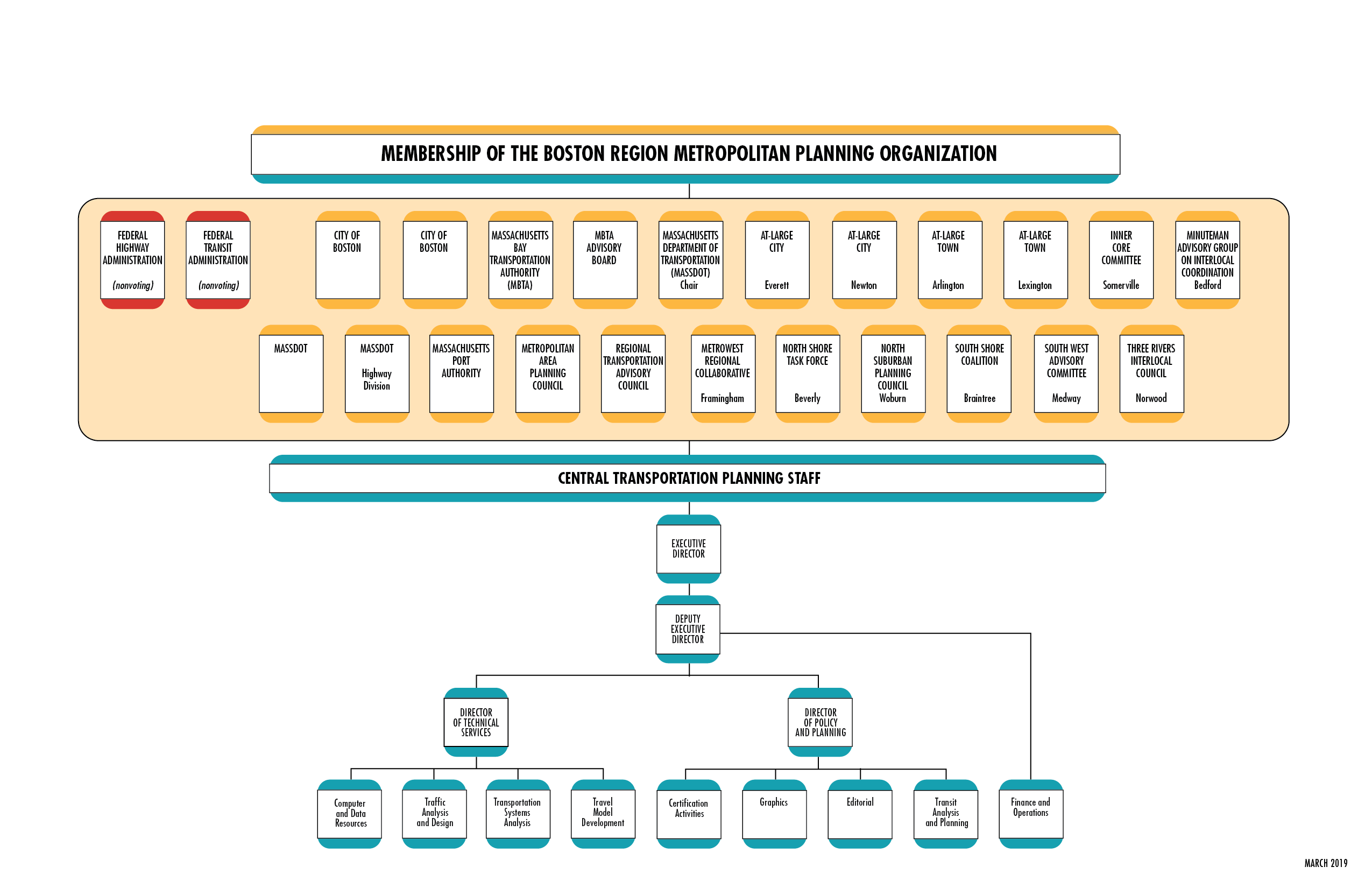

The MPO’s board comprises of 22 voting members. Several state agencies, regional organizations, and the City of Boston are permanent voting members, while 12 municipalities are elected as voting members for three-year terms. Eight municipal members represent each of the eight subregions of the Boston region, and there are four at-large municipal seats. The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and Federal Transit Administration (FTA) participate on the MPO board as advisory (nonvoting) members. Figure 1-2 shows MPO membership and the organization of the Central Transportation Planning Staff (CTPS), which serves as staff to the MPO.

Figure 1-2

Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization Member Structure

Source: Boston Region MPO.

As part of the 3C process, the Boston Region MPO regularly produces several planning and programming documents that describe MPO priorities and investments. These are collectively referred to as certification documents and are required for the MPO’s process to be certified as meeting federal requirements and, subsequently, to receive federal transportation funds. The three documents that comprise the certification documents are the LRTP, the Transportation Improvement Program (TIP), and the Unified Planning Work Program (UPWP). In addition to producing these documents, the MPO must also establish and conduct an inclusive public participation process; comply with all federal Title VI, environmental justice, and nondiscrimination requirements; and maintain transportation models and data resources to support air quality conformity determination and long- and short-range planning work and initiatives.

The following is a summary of each of the certification documents.

Several agencies are involved in planning and programming highway and public transit projects in the Boston region. The MPO regularly coordinates with these agencies, including MassDOT, the MBTA, and the region’s regional transit authorities (RTAs). Coordination ensures that agencies’ strategic visions complementary and comprehensively cover the various transportation needs in the region. In particular, MassDOT’s Capital Investment Plan (CIP), which includes MBTA capital projects as well as RTA investments, prioritizes funding according to MassDOT’s strategic goals. In addition, MBTA’s long-term investment plan, Focus40, describes the long-term vision and goals of the MBTA, guiding it toward a transportation system that is reliable, robust, and resilient. Destination 2040 represents the MPO’s continued collaboration with these agencies, as well as the region’s municipalities, other transit providers, and other stakeholders, to further a shared vision of a sustainable, equitable, accessible, and economically vibrant region.

This section describes how the MPO created and will implement Destination 2040. It discusses how the MPO identified transportation needs in the region through public outreach and data analysis; revisited and revised its investment programs and program sizes; established the financial resources available for funding projects and programs; selected projects for programming; developed the recommended plan; analyzed potential air quality and transportation equity impacts; collected public comments; and explained how the LRTP will monitor and implement the plan.

The process for developing Destination 2040 began with the development of the Needs Assessment. The Needs Assessment process consisted of two core components—conducting public outreach to gather input on transportation needs from people across the region, and analyzing data on transportation services and infrastructure to identify existing gaps and opportunities for improvement. In addition, MPO staff reviewed existing transportation plans and policies developed by municipalities and other transportation agencies to get a better understanding of their transportation needs. As new data became available, MPO staff updated relevant analyses as needed. The results of the Needs Assessment were used to revise the LRTP’s vision, goals, and objectives, select projects and programs to address the transportation needs in the region, and to develop future study ideas as part of the UPWP.

For the public outreach component of the Needs Assessment, conducted from fall of 2017 to summer of 2018, the MPO received more than 2,000 comments and ideas about transportation needs and opportunities for improving the transportation system. These comments were gathered through various formats, summarized below:

To identify transportation needs in the future, it is necessary to project the land use patterns, growth in employment and population, and trends in travel patterns to determine how they affect demand on the region’s transportation system. MAPC, the region’s land use planning agency, was responsible for preparing detailed population, employment, and household projections to the year 2040 to support the LRTP. MassDOT helped lead this process by creating a projections committee with members from each of the state’s MPOs, MAPC, CTPS, and other relevant government agencies. This committee oversaw the development of regional population, labor force, household, and employment projections for each MPO in the state. MAPC and the University of Massachusetts Donahue Institute were contracted as technical leads for the production of these projections.

Overall, the land use scenario created for the LRTP, Destination 2040, involves key assumptions about the future and reflects large-scale, long-term land use trends in the region due to an aging population, a restructured economy, and the investment in development projects already planned. Detailed information on this process can be found in Chapter 2 of the Needs Assessment document.

In the fall of 2018 and the winter of 2019, using the Needs Assessment results, the MPO revisited its vision statement and supporting goals and objectives to ensure that they fully addressed the region’s transportation needs. The vision statement and supporting goals and objectives were found to reflect the overarching needs identified in the Needs Assessment and from public input. The goals largely remained the same as in Charting Progress to 2040, while several of the objectives have been revised to better reflect the results of the Needs Assessment, to better align the objectives with the roles and responsibilities of the MPO, and to incorporate new planning requirements. MPO staff also received input from the public on the draft revisions to the vision, goals, and objectives in winter 2019 through an online survey.

In addition to addressing the identified needs, the MPO’s goals and objectives relate to the 10 federal planning factors that are included in the FAST Act. More information on the relationship between the MPO’s goals and objectives and the federal planning factors can be found in Appendix A of the Needs Assessment document. The MPO’s revised vision, goals, and objectives are shown in Figure 1-3.

Figure 1-3

Destination 2040 Vision, Goals, and Objectives

Source: Boston Region MPO.

Together, the vision, goals, and objectives, lay the groundwork for the MPO’s performance-based planning practices, which in turn informs all of the work conducted by the MPO, including evaluating and selecting projects for the LRTP and TIP and selecting studies for the UPWP.

The finance plan is an important part of the LRTP, which is required to be a financially constrained document—meaning that the Boston Region MPO has the finances to cover the projects and programs recommended in the plan. The financial assumptions for this LRTP include an increase in federal highway funding for the MPO compared to the previous LRTP. Charting Progress to 2040, (the MPOs 2015 LRTP), allowed for an increase in revenue of one-and-a-half percent per year. For this LRTP, the MPO assumed an increase in federal highway dollars of two-and-two-tenths percent per year, based on guidance from MassDOT, which was developed in consultation with federal agencies. Therefore, the MPO has additional resources for commitments to projects included in Destination 2040. Project cost increases, due to the application of an inflationary factor (four percent per year), also affect funding in the later time bands of the LRTP. Transit finances vary by funding source. Chapter 3 provides detailed information about finances for Destination 2040.

To initiate the project selection process, MPO staff identified possible projects and programs for funding and assembled them into the Universe of Projects and Programs. The full Universe of Projects and Programs is included in Appendix A. All active and conceptual highway and transit projects that are eligible for inclusion in the LRTP were included in the Universe of Projects. This includes all projects that cost more than $20 million and/or would add capacity to the transportation network. Specifically, the Universe of Projects includes projects that

The Universe of Programs list consists of those investment programs that were considered for inclusion in the LRTP. Investment programs include projects that do not have to be listed in the plan because they cost less than $20 million and do not add capacity to the system. These programs include those in Charting Progress to 2040 as well as proposed new and revised programs that emerged from the results of the Needs Assessment.

The MPO also received public input through a survey about its recommended priority projects and programs in the Universe of Projects and Programs lists. Based on public input and discussions with the MPO board, this LRTP includes the following investment programs:

These programs are designed to prioritize the types of transportation projects that the MPO funds through the TIP. Any project under consideration must fit into one of the programs. In this LRTP, the MPO kept the five investment programs in Charting Progress to 2040, and added one program, Transit Modernization. The Complete Streets Program was expanded to include dedicated bus lanes and climate resiliency improvements, while the Community Connections Program was expanded to include investments that connect elderly adults to transportation.

In the spring of 2019, the MPO set aside a specific amount of funding for each investment program based on the investment program decisions. The funding amounts generally correspond to the levels that the programs have been funded in the past five TIPs. Notably, the amount set aside for the Complete Streets Program was not only expanded (because the MPO is funding more of these types of projects), it was increased by an additional two percent to accommodate dedicated bus lane projects. The estimate for dedicated bus lanes was based on funding several of the highest priority bus corridors identified in a previous MPO study and cost estimates provided by the MBTA. The MPO then allocated funding for the six programs across the LRTP’s four bands (FFYs 2020–24, 2025–29, 2030–34, and 2035–40). Based on this allocation, the MPO distributed the following funding amounts to these investment programs:

Major Infrastructure (projects that add capacity to the transportation network): as much as30 percent

Complete Streets: 45 percent

Intersection Improvements: 13 percent

Bicycle Network and Pedestrian Connections: 5 percent

Community Connections: 2 percent

Transit Modernization: 5 percent

The MPO applied its goals and objectives as criteria in a qualitative evaluation of the major infrastructure and capacity-adding highway projects in the Universe of Projects. Only those projects that had been sufficiently well-defined to allow for analysis were evaluated. The assessment of how well projects would address the MPO’s goals and objectives helped the MPO identify priority projects for the Major Infrastructure Program. Appendix B provides detailed information on project evaluations and documentation of the evaluation process.

In the winter of 2019, MPO staff reached out to municipalities and MassDOT highway districts to gather information about the readiness of highway projects in the Universe of Projects list and the action being taken to advance the projects. Using this information, along with the project evaluations, MPO staff developed several possible funding alternatives that reflected the investment program funding goals. These alternatives include the following:

The MPO board reviewed and discussed the alternatives in May 2019 and voted to adopt Alternative 4 as its preferred alternative for the Destination 2040 LRTP. This will allow funding for projects that may emerge in the future and funding for projects whose costs may increase after proceeding to final design. More detail on the project selection process is included in Chapter 4.

Once the projects were selected, MPO staff conducted two analyses to assess how the projects may affect minority and low-income populations in the outer year of the LRTP (2040). These analyses include identifying potential future disparate impacts and disproportionate burdens (DI/DB) that may result from the program of projects, and mapping the program of projects overlaid on areas with high shares of minority and/or low-income populations.1-2 These analyses are required by the Title VI and environmental justice guidance promulgated by the FTA and/or the FHWA. The results of the analysis and the methodology can be found in Chapter 6. The draft DI/DB Policy used to complete the DI/DB analysis can be found in Appendix C.

Additional analyses were also conducted to assess the air quality and greenhouse gas impacts of the projects selected for the LRTP. The first analysis ensures that the LRTP is consistent with the Commonwealth’s plans for attaining and maintaining air quality standards. The second analysis reports the results of the carbon dioxide emissions associated with the projects and programs being included in the LRTP, as required by the Massachusetts Global Warming Solutions Act. The results of the analysis and the methodology can be found in Chapter 7.

The public was consulted throughout the entire development of the LRTP. The Needs Assessment, the revised vision, goals, and objectives, the investment programs, and the recommended plan reflect public input during each stage of LRTP development. The LRTP’s public comment period in July and August 2019 provides the public a final opportunity to review and comment on the recommended plan and the entire LRTP development process before Destination 2040 is finalized. To facilitate this, MPO staff visited several transportation events in the region to encourage public comment. The public was notified of the availability of the draft LRTP on the MPO’s website, sent out via email, posted on Twitter, and posted on the MPO's blog. More details on the public input process can be found in Appendix D.

In recent years, the MPO has been incorporating performance-based planning and programming (PBPP) practices into its LRTP development and other processes. These practices are designed to help direct MPO funds towards achieving specific outcomes for the transportation system. The MPO’s goals and investment programs are key components of its PBPP framework. In FFY 2018, the MPO began to set targets for specific performance measures. Over time, the MPO will closely link its performance targets, investment decisions, and monitoring and evaluation activities. More details on the PBPP process can be found in Chapter 5.

As the guiding document for the MPO’s investment priorities, each LRTP is subsequently implemented through the TIP and the UPWP. Specifically, the needs identified in the Needs Assessment and the goals and objectives established in the LRTP are used to guide the programming of studies and projects in each year’s TIP and UPWP. The transportation needs identified in the Needs Assessment often serve as the catalyst for developing studies programmed in the UPWP. Additionally, the projects programmed in the investment programsare defined each year in the TIP. The objectives described in the LRTP will also be used to develop new evaluation criteria for TIP projects starting with the FFY 2021–25 TIP. More details on the process of implementing the LRTP can be found in Chapter 8.

The remaining chapters of Destination 2040 are organized as follows:

Chapter 2—Transportation Needs in the Region: Includes a summary of the regional transportation needs identified in the Needs Assessment

Chapter 3—Funding the Transportation Network: Describes the transportation funding to be spent in the MPO region over the life of the LRTP; explains LRTP fiscal constraint requirements; and identifies the amount of transportation funding over which the MPO has decision-making power

Chapter 4—The Recommended Plan: Describes the projects and programs in the LRTP and the process for their selection

Chapter 5—System Performance Report: Discusses federal requirements for performance measurement, the MPO’s development and implementation of a PBPP process, the MPO's performance targets, and the region’s current performance with respect to federally required performance measures

Chapter 6—Transportation Equity Performance Report: Includes a description of the MPO’s approach to identifying transportation equity populations and their role in Title VI analysis, and presents the Title VI and environmental justice analyses required for the LRTP

Chapter 7—Air Quality Conformity Determination and Greenhouse Gas Analysis: Includes the air quality conformity determination showing that the LRTP is consistent with the Commonwealth’s plans for attaining and maintaining air quality standards; and reports on the carbon dioxide emission reductions from projects and programs in the LRTP in accordance with the Massachusetts Global Warming Solutions Act

Chapter 8—Next Steps: Implementation of Destination 2040: Describes the activities the MPO will undertake to implement the LRTP, including through its TIP and UPWP

Appendices: Provide more detail on specific components of the LRTP development process, and includes:

A critical early step in developing the Long-Range Transportation Plan (LRTP) was to gather, organize, and analyze available sources of data about the regional transportation system and its present and future needs. This process resulted in the Needs Assessment, which consists of two main parts:

Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) staff used the Needs Assessment application to analyze various components of the transportation system and their capacity, condition, and current and projected use.

The Needs Assessment analysis guided the MPO when deciding how to address the region’s transportation needs through this LRTP, and it also will guide future decision making about projects to fund in the MPO’s Transportation Improvement Program (TIP) and studies to conduct through the Unified Planning Work Program (UPWP). The Needs Assessment also includes baseline information for the MPO’s performance-based planning and programming (PBPP) process, which tracks progress over time to determine whether planned changes to the transportation system are helping to achieve the MPO’s goals and objectives.

This chapter presents a summary of the region’s needs (described in full in the associated Needs Assessment document). Both the Needs Assessment document and the interactive Needs Assessment application may be accessed through the MPO’s website at https://www.bostonmpo.org/maploc/www/apps/lrtpNeedsAssessmentApp/index.html.

Information in this chapter and the online Needs Assessment document is organized according to the goals outlined in this LRTP, which the MPO staff used to evaluate projects and programs considered for programming in this LRTP. The goals are focused on the following topics:

The online Needs Assessment document includes the following chapters, which contain details about the needs, as well as the conditions that create the needs.

The Needs Assessment incorporates information from previous and ongoing transportation planning work, including the Charting Progress 2040 LRTP (the MPO’s previous LRTP updated in 2016), PBPP work being conducted by the MPO, the MPO’s Congestion Management Process, transportation equity and public outreach, MPO studies, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority’s (MBTA) Focus40 plan, and relevant studies conducted by other transportation agencies.

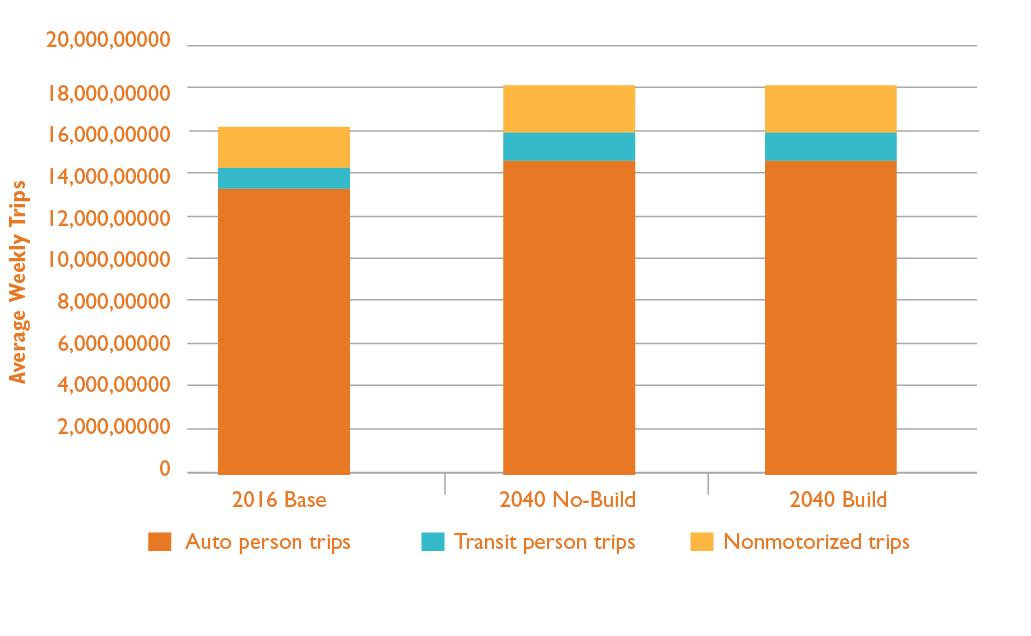

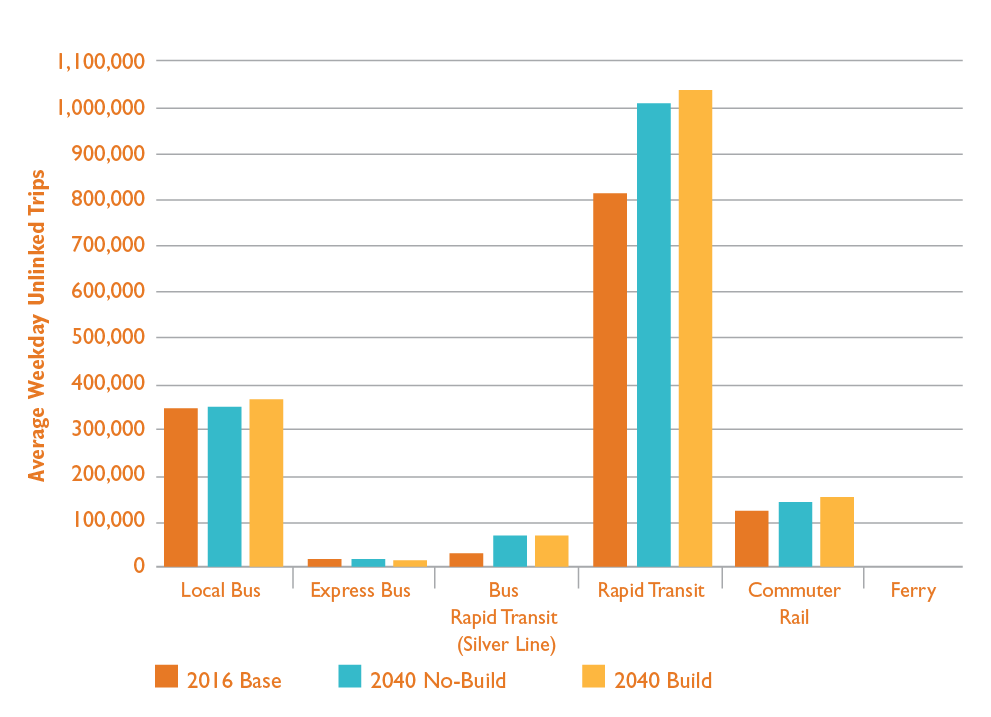

Travel demand modeling is a key part of the LRTP and Needs Assessment analyses. The Destination 2040 LRTP uses a base year of 2016 and a future year of 2040 to model the transportation network and socioeconomic trends. Inputs into the travel demand model included existing and projected socioeconomic information (population, housing, and employment data) and the existing and proposed transportation network. These existing and projected data were important factors in determining regional transportation needs.

For each of the MPO’s six goal areas, the sections below provide the issue statement, the summary of needs, and the recommendations to address those needs for the next 20 years. A description of the types of recommendations presented in the tables includes the following:

Detailed information may be found in Chapters 4 through 9 of the full Needs Assessment report, which includes the following:

People who travel by car, truck, bus, rail, bicycle, or on foot in the Boston region seek to travel safely, but often these modes compete for space and priority on the roadways. While roadway crashes overall have declined over time, recent increases in bicycle and pedestrian crashes and in serious injuries to pedestrians attest to the challenge of ensuring safety for all modes. Changes to travel patterns, caused in part by increased use of transportation network company (TNC) services (for example, Uber and Lyft) and deliveries from online retail businesses, add to the many factors that affect safety on the region’s transportation system. Meanwhile, advancements in connected and autonomous vehicle (CAV) technology have the potential to generate safety benefits, but this technology may also change travel patterns and influence traveler behavior in ways that introduce new concerns.

Reducing the number of transportation-related crashes, safety incidents, injuries, and fatalities as well as related property damage, pain, and suffering, is the Boston Region MPO’s highest priority. This focus is in line with federal and Commonwealth of Massachusetts goals and Vision Zero policies that are being implemented by municipalities in the region. (More information is available in Chapter 5–System Performance Report.) Potential projects that improve transportation safety in the region will need to account for all modes and employ a variety of strategies. Effective solutions will also require collaboration between the MPO, the Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT), other Commonwealth executive agencies, the region’s transit providers, municipalities, and other stakeholders.

Over the last several decades, the MPO has built a practice of analyzing roadway crash trends and crash locations. The MPO helps address key safety issues by recommending roadway design solutions for specific locations; creating tools and guidance to help municipalities address local safety issues; and investing in capital projects through the LRTP and TIP to improve safety.

Going forward, the MPO must continue to enhance practices of analyzing data, collecting public feedback, and applying staff expertise to recommend safety solutions. The MPO must also continue to apply and improve LRTP and TIP evaluation and development processes that help identify and support projects likely to have safety benefits. The MPO should also continue to monitor the potential impacts that CAV technology will have on roadway user behavior and safety.

There are also areas where the MPO can expand activities to address transportation safety. The MPO will need to consider transit safety issues, data requirements, and needs when coordinating with the region’s transit providers to set targets for federally required transit safety performance measures. (More information is available in Chapter 5–System Performance Report.) The MPO should analyze transit safety trends on an ongoing basis, consider the potential safety benefits of projects for the MBTA, Cape Ann Transportation Authority (CATA), MetroWest Regional Transit Authority (MWRTA), and MassDOT that are programmed in the TIP, and explore opportunities to support transit agencies’ safety initiatives and investments. The MPO should also continue to collaborate with safety practitioners, transportation agency representatives, municipalities, and others to identify both infrastructure and non-infrastructure approaches (such as education and awareness campaigns) to reduce fatalities, injuries, incidents, and other safety outcomes across all transportation modes and systems.

Table 2-1 summarizes key findings about safety needs that MPO staff identified through data analysis and public input. It also includes staff recommendations for addressing each need.

Table 2-1

Safety Needs in the Boston Region Identified through Data Analysis and Public Outreach and Recommendations to Address Needs

| Emphasis Area |

Issue |

Needs |

Recommendations to Address Needs |

|---|---|---|---|

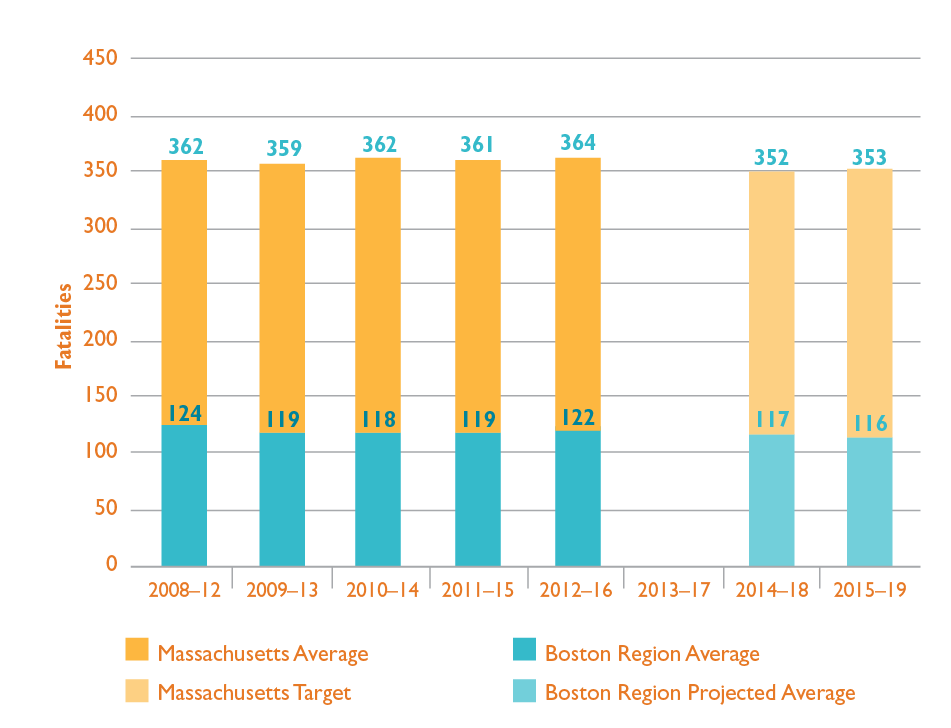

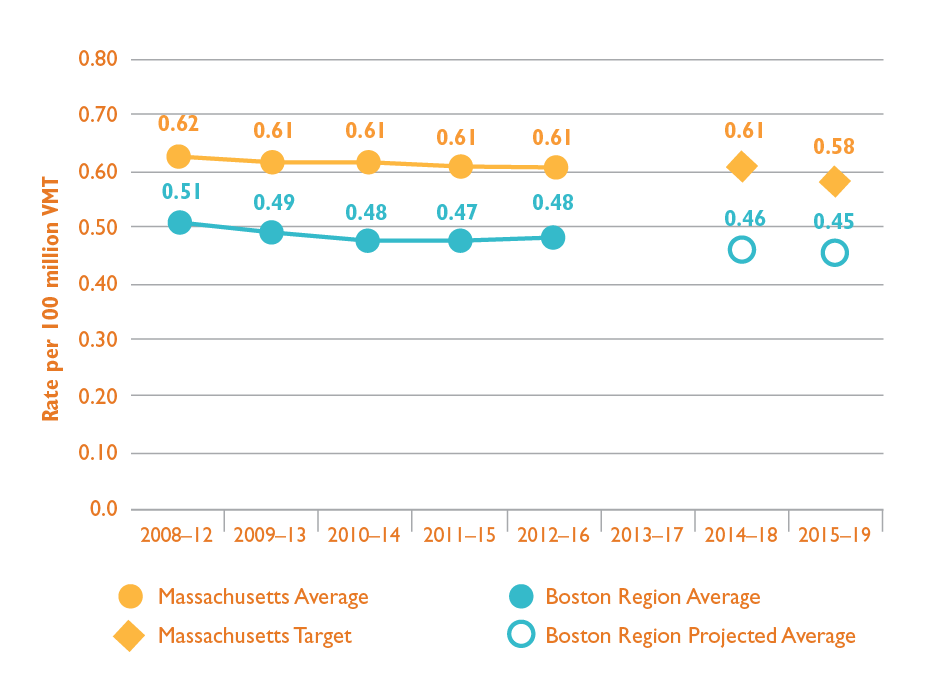

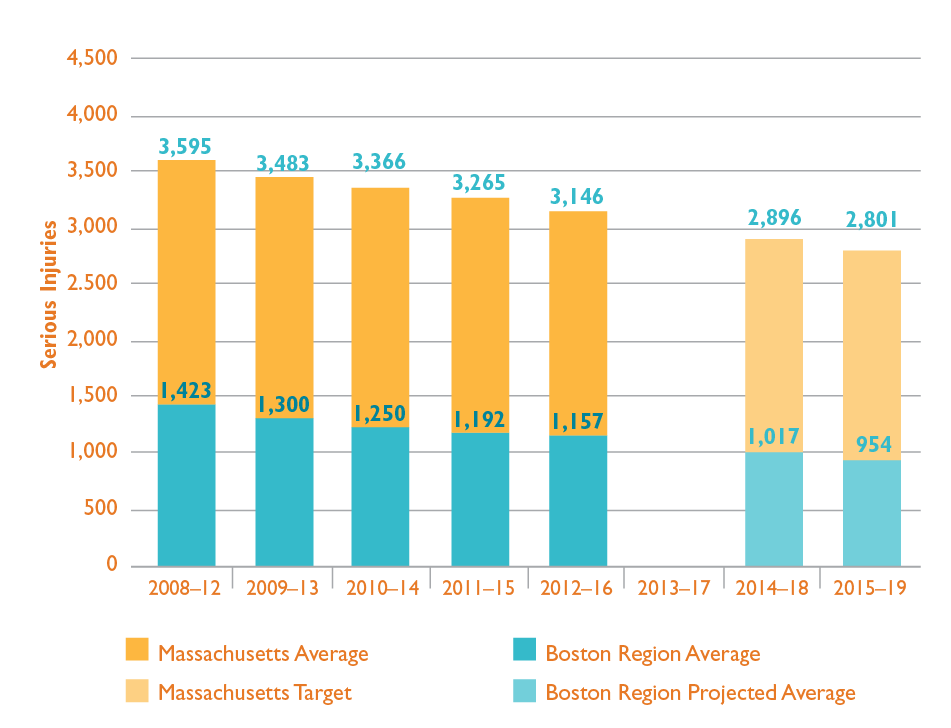

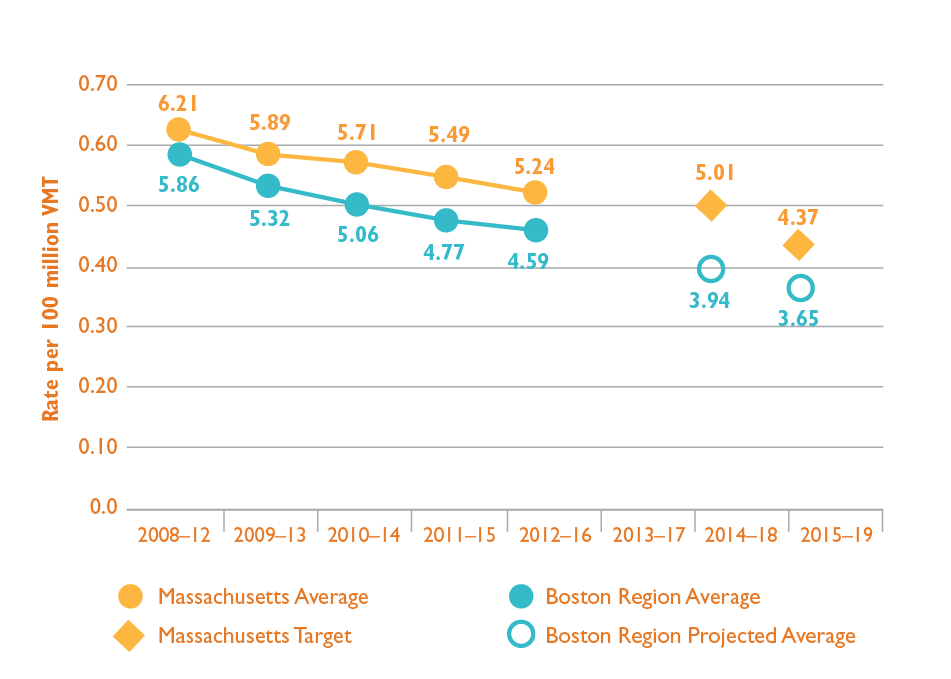

Fatalities and serious injuries from roadway crashes |

Average number of fatalities and serious injuries from roadway crashes have declined over the past five years. However, a multi-strategy approach will be needed to eliminate roadway crash fatalities and injuries in the Boston region. |

Identify crash factors and countermeasures. Consider capital investment, education, enforcement, and other approaches to improve roadway safety. |

Existing Initiatives Coordinate with partner agencies to collect data that supports safety research and analysis Participate in road safety audits for roadway improvement projects Continue to collect and analyze safety data and monitor performance measures Existing Study Conduct TIP before-after studies to evaluate safety impacts of funded projects Proposed Study Study factors that may contribute to fatal and serious injury crashes on the region’s roadways Proposed Initiatives Publicize transportation safety-oriented education and awareness material through the MPO’s communication and public involvement channels Coordinate with other agencies and stakeholders on their approaches for addressing education, enforcement, and other factors that influence safety |

High crash locations |

The number of all crashes should be reduced. Crash cluster locations with high EPDO values indicate locations with high crash frequencies and/or where crashes are severe. |

Address the region’s top-ranking crash cluster locations. Address MassDOT-identified Top 200 high crash intersections in the Boston region (66 total), such as those on Route 9 in Framingham, Route 107 in Lynn and Salem, and Route 16 in Chelsea, Everett, and Medford. |

Existing Programs Intersection Improvements Complete Streets Major Infrastructure investment program Existing Studies Recommend solutions for specific locations through the Community Transportation Technical Assistance, Addressing LRTP Priority Corridors, Addressing Subregional Priority Roadways, and Low-Cost Solutions for Express Highway Bottlenecks studies Recommend solutions for specific locations through Safety and Operations at Selected Intersections studies New Initiative Publicize transportation safety-oriented education and awareness material through the MPO’s communication and public involvement channels |

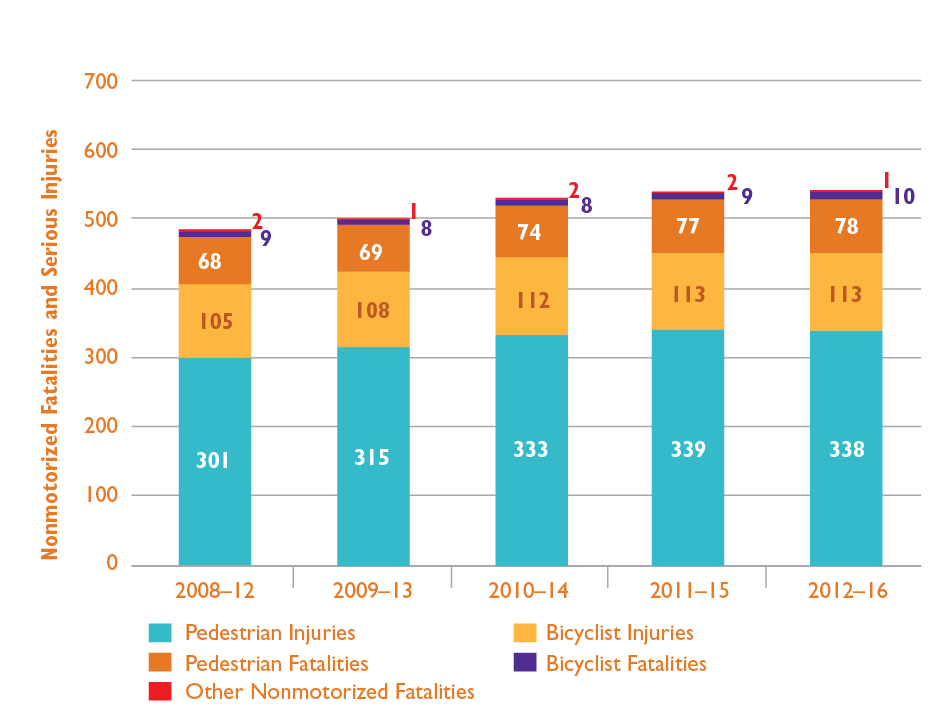

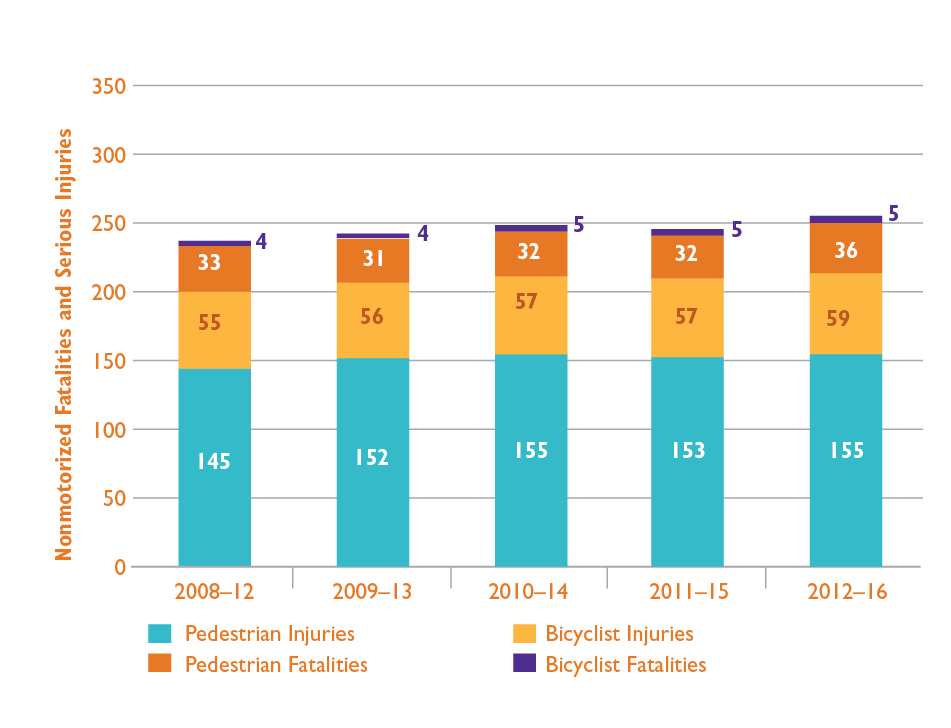

Pedestrians |

In the Boston region, the number of pedestrian-involved crashes is increasing. Pedestrians were involved in a disproportionate share of roadway crashes resulting in fatalities (29 percent) and serious injuries (13 percent), based on 2012–16 rolling annual averages. Pedestrian safety was a top concern mentioned during the MPO’s outreach events. |

Address top-ranking pedestrian crash cluster locations, including those in downtown areas in Chelsea, Lynn, Quincy, Boston, and Framingham. Provide well-maintained, connected sidewalk networks. Improve pedestrian connections at intersections. Develop separated shared-use paths. |

Existing Program Intersection Improvements Complete Streets Bicycle and Pedestrian programs Existing Studies Recommend solutions for specific locations through Community Transportation Technical Assistance, Addressing LRTP Priority Corridors, Addressing Subregional Priority Roadways studies Use the MPO’s Pedestrian Report Card Assessment tool to analyze pedestrian safety and walkability Recommend solutions for locations with high pedestrian crash rates or pedestrian fatalities or injuries Proposed Study Recommend safety solutions for people traveling to transit stops or stations |

Bicyclists |

In the Boston region, bicyclists account for a disproportionate share of roadway crash fatalities (four percent) and serious injuries (five percent) based on a 2012–16 rolling annual average. Bicycle safety was a top concern mentioned during the MPO’s public outreach events. |

Address top-ranking bicycle crash cluster locations, including those in Boston, Cambridge, and Somerville. Develop separated shared-use paths and protected bike lanes. Develop a connected bicycle network. |

Existing Programs Intersection Improvements Complete Streets Bicycle and Pedestrian program Existing Studies Recommend solutions for specific locations through Community Transportation Technical Assistance, Addressing LRTP Priority Corridors, Addressing Subregional Priority Roadways studies Use the MPO’s Bicycle Report Card Assessment tool to analyze bicycle safety Recommend solutions for locations with high bicycle crash rates or bicycle fatalities or injuries |

Trucks |

Truck-involved crashes account for approximately six percent of total motor vehicle crashes in the Boston region; however truck and large vehicle crashes account for 12 percent of roadway fatalities according to a 2011–15 rolling annual average. |

Address top truck crash cluster locations. Modernize obsolete interchanges, such as the I-90 and I-95 interchange in Weston and the I-95 and Middlesex Turnpike interchange in Burlington. |

Existing Program Intersection Improvements Complete Streets Major Infrastructure investment program Proposed Program Fund projects to improve truck safety through an MPO Interchange Modernization investment programs Existing Study Recommend solutions for specific locations through Low-Cost Solutions for Express Highway Bottleneck studies |

Multimodal roadway usage |

Cars, trucks, buses, bicyclists, pedestrians, and others compete for space and travel priority in constrained roadway environments. Delivery vehicles transporting online purchases and TNC vehicles picking up or dropping off passengers also compete for curb space and create conflicts. Both of these factors can create unsafe conditions for travelers. |

Incorporate Complete Streets design and traffic calming principles in roadway projects. Identify strategies to manage roadway user priority, parking, and curb space. |

Proposed Initiative Consider curbside land use and demand and suggest management and improvement strategies when conducting MPO traffic engineering and freight studies |

Transit safety |

The MBTA reported recent increases in fatalities on its system, particularly on the commuter rail. The MBTA and the RTAs in the Boston region must continue to monitor and reduce bus collisions, derailments, and other accidents that may contribute to negative safety outcomes. |

Collect and analyze safety data, establish transit safety performance measures, set targets, and monitor the measures. Identify and invest in priority state-of-good-repair and modernization projects (e.g. positive train control and rapid transit vehicle upgrades). Coordinate with transit providers and partner agencies on safety education and awareness initiatives. |

Proposed Program Transit Modernization investment program

|

Connected and Autonomous Vehicles |

CAV technology is advancing. While CAV applications may reduce instances of human driver error, limiting factors such as inclement weather and device inoperability, may reduce their safety effectiveness. Riskier driver, pedestrian, and other roadway user behavior may offset safety benefits. |

Monitor advancements in CAV technology. Monitor and analyze safety impacts of CAV deployments, particularly in the Boston region. |

Proposed Study Research safety outcomes of autonomous vehicle testing in Boston or other metropolitan areas |

CAV = Connected and Autonomous Vehicles. EPDO = Equivalent Property Damage Only. FFY = federal fiscal year. LRTP = Long-Range Transportation Plan. MassDOT = Massachusetts Department of Transportation. MBTA = Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. MPO = Metropolitan Planning Organization. RTA = regional transit authority. TNC = transportation network company.

Source: Boston Region MPO.

The Boston region’s transportation infrastructure is aging and the demands on roadway and transit facilities have stressed the infrastructure to the point that routine maintenance is insufficient to keep up with necessary repairs. As a result, there is a significant backlog of projects required to maintain the transportation system and assets in a state of good repair, including projects that address bridges, roadway pavement, transit rolling stock and infrastructure, and traffic and transit control equipment. In addition, parts of the transportation system may be compromised if climate change trends continue as projected.

The transportation system must be brought into a state of good repair, maintained at that level, and enhanced to ensure mobility, efficient movement of goods, and protection from potential sea level rise and storm-induced flooding. Financial constraints require the Boston Region MPO, MassDOT, and the region’s transit agencies to set priorities, considering the most crucial maintenance needs and the most effective ways to program their funding. At the same time, infrastructure that could be affected by climate change must be made more resilient.

The MPO’s understanding of system preservation and modernization needs are informed by various planning processes conducted by transportation agencies in the region. MassDOT has developed a Transportation Asset Management Plan (TAMP), a risk-based asset management plan for bridge and pavement assets on the National Highway System (NHS) in Massachusetts, which will help MassDOT plan to improve NHS asset condition and performance. Similarly, the transit agencies in the Boston region—the MBTA, MWRTA, and CATA—have produced Transit Asset Management (TAM) plans, which will help them prioritize investments to maintain state of good repair in transit vehicles, facilities, and other infrastructure. These agencies, along with the MPO, monitor changes in asset condition over time using federal established performance measures for NHS bridges, pavement, and transit assets.

The MBTA’s Strategic Plan and 25-year investment plan,Focus40, complement the asset management plans by specifying state of good repair and modernization programs and projects, both for individual MBTA services and the system as a whole. Likewise, MassDOT’s annual Capital Investment Plan development process places top priority on investments that support transportation state of good repair and reliability. In addition, the report recently released by the Commission on the Future of Transportation in the Commonwealth,Choices for Stewardship: Recommendations to Meet the Transportation Future, includes recommendations to modernize existing state and municipal transit and transportation assets to more effectively and sustainably move more people throughout the Commonwealth and make transportation infrastructure resilient to a changing climate. MassDOT and the MBTA track performance over time both through annual reporting conducted by the Commonwealth’s Performance and Asset Management Advisory Council and through MassDOT’s Tracker.

To address identified needs, the MPO can invest its Regional Target dollars to and coordinate with its partners to support transportation infrastructure preservation and modernization. The MPO can use information from the aforementioned planning processes to consider and provide feedback on projects and programs that agencies bring forward for inclusion in the LRTP and TIP. The MPO may also choose to support some of these or other system preservation investments directly with its Regional Target funds. When spending its Regional Target funds, the MPO uses current system preservation-related TIP evaluation criteria to determine whether a project improves substandard pavement, bridges, sidewalks, signals or transit assets, or otherwise improves emergency response or the transportation system’s ability to respond to extreme conditions. The MPO may be able to use information from MassDOT and transit agency planning processes to supplement its existing project evaluation process.

Table 2-2 summarizes key findings regarding system preservation and modernization needs that MPO staff identified through data analysis and public input. It also includes staff recommendations for addressing each need.

Table 2-2

System Preservation and Modernization Needs in the Boston Region Identified through Data Analysis and Public Outreach and Recommendations to Address Needs

| Emphasis Area |

Issue |

Needs |

Recommendations to Address Needs |

|---|---|---|---|

Bridges |

Bridge condition: Currently, of the 2,811 bridges in the region 151 (five percent) are structurally deficient. Approximately 12 percent of the National Highway System (NHS) bridges in the Boston region are considered to be in poor condition. |

Meet MassDOT’s performance measure to prevent the number of structurally deficient bridges from exceeding 300 statewide.

Maximize the number of bridges in the region considered to be in good condition, and minimize the number of bridges considered to be on poor condition. |

Existing Programs Complete Streets Program Major Infrastructure Program Proposed Program Interchange Modernization Program

|

Bridges |

Bridge Health Index scores: Currently, as measured on this index, 33 percent of bridges in the region are in good condition, 35 percent are in poor condition, and 32 percent have not been rated because of missing data. |

Meet MassDOT’s performance measure to maintain a systemwide Bridge Health Index score of 92 (measured on a scale of zero to 100) in calendar year 2020 and a score of 95 in the long term. |

Existing Programs Complete Streets Program Major Infrastructure Program Proposed Program Interchange Modernization Program

|

Pavement Management |

Condition of MassDOT-maintained roadways: Of the roadways in the region maintained by MassDOT, 69 percent are in good condition, 25 percent are in fair condition, and six percent are in poor condition. This accounts for interstates and mix of NHS and non-NHS roadways. |

Monitor the MassDOT Pavement Management program (interstates and mix of NHS and non-NHS roadways). MassDOT-maintained arterial roadways make up 55 percent of monitored roadways, however 86 percent of the arterial roadways are in poor condition; lengthy arterials in poor condition are located in Arlington, Boston, Brookline, Cambridge, Chelsea, Lynn, Malden, Medford, Newton, and Salem. |

Existing Programs Intersection Improvement Program Complete Streets Program Major Infrastructure Program Proposed Program Interchange Modernization Program

|

Pedestrian Facilities |

Sidewalk location and condition: Of the sidewalks in the state, 81 percent are municipally owned. Neither the MPO nor MassDOT maintain pedestrian facility data. Knowing where sidewalks are located or absent, and their condition, is a key element in planning. |

Identify the location of sidewalks and their condition; identify those around transit stations. |

Existing Programs Bicycle Network and Pedestrian Connections Program Study issues through the Bicycle and Pedestrian Support Activities program (UPWP) Existing Studies Addressing Priority Corridors from the LRTP Needs Assessment (FFY 2019 UPWP) Addressing Safety, Mobility, and Access on Subregional Priority Roadways (FFY 2019 UPWP) Proposed Study Regionwide Sidewalk Inventory |

Transit Asset State of Good Repair |

State of good repair for the transit system: The region’s transit systems include vehicles, facilities, and fixed guideway that do not meet state of good repair thresholds defined by the federal government. Other transit assets, such as track signals and power systems, need maintenance and upgrades to support safe, reliable service. |

Identify and invest in priority transit state of good repair projects, as identified in Focus 40, TAM plans, and other prioritization processes. |

Proposed Program Transit Modernization Program

|

Transit Asset Modernization |

Obsolete infrastructure: Even if in a state of good repair, obsolete infrastructure inhibits transit systems’ abilities to adapt to change and serve customers. Examples of necessary upgrades include increasing the resiliency of transit system power supplies, incorporating modern doors and platforms into subway services, and making transit stations—such as Oak Grove Station and Natick Center Commuter Rail Station—fully accessible to people with disabilities. |

Support investments that improve the accessibility of transit stations, bus stops, and paratransit services, such as those identified through the MBTA’s Plan for Accessible Transit Infrastructure process. Support investments that upgrade transit fleets, facilities, and systems to provide more efficient, reliable, and sustainable service. Support climate vulnerability assessments and invest in projects and programs resulting from these processes. |

Existing Programs Bicycle Network and Pedestrian Connections Program Study issues through the Bicycle and Pedestrian Support Activities program (UPWP) Support MassDOT’s Climate Adaption Vulnerability Assessment and invest in recommended projects Proposed Program Transit Modernization Program Existing Study Research climate change resiliency options for transportation infrastructure |

Freight Network |

Many express highways are built to outdated design standards for trucks. Roads connecting to major freight facilities and routes need to support trucks as well as other types of vehicles. |

Maintain and modernize the roadway network. Improve connections between intermodal facilities and the regional road network. Maintain truck access on roadways designed to Complete Streets standards. |

Existing Programs Intersection Improvement Program Complete Streets Program Major Infrastructure Program Research strategies to improve bottleneck locations through the Bottleneck Program Proposed Program Interchange Modernization Program |

Climate Change Adaptation |

Some transportation facilities and infrastructure, including tunnels, are located in places vulnerable to flooding and other hazards. |

Retrofit or adapt infrastructure, including the Central Artery, to protect it from the impacts of hazards and climate change. |

Existing Programs Intersection Improvement Program Complete Streets Program Major Infrastructure Program Support to MassDOT’s Climate Adaption Vulnerability Assessment Proposed Program Interchange Modernization Program

Proposed Study Research climate change resiliency options for transportation infrastructure

Other Actions Coordinate with municipalities and state and regional agencies on ways that the MPO can support resiliency planning Emphasize TIP resiliency and adaptation criteria |

LRTP= Long-Range Transportation Plan. MassDOT= Massachusetts Department of Transportation. MBTA= Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. TAM = Transit Asset Management. UPWP = Unified Planning Work Program.

Source: Boston Region MPO.

The transportation system in the Boston region is, to a certain extent, increasingly stressed by the overall growth and success of the region’s economy. Congestion on the region’s roadways is reducing vehicular speeds, while the transit system is strained by high ridership and an aging infrastructure. Usage of the transportation network, both the roadway and transit systems, is projected to continue to increase more during the time period covered by the MPO’s LRTP, Destination 2040. In pursuit of the MPO’s core goals, the MPO and other stakeholders must find a way to manage the network’s capacity with limited capital funding to maximize mobility for all residents and users of the transportation network, including bicyclists and pedestrians.

One of the major challenges facing the MPO and other policymaking stakeholders and agencies is the preservation and enhancement of mobility options when economic growth and trip-making are concentrated in a limited geographic area. Economic growth in the Boston region outpaces that in the rest of the state, and growth in the Inner Core subregion is projected to continue at a faster rate than in the rest of the Boston region. The increase in the number of trips made in the Boston region is increasing congestion on a network that is either at capacity or nearing it. In an area where adding roadway capacity for vehicles is challenging, the MPO and other policymaking entities have the opportunity to work with municipalities to reallocate road space to accommodate all modes of travel. This finding has also been identified in the recently released MassDOT report, Congestion in the Commonwealth, Report to the Governor, 2019.