Chapter 4—Regionwide Needs Assessment

A critical early step in developing the LRTPis to gather, organize, and analyze available sources of data about the transportation system. This allows the MPO to understand the many needs that exist for all transportation modes.

After analyzing data included in the Web-based Needs Assessment described in Chapter 1, it is clear that the region has extensive maintenance and modernization requirements, including the need to address safety and mobility for all modes. MPO staff estimates that these needs likely would exceed the region’s anticipated financial resources between now and 2040. Therefore, the MPO must prioritize the region’s needs in order to guide investment decisions.

This chapter provides an overview of the MPO region’s transportation needs for the next twenty-five years. The information in this chapter has been organized according to the LRTP’s goals—which are used to evaluate projects in the Universe of Projects List both for scenario planning, and then project selection for the recommended LRTP. The LRTP’s goals are related to:

Information in each goal-based section of this chapter falls into these general categories:

Existing Goal:

Transportation by all modes will be safe.

Safety continues to be a top priority at the federal, state, and regional level. At the federal level, Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century’s (MAP-21) established a goal to achieve significant reduction in traffic fatalities and serious injuries on all public roads. At the state level, goals in the Massachusetts Strategic Highway Safety Plan (SHSP) include:

The MPO shares federal and state goals of reducing crash severity for all users of the transportation system. At the regional level, the MPO’s safety goal states, “transportation by all modes will be safe.” The MPO will support this goal by committing to take steps to reduce the number and severity of crashes, and serious injuries and fatalities caused by transportation modes. The MPO is making this commitment via two planning mechanisms currently in development: 1) the LRTP objectives, and 2) performance-measurement program.

The following is a list of safety needs identified through public outreach conducted in fall 2014, and on an ongoing basis through the MPO website:

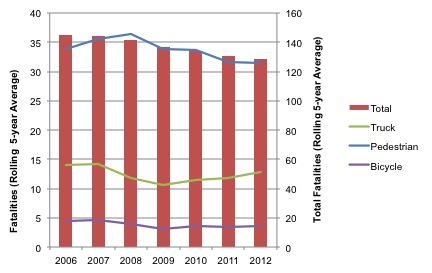

Overall, safety is improving in the region. Between 2006 and 2012, traffic fatalities (based on a rolling five-year average) decreased from 145 fatalities in 2006 to 129 in 2012. Figure 4.1 shows the change in traffic fatalities by mode during this time period and indicates that the 11 percent decline in fatalities included fewer automobile, truck, pedestrian, and bicycle fatalities. Similarly, total traffic crashes and injuries declined by 21 percent and 27 percent, respectively between 2006 and 2012.

FIGURE 4.1

Traffic Fatalities in the Boston Region MPO by Mode, 2006–2012

Source: Massachusetts Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration Fatality Reporting System, and the Massachusetts Department of Transportation Crash Data System.

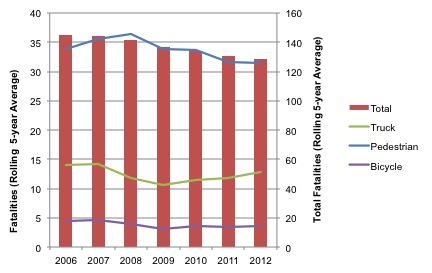

Despite these overall gains, crashes and injuries for pedestrians and bicyclists rose during this same period, as shown in Figure 4.2. Between 2006 and 2012, roughly two-thirds of pedestrian and bicycle crashes resulted in an injury. For pedestrians, the number of crashes increased by 18 percent and injuries grew by 31 percent. For bicycles, the number of crashes increased by 36 percent and injuries jumped by 46 percent.

FIGURE 4.2

Traffic Injuries in the Boston Region MPO by Mode, 2006–2012

Source: Massachusetts Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration Fatality Reporting System, and the Massachusetts Department of Transportation Crash Data System.

The most dangerous locations on the region’s roadway network are identified by using geographic information system (GIS) mapping to locate specific crash sites and the Equivalent Property Damage Only (EPDO) index to determine the severity of those crashes. The EPDO is a weighted index that assigns a value to each crash based on whether the accident resulted in a fatality, injuries, or property damage. A crash involving a fatality receives the most points (10), followed by a crash involving injuries (5), then a crash involving only property damage (1).

Crash data, which is compiled by the MassDOT Registry of Motor Vehicles, is analyzed for a three-year period to identify locations where multiple crashes have occurred. The combined EPDOs of the crashes in these so called “crash clusters” measure the severity of the safety problem at a particular intersection, highway interchange, or roadway segment.

Table 4.1 presents a list of the top-25 highway crash locations in the Boston region, based on EPDO from 2009 to 2011; and includes accompanying crash data from MassDOT’s Registry of Motor Vehicles.

TABLE 4.1

Top-25 Highway Crash Locations in the Boston Region MPO

| Municipalities |

EPDO |

Top 200 |

HSIP Crash Cluster |

Truck Crash Cluster |

Pedestrian Crash Cluster |

Bicycle Crash Cluster |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Interstate 93 at Columbia Rd |

Boston |

464 |

X |

X |

X |

blank |

X |

Middlesex Turnpike at Interstate 95 |

Burlington |

388 |

blank |

X |

X |

blank |

blank |

Rte 3 at Rte 18 (Main Street) |

Weymouth |

339 |

blank |

X |

X |

blank |

blank |

Interstate 93 (Near Ramps for Furnace Brook Parkway) |

Quincy |

330 |

blank |

X |

X |

blank |

blank |

East St Rotary at Rte 1 and Rte 128 |

Westwood |

328 |

blank |

X |

X |

blank |

blank |

Interstate 95 at Interstate 93 |

Reading |

326 |

X |

X |

X |

blank |

blank |

I-93 at Granite Ave (Exit 11) |

Milton |

325 |

blank |

X |

X |

blank |

blank |

Interstate 95 at Rte 2 |

Lexington |

324 |

blank |

X |

X |

blank |

blank |

Rte 9 at Interstate 95 |

Wellesley |

320 |

blank |

X |

X |

blank |

blank |

I-93 at North Washington St |

Boston |

319 |

blank |

X |

blank |

X |

blank |

I-93 at Rte 138 (Washington St) |

Canton |

316 |

blank |

X |

X |

blank |

blank |

I-93 at Rte 3A (Gallivan Blvd/Neponset Ave) |

Boston |

271 |

blank |

X |

X |

blank |

blank |

Interstate 95 at Rte 4 (Bedford St) |

Lexington |

270 |

blank |

X |

X |

blank |

blank |

Rte 18 (Main Street) at West St |

Weymouth |

247 |

X |

X |

X |

blank |

blank |

Interstate 93 at Rte 37 (Granite St) |

Braintree |

245 |

X |

X |

X |

blank |

blank |

Rte 139 (Lindelof Ave) at Rte 24 |

Stoughton |

240 |

blank |

X |

blank |

blank |

blank |

Interstate 93 at Leverett Connector |

Boston |

236 |

blank |

X |

blank |

blank |

blank |

Interstate 93 at Rte 28 |

Medford |

233 |

X |

X |

X |

blank |

blank |

Rte 128 at Rte 114 (Andover St) |

Peabody |

219 |

blank |

X |

X |

blank |

blank |

I-93 at Rte 28 and Mystic Ave |

Somerville |

214 |

X |

X |

X |

blank |

blank |

Storrow Dr at David G. Mugar Way |

Boston |

212 |

blank |

X |

blank |

blank |

blank |

Rte 28 (Randolph Ave) at Chickatawbut Rd |

Milton |

203 |

X |

X |

blank |

blank |

blank |

Rte 2 – Crosby’s Corner |

Concord/Lincoln |

200 |

X |

X |

blank |

blank |

blank |

Rte 1 at Rte 129 |

Lynnfield |

194 |

blank |

X |

X |

blank |

|

Rte 1 at Rte 129 (Walnut St) |

Saugus |

193 |

blank |

X |

blank |

blank |

blank |

EPDO = Equivalent Property Damage Only. HSIP = Highway Safety Improvement Program.

Source: MassDOT Registry of Motor Vehicles.

According to the MassachusettsSHSP, more than one in five fatalities in the state occurs at an intersection. Consistent with the SHSP, intersection safety remains an area of emphasis for the Boston Region MPO. Seventy-nine of the Top-200 Crash Locations are located in the Boston Region MPO. Corridors with multiple Top-200 Crash Locations include Route 9 in Natick and Framingham, Route 18 in Weymouth, Route 107 in Lynn, Route 16 in Newton and Wellesley, Route 126 in Bellingham, and Route 16 in Milford.

Strategies to address safety at intersections consist of geometric improvements to install exclusive left-turn lanes, align approaches, and modify turning radii.

Lane departures are one of the state’s nine areas of strategic emphasis, and a continuing priority of the Boston Region MPO. According to MassDOT data for the period 2004 to 2011, 55 percent of all roadway fatalities and 24 percent of all incapacitating injuries on roadways involved lane departure crashes. A lane departure crash is a non-intersection crash that occurs after a vehicle crosses the edge or center line, or otherwise leaves the traveled way. MPO staff compiled data on lane departure crashes in the Boston region, which indicate that a disproportionate share of lane departure crashes occur on interstates and arterials. Interstates make up five percent of lane miles in the region, yet account for nearly 15 percent of lane departure crashes. Similarly, arterials account for less than a quarter of the region’s lane miles, yet more than half of lane departure crashes. For interstates, there is a high prevalence of lane departure crashes along I-93 between I-90 and I-95 Northbound, I-93 between I-90 and I-95 Southbound, and I-495 between I-90 and I-95. For arterials, there is a high prevalence of lane departure crashes along Route 3 in Weymouth, Route 1 in Chelsea and Revere, the Jamaicaway in Boston, and Soldiers Field Road in Boston.

Strategies to address lane departure crashes consist of incorporating safety elements into roadway design and maintenance such as the addition of rumble strips, pavement markings, guardrails, or enhanced lighting and signage.

Pedestrians are one of the state’s nine strategic areas and an ongoing focus of the Boston Region MPO. As vulnerable users of the transportation system, pedestrians are more susceptible to risk than other roadway users. In the Boston region, pedestrians account for a growing share of crashes and a disproportionate share of injuries.

The MassDOT Crash Clusters map identifies the top pedestrian crash locations throughout the state. HSIP pedestrian clusters are locations with the highest crash severity for pedestrian-involved crashes based on EPDO. In the Boston region, there are many clusters in urban areas, including the downtown sections of Boston, Chelsea, Framingham, Lynn, Malden, Natick, Peabody, Salem, Waltham, and Wellesley; as well as along Massachusetts Avenue in Cambridge, Hancock Street in Quincy, and in Newton Centre, Watertown Square, and Davis Square in Somerville.

Strategies to address pedestrian safety at the HSIP pedestrian clusters consist of reducing traffic speeds, limiting pedestrian exposure to automobiles, and increasing motorists’ awareness and visibility of pedestrians. These infrastructure improvements take the form of traffic-calming measures, shortened crossing distances, turning restrictions, and enhanced signage and lighting.

There are also locations across the region where conditions remain unsafe for pedestrians, but which are not at the HSIP pedestrian cluster level. For less urban areas, sidewalk coverage is less extensive and often inconsistent. These inadequate facilities are an ongoing issue for suburban communities with a desire for more transit options. In addition, the need for adequate sidewalks should increase along with the region’s growing elderly population.

Bicyclists are one of the state’s four most proactive areas, and a growing priority of the Boston Region MPO. Similar to pedestrians, bicyclists also are vulnerable users of the transportation system and account for a growing share of crashes and a disproportionate share of injuries in the region.

The state also compiles high crash locations for bicycles. HSIP bicycle clusters are locations with the highest crash severity for bicycle-involved crashes based on EPDO. In the Boston region, there are multiple HSIP bicycle clusters in urban areas, ranging from the downtown sections of Beverly, Chelsea, Framingham, Lexington, Lynn, Natick, Salem, to Commonwealth Avenue in Boston, Harvard Street in Brookline, Massachusetts Avenue in Arlington and Cambridge, Main Street in Waltham, and Beacon Street and Somerville Avenue in Somerville.

During the past decade, the state has made substantial progress in expanding the bicycle network in order to increase bicycle usage and safety. Yet a majority of the region still lacks adequate bicycle infrastructure. The limits of the network also limit the likelihood of bicycling as a transportation option. Similar to other modes of travel, bicyclists require safe conditions, and an infrastructure to help create those desired conditions.

Strategies to address bicycle safety at the HSIP bicycle clusters consist of reducing traffic speeds, reducing conflicts between bicycles and motor vehicles, increasing separation between them, and increasing motorists’ awareness and visibility of bicyclists. These infrastructure improvements involve traffic-calming measures, separation between bicycles and motor vehicles (especially in high-speed traffic), turning restrictions, and enhanced signage and lighting, and increasingly are part of the MassDOT project design process.

Truck-involved crashes also are one of the state’s four proactive emphasis areas. As among the larger and heavier vehicles used in the transportation system, trucks account for a greater proportion of crash severity than other modes. Between 2006 and 2012, trucks made up approximately five percent of crashes, yet accounted for nine percent of fatalities.

MPO staff compiled high crash locations throughout the region based on truck-related EPDO. In the Boston region, the majority of high crash locations for trucks are located at older interchanges with obsolete designs. These interchanges connect express highways to express highways and express highways to arterials. Express highway to express highway interchanges with high truck crash severity includes I-95 interchanges at I-93 in Woburn, I-90 in Weston, and I-93 in Canton. Express highway to arterial interchanges with high truck crash severity includes I-95 interchanges at Route 1 in Dedham, Middlesex Turnpike in Burlington, and Route 138 in Canton.

Interchange modernization projects incorporate strategies to reduce the likelihood of rollovers at these obsolete interchanges by widening the turning radii or banking the roadway through tight curves.

Table 4.2 cites locations in the Boston Region MPO that have multiple safety needs, as described above.

TABLE 4.2

Locations with Multiple Safety Needs

| Municipalities |

T0p 200 |

HSIP Crash Cluster |

Truck Crash Cluster |

Pedestrian Crash Cluster |

Bicycle Crash Cluster |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Downtown Framingham |

Framingham |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

Rte 20 (Main Street) and Moody St |

Waltham |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

Watertown Square |

Watertown |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

Washington St |

Salem |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

Everett Ave |

Chelsea |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

Essex St |

Lynn |

X |

X |

blank |

X |

X |

Route 107 (Western Ave) |

Lynn |

X |

X |

X |

X |

blank |

Massachusetts Ave |

Arlington |

X |

X |

X |

X |

blank |

Rte 16 (Alewife Brook Parkway) |

Arlington, Somerville, Cambridge |

X |

X |

X |

blank |

X |

Broadway |

Chelsea |

blank |

X |

X |

X |

X |

Newtonville |

Newton |

blank |

X |

X |

X |

X |

Rte 16 (East Main St) |

Milford |

X |

X |

X |

blank |

blank |

I-495 at Rte 126 (Hartford Ave) |

Bellingham |

X |

X |

X |

blank |

blank |

Downtown Quincy |

Quincy |

X |

X |

blank |

X |

blank |

I-95 at Rte 16 (Washington St) |

Newton |

X |

X |

X |

blank |

blank |

Rte 16 (Revere Beach Parkway) |

Revere, Everett, Medford |

X |

X |

X |

blank |

blank |

I-495 at Rte 1A (South St) |

Wrentham |

X |

X |

X |

blank |

blank |

Rte 20 (East Main St) |

Marlborough |

X |

X |

X |

blank |

blank |

Rte 9 |

Framingham, Natick |

X |

X |

X |

blank |

blank |

Downtown Natick |

Natick |

blank |

X |

blank |

X |

X |

Downtown Lynn |

Lynn |

blank |

X |

blank |

X |

X |

Rte 1A |

Lynn |

blank |

X |

X |

X |

blank |

Rte 28 (McGrath Hwy) at Washington St |

Somerville |

blank |

X |

blank |

X |

X |

Newton Center |

Newton |

blank |

X |

blank |

X |

X |

Cambridge St |

Cambridge |

blank |

X |

blank |

X |

X |

Rte 16 (Mystic Valley Parkway) |

Medford |

blank |

X |

X |

X |

blank |

HSIP = Highway Safety Improvement Program.

Source: MassDOT Registry of Motor Vehicles.

Existing Goal:

Maintain the transportation system

System preservation is a priority for the MPO because the transportation infrastructure in the region is aging. The demands placed on highway and transit facilities have been taxing to the point that routine maintenance is insufficient to keep up with the need. As a result, there is a significant backlog of maintenance and state-of-good repair work to be done on the highway and transit system, including bridges, roadway pavement, transit rolling stock, and traffic and transit control equipment. Under these circumstances, system preservation and efficiency have become more important. Maintenance must receive attention, but because of the region’s financial constraints, the MPO will set priorities, considering the most crucial maintenance needs and the most effective ways to deploy funding.

In addition, the MPO agrees that if climate trends continue as projected, the conditions in the Boston region likely would include a rise in sea level coupled with storm-induced flooding, and warmer temperatures that would affect the region’s infrastructure, economy, human health, and natural resources. The MPO seeks to improve resiliency of infrastructure that could be affected by climate change through its evaluation criteria. The MPO rates projects on how well the proposed project design improves the infrastructure’s ability to respond to extreme conditions and addresses those impacts. This information helps guide decision making in the LRTP and TIP. The MPO also recognizes the need to keep major routes well maintained in order to respond to emergencies and evaluates projects on how well they improve emergency response or improve an evacuation route, diversion route, or an alternate diversion route.

The MPO, through its studies and freight-planning work also acknowledges that movement of freight is critical to the region’s economy. The majority of freight is moved by truck in this region. Major highway freight routes must be maintained to allow for the efficient movement of goods. The MPO also places special emphasis on protecting all freight network elements, including port facilities that are vulnerable to climate-change impacts.

Data in the application includes substandard bridges, emergency service routes, and locations of hospitals, emergency services, police, and fire stations. The application helps gauge a project’s ability to improve emergency response and response to extreme conditions.

The following is a list of needs identified through public outreach conducted in fall of 2014, and on an ongoing basis through the MPO website, as they relate to system preservation:

Unlike roadways, all bridges in the region are eligible to receive federal aid for maintenance and modernization projects. MassDOT and the MBTA prioritize resources for bridge preservation, as well as repair and replacement, and fund this work through the Statewide Bridge Program and MBTA bridge initiatives. MassDOT and the MBTA maintain a bridge management software tool (PONTIS) for recording, organizing, and analyzing bridge inventory and inspection data. PONTIS is used to guide the Statewide Bridge Program, which prioritizes resources for bridge preservation, as well as repair and replacement.

Of the 2,866 bridges located in the Boston Region MPO, 559 (19 percent) are considered functionally obsolete (do not meet current traffic demands or highway standards), and 154 (5 percent) are considered structurally deficient (deterioration has reduced the load-carrying capacity of the bridge).

Another important indicator of bridge condition is bridge health index. This is the ratio of the current condition of each bridge element to its perfect condition expressed as a score of 0 to 100; a value of zero indicates that all of a particular bridge’s elements are in the worst condition. A bridge health index of 85 indicates that the condition of a bridge is good. One-third of bridges (956) have health indices with a score 85 or greater; 36 percent (1029 bridges) have health indices of less than 85; and 31 percent (881 bridges) do not have core element data needed to calculate an index. An additional 44 bridges have health indices of zero. Approximately 43 percent of the latter are railroad bridges, 20 percent are pedestrian bridges, and an additional 20 percent of bridges are closed.

Currently, MassDOT is in the midst of making a $3 billion investment in its bridges. The Commonwealth instituted the eight-year Accelerated Bridge Program in 2008 to reduce the number of structurally deficient bridges. During the course of the program, the state plans to replace or repair more than 200 bridges. According to MassDOT, as of October 1, 2014, the ABP advertised 196 construction contracts with a combined budget valued at $2.43 billion. As of October 1, 2013, 52 projects in the Boston Region MPO area were substantially complete, 13 projects were under construction, and 15 projects were in design.

MassDOT, through its Office of Performance Management and Innovation, has developed a set of performance measures to address the state’s bridges: They are to:

The performance measure target of 463 structurally deficient bridges is approximately nine percent of bridges statewide. When comparing the statewide percentage to the structurally deficient bridges in the Boston Region MPO area, approximately five percent of bridges in the region are classified as structurally deficient. This indicates that MassDOT is addressing bridge maintenance needs in the region.

The performance measure of system-wide bridge health index for vehicular bridges in the Boston Region MPO area is 82.4. Again, this indicates that MassDOT is addressing bridge maintenance needs in the region.

The Boston Region MPO currently does not maintain an independent pavement management tool, but relies on MassDOT’s pavement management program. MassDOT’s program monitors approximately 4,150 lane miles of interstate, arterial, and access-controlled arterial roadways in the Boston Region MPO area. It has been the policy of the MPO not to fund resurfacing-only projects in the TIP. However, the MPO does make funding decisions for roadway reconstruction projects that include resurfacing, usually deep reconstruction, in addition to other design elements.

The Chapter 90 program (named for Chapter 90 of the Massachusetts General Laws), which is administered by MassDOT, also contributes to the Commonwealth’s strategy of preserving existing transportation facilities. This program supports construction and maintenance of roadways classified as local, i.e., work is performed by cities and towns of the Commonwealth. Typically, the majority of Chapter 90 allocations are used for road resurfacing and reconstruction. This program helps municipalities maintain and preserve locally owned roadways.

MassDOT, through its Office of Performance Management and Innovation, has developed a set of performance measures to address pavement management statewide. The measure ensures that at least 65% of National Highway System roadways are in good condition. The pavement serviceability index (PSI) measures the severity of cracking, rutting, raveling, and ride quality; and is reported on a scale from zero (impassible) to five (perfectly smooth).

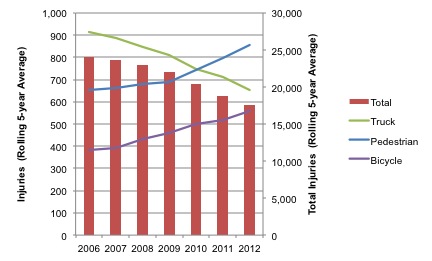

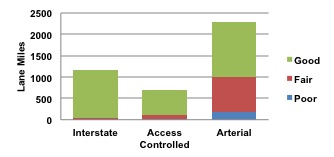

An analysis of the pavement on MassDOT-maintained roadways in the Boston Region MPO area indicates that approximately 70 percent are in good condition, 25 percent in fair condition, and 5 percent in poor condition—which meets MassDOT’s performance measure of at least 65 percent of the pavement in good condition. However, when this information is broken down further, looking at the pavement in poor condition by roadway type—interstate, arterial, and access-controlled arterials—MassDOT-maintained arterial roadways make up 62 percent of the monitored roadways, but 90 percent of the roadways that are in poor condition (see Figure 4.3).

FIGURE 4.3

Pavement Condition by Roadway Classification

Source: Massachusetts Department of Transportation Pavement Management Program.

Pavement data indicate that the majority of these arterial roadways are located in urban centers. The Pavement Condition map, in the LRTP Needs Assessment Application, shows larger expanses of arterial roadways with poor pavement condition in the Boston, Cambridge, Chelsea, Everett, Lynn, Malden, Medford, Newton, Revere, and Somerville urban centers. The MPO can address improved pavement condition in these areas through Complete Streets or bottleneck improvement projects if they are submitted for funding consideration.

Currently, the most pressing need that the MBTA faces is to bring the system into a state of good repair. Maintaining existing capital assets must be the highest priority for future investments or the quality of current services will degrade. Once the system is in a state of good repair, ongoing maintenance, replacement, and modernization of assets and infrastructure will be necessary to meet current and future demand for services. Providing sufficient resources for maintenance should be part of any program of system expansion.

The MBTA is developing a transit asset-management system to help address its capital needs. This program is using the MBTA’s state of good repair (SGR) database to help meet the new asset-management requirements under MAP-21, including:

In addition to monitoring the performance measures reported through the ScoreCard and using its existing service standards, the MBTA is in the process of determining whether additional performance measures should be incorporated into its service delivery policy. MPO staff will continue to coordinate with MassDOT and the MBTA as they develop their performance measures.

The MBTA has dedicated 100 percent of its federal formula funding, programmed through the LRTP and TIP, to maintenance and state-of-good repair projects. The MPO has not provided any of its target funding (those funds programmed at the MPO’s discretion) to the MBTA for maintenance needs in the past; however, it could in the future. This LRTP considers all transportation needs in the region, so the LRTP Needs Assessment identifies examples of transit needs in this category, including:

The MBTA is taking steps to address some of these issues:

In addition to these needs, the MBTA will provide the MPO with a list of unfunded state-of-good-repair transit projects once the MBTA’s Capital Investment Program document is completed. These unfunded needs can be considered for funding in an LRTP program.

The physical condition of the regional roadway network also influences the health of the freight transportation system. Maintaining and modernizing the roadway network directly benefits freight users. Many express highways were designed in the 1950s; highways constructed today are designed to higher standards that benefit both trucks and light vehicles. This is especially important for trucks, which are on average larger now than when these roads were built.

Intermodal freight connections in the Boston Region MPO area are almost all between rail and truck or between ship and truck. These intermodal terminals—whether publicly owned like the Conley Container Terminal in South Boston, or privately owned like the bulk commodity terminals on the Mystic and Chelsea Rivers—finance their terminal investments outside the MPO process. However, the MPO may identify opportunities to improve connections between these intermodal terminals and the regional road network. Alternatively, MPO analyses undertaken as part of the UPWP process may identify intermodal freight roadway improvements that could be implemented by others.

The system of arterial roadways that connect regional express highways with local freight transportation users is undergoing gradual transformation as sections are rebuilt to “complete streets” standards. The emerging practices of arterial roadway design may pose challenges for truck movements if accommodation for modern trucks is not addressed at the outset. Ironically, the viability of local merchants is a key “livability” goal, reversing overdependence on the mall retail concept. The ability of “Main Street” merchants to receive deliveries by truck needs to be understood as a requirement for their viability.

Given the shared use of the roadway system by freight and passenger vehicles, addressing the needs of the freight transportation system also will include broader automobile and bus transit mobility and safety needs. Freight priorities are stated with reference to specific freight concerns:

The MPO has developed an all-hazards planning application that shows the region’s transportation network in relation to natural hazard zones. This tool works in conjunction with the MPO’s database of LRTP and TIP projects so that it can be used to determine if proposed projects are located in areas prone to flooding or at risk of seawater inundation from hurricane storm surges, or, in the long term, sea level rise, which may be a result of climate change. Transportation facilities in such hazard zones might benefit from flood protection measures, such as enhanced drainage systems, or adaptations for sea level rise.

MassDOT is conducting a pilot project, Climate Change and Extreme Weather Vulnerability Assessment and Adaptation Options of the Central Artery. This study is assessing the vulnerability of the Central Artery to sea level rise and extreme storm events. It is investigating options to reduce identified vulnerabilities and establish an emergency response plan for tunnel protection and/or shut down in the event of a major storm.

Climate change impacts also present a number of planning challenges for the freight industry. In some ways, the freight transportation system is less vulnerable than other systems such as subways. Even on the shared roadway system freight is less vulnerable; because hazardous cargo is prohibited in tunnels, their transportation routes are designed using only above-ground roadways.

In addition, regional port facilities finance their own terminal investments outside of the MPO process. Recent and proposed port investments anticipate more severe storm surge conditions than found in the historical record, and associated MPO planning efforts can build on these new planning assumptions.

The MPO should continue to evaluate proposed projects to determine if they are located in areas prone to flooding, at risk of seawater inundation from hurricane storm surges, or, in the long term, sea-level rise because of climate change. The design of transportation projects in these hazard zones should address flood protection measures, such as enhanced drainage systems, or adaptations for sea-level rise, giving special attention to major infrastructure projects including tunnels and major freight routes and facilities.

Existing Goal:

Use existing facility capacity more efficiently and increase healthy transportation capacity

Through its capacity management and mobility goal and objectives, the MPO seeks to maximize the region’s existing transportation system so that both people and goods can move reliably and connect to key destinations. The Boston region is mature, which creates challenges to making major infrastructure changes to its transportation system. The Boston region also contains high population density and concentration of key destinations and is home to extensive and well-used roadway and public transit networks. These networks provide a solid foundation that—through targeted improvements to bottlenecks and utilizing management and operations strategies—can accommodate the ways the region is expected to change and grow.

The MPO’s capacity management and mobility goal and objectives also seek to expand travelers’ travel options to reach principal destinations. One approach to increasing mobility is to reduce single-occupancy vehicle travel, which may be achieved by encouraging multi-modal transportation options, including public transportation and bicycle and pedestrian transportation, in addition to automobile travel. The MPO’s goals and objectives respond to federal, state, and regional activities to increase transit, bicycle, and pedestrian travel, such as MassDOT’s GreenDOT initiative, the MassDOT Mode Shift Goal, the Healthy Transportation Compact, and MetroFuture’s transportation goals, objectives, and strategies. They also respond to increasing demand for transit, bicycle, and pedestrian connections by communities throughout the region.

The MPO monitors the mobility of its roadways as part of its Congestion Management Process (CMP), which also includes activities to monitor high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) lanes, public transportation, and park-and-ride lot usage. It is essential to keep all transportation facilities functioning at their optimum levels because how these facilities perform affect roadway and transit congestion. Improving congestion will ease the economic loss caused by travel delay, help increase mobility, and decrease vehicle emissions.

In order to determine how well the region’s roadways are performing, the MPO applies performance measures that gauge the duration, extent, intensity, and reliability of congestion. MPO staff analyzed congestion in the region using the CMP Express Highway and Arterial Performance Dashboards, which applied the following measures:

Tables 4.3 and 4.4 show the performance measure values of the duration, intensity, and reliability of congestion for the region’s expressways and arterials. Figures 4.4 and 4.5 show the performance values of the extent of congestion for the region’s expressway and arterials.

TABLE 4.3

Regional Performance for Expressways

Performance Measure |

Value |

|---|---|

AM Average Speed |

57.81 mph |

AM Speed Index |

0.99 |

AM Travel Time Index |

1.12 |

PM Average Speed |

58.53 mph |

PM Speed Index |

1.01 |

PM Travel Time Index |

1.11 |

Free Flow Speed |

65.28 mph |

Average Congested Time per AM Peak Period Hour |

6.82 Minutes |

Average Congested Time per PM Peak Period Hour |

5.92 Minutes |

Source: Boston Region MPO Congestion Management Process.

TABLE 4.4

Regional Performance for Arterials

Performance Measure |

Value |

|---|---|

AM Average Speed |

31.57 mph |

AM Speed Index |

0.86 |

AM Travel Time Index |

1.09 |

PM Average Speed |

31.92 mph |

PM Speed Index |

0.87 |

PM Travel Time Index |

1.07 |

Free Flow Speed |

34.27 mph |

Average Congested Time per AM Peak-Period Hour |

2.95 Minutes |

Average Congested Time per PM Peak-Period Hour |

2.34 Minutes |

Source: Boston Region MPO Congestion Management Process.

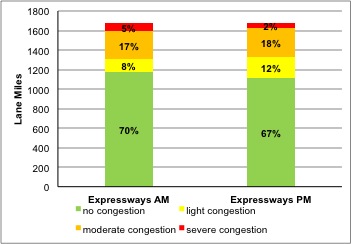

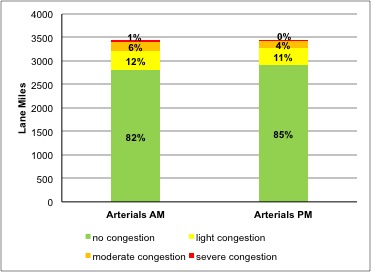

Lane miles of congestion, as measured by travel time index, measure the extent of congestion on the roadway network. This was analyzed for the entire CMP expressway network. Overall, 30 percent of all expressway lane miles in the AM peak period and 32 percent of all expressway lane miles in PM peak period experience congestion to some degree. Lane miles of congestion for the arterials are significantly less, at 18 percent for the AM peak period and 15 percent for the PM peak period.

FIGURE 4.4

Lane Miles of Congestion: CMP Monitored Expressways

FIGURE 4.5

Lane Miles of Congestion: CMP Monitored Arterials

Based on this data, the MPO has identified several general trends for the region’s expressways and arterials:

The MPO also must address the transportation system’s ability to move freight efficiently, as this contributes significantly to the region’s economic vitality. The freight transportation system consists of a very large number of enterprises operating many distinct types of equipment over both publicly and privately owned or managed transportation networks. Key components of this system include the public roadway network, the rail system (both the publicly and privately owned sections), and navigable waterways. A number of specialized terminals (both publicly and privately owned) connect and allow freight to transfer between these different systems.

The roadway network is the most important component of the freight transportation system in the Boston Region MPO area. Trucks are the dominant mode for freight movement in this area; and virtually all freight that moves by rail or water requires transshipment to or from trucks in order to serve regional freight customers.

Trucks share the regional roadway network with light vehicles, both commercial and private. Measuring, managing, and reducing delay in the region’s road network is an important defined responsibility of the MPO and is the ongoing work of the MPO’s Congestion Management Process. Freight movements are expected to increase gradually into the near future in conjunction with population and economic growth. Strategies to affect mode shift in the MPO region are not applicable to freight, since no practical alternatives to trucks exist for final distribution of consumer goods to retail locations, as well as for most industrial logistic needs.

Railroads have been successful in increasing intermodal shipments using high-capacity double-stacked rail services to modern terminals, such as the one in Worcester. These expanded rail services slow the growth of trucks on the national interstate system, but add increasing numbers of trucks to roadways within the MPO. The impacts of larger vessels using an expanded Conley Terminal are similar.

Given the shared use of the road network, it is important that policies and investments that control or reduce congestion improve parts of the network heavily used by trucks. Fortunately, there is a strong correlation between parts of the road network experiencing severe congestion and parts heavily used by trucks.

The MPO region is served by variety of transit services:

To date, most of the Boston Region MPO’s target funding for capital projects has gone to support the roadway network, bicycle, and pedestrian facilities; with the region’s RTAs, the MassDOT Rail and Transit Division, and others supporting investment in the transit system. The MPO has made some investments in the transit system in recent years through its Suburban Mobility Program, which evolved into the Clean Air and Mobility Program, These programs have allocated Congestion Mitigation Air Quality (CMAQ) funding for starting up new, locally developed and supported transit services that improve air quality and reduce congestion. The MPO also supports the distribution of federal transit grant funds by the Rail and Transit Division.

Like the region’s roadway system, the region’s transit services and networks face reliability and capacity-management concerns. Buses, trackless trolleys, and shuttles operating on roadways are affected by traffic congestion. The size of vehicle fleets, the capacity of individual vehicles, and the condition of vehicles and infrastructure all have an impact on the number of passengers that can be moved and the ability of services to adhere to schedules.

The region’s transit services also should provide connectivity to housing, employment, and other key destinations, as well as to other passenger transportation modes. Table 4.5 describes the portion of the MPO’s population and employment in 2010 that fell within one-quarter mile of an MBTA, CATA, or MWRTA bus stop or an MBTA rapid transit or commuter rail station, as well as the amount projected to fall within the walkshed in 2040. Modest population gains are expected within this existing walkshed over the next 25 years.

Table 4.5

Population and Employment within One-quarter Mile of an MBTA, CATA or MWRTA Bus Stop, Rapid Transit Station, or Commuter Rail Station, by MAPC Community Type (2010 and 2040)

MPO Region Population |

MPO Region Employment(2010) |

MPO Region Population (2040) |

MPO Region Employment (2040) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

Within MBTA, CATA, MWRTA Walkshed |

1,756,000 |

1,292,600 |

2,115,200 |

1,418,900 |

MPO Total |

3,162,300 |

2,028,500 |

3,732,900 |

2,209,400 |

Percent |

55.5% |

63.7% |

56.7% |

64.2% |

Note: Population and employment results rounded to the nearest hundred.

Source: Central Transportation Planning Staff.

Table 4.6 and 4.7 describes the portion of the MPO’s 2010 and 2040 population by community type2 that is projected to fall within the MBTA, CATA, or MWRTA fixed-route station walkshed. Table 4.8 and 4.9 describes the portion of the MPO’s employment by area type that is projected to fall within the walkshed in 2010 and 2040.

Table 4.6

Population within One-Quarter Mile of Transit (MBTA, CATA or MWRTA Bus Stop, Rapid Transit Station, or Commuter Rail Station), by MAPC Community Type (2010)

|

Regional Urban Centers |

|

|

Total MPO Region |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Within Transit Walkshed |

1,196,200 |

328,900 |

207,900 |

23,000 |

1,756,000 |

MPO Total |

1,391,300 |

545,300 |

900,500 |

325,100 |

3,162,300 |

Percent |

86.0% |

60.3% |

23.1% |

7.1% |

55.5% |

Note: Population and employment results rounded to the nearest hundred.

Source: Central Transportation Planning Staff.

Table 4.7

Population within One-Quarter Mile of Transit (MBTA, CATA or MWRTA Bus Stop, Rapid Transit Station, or Commuter Rail Station), by MAPC Community Type (2040)

|

Regional Urban Centers |

|

|

Total MPO Region |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Within Transit Walkshed |

1,454,800 |

392,200 |

242,000 |

26,200 |

2,115,200 |

MPO Total |

1,688,700 |

651,100 |

1,029,900 |

363,300 |

3,732,900 |

Percent |

86.1% |

60.2% |

23.5% |

7.2% |

56.7% |

Note: Population and employment results rounded to the nearest hundred.

Source: Central Transportation Planning Staff.

Table 4.8

Employment within One-Quarter Mile of Transit (MBTA, CATA or MWRTA Bus Stop, Rapid Transit Station, or Commuter Rail Station), by MAPC Community Type (2010)

|

Regional Urban Centers |

|

|

Total MPO Region |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Within Transit Walkshed |

922,400 |

194,200 |

164,200 |

11,800 |

1,292,600 |

MPO Total |

1,048,600 |

313,600 |

514,700 |

151,700 |

2,028,500 |

Percent |

88.0% |

61.9% |

31.9% |

7.8% |

63.7% |

Note: Population and employment results rounded to the nearest hundred.

Source: Central Transportation Planning Staff.

Table 4.9

Employment within One-Quarter Mile of Transit (MBTA, CATA or MWRTA Bus Stop, Rapid Transit Station, or Commuter Rail Station), by MAPC Community Type (2040)

|

Regional Urban Centers |

|

|

Total MPO Region |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Within Transit Walkshed |

1,017,600 |

210,400 |

178,500 |

12,400 |

1,418,900 |

MPO Total |

1,151,900 |

340,200 |

556,200 |

161,100 |

2,209,400 |

Percent |

88.3% |

61.8% |

32.1% |

7.7% |

64.2% |

Note: Population and employment results rounded to the nearest hundred.

Source: Central Transportation Planning Staff.

Tables 4.7 and 4.9 show that in 2040 relatively low portions of population and employment in maturing and developing suburbs are projected to fall within the MBTA, CATA, and MWRTA fixed-route walkshed. This suggests that transit services may need to be expanded or diversified in order to increase transit use within these parts of the MPO region.

As part of providing connections to key destinations, transit services and stations should support “last-mile” connections by linking to bicycle and pedestrian routes and shuttle or other services; parking for vehicles and bicycles also should be made available, where appropriate. Transit services should account for the travel needs associated with non-work trips, as well as reverse commutes and other types of trip-making activity. Finally, these services and facilities should account for the needs of a diverse population of riders, which include young people, older adults, and persons with disabilities.

The MPO agrees that bicycle and pedestrian facilities provide opportunities for healthy, environmentally sustainable travel. Federal, state, regional and local initiatives supporting Complete Streets underscore interest in integrating and enhancing the role of these modes in the transportation system. For example, MassDOT issued its Complete Streets design standards and related Healthy Transportation Policy Directive to ensure that MassDOT projects are designed and implemented so that all customers have access to safe and comfortable walking, bicycling, and transit options.

MassDOT also supports the Bay State Greenway (BSG), a seven-corridor network of bicycle routes that comprise both on- and off-road bicycle facilities throughout the state intended to support long-distance bicycle transportation. Approximately 200 miles of this 750-plus mile on- and off-road network have been constructed. MassDOT has identified the “BSG Priority 100,” one-hundred miles of high-priority shared-use path projects within the network.

On-road bike routes, separated paths, sidewalks, and other supporting infrastructure are a key component of the last-mile connections described. When these facilities are integrated into well-connected networks, they support trips both within and between the region’s communities. When they are connected to key destinations, they can support a diversity of trip types, and effective connections between facilities can support longer trips.

Today, approximately three percent of the region’s non-limited-access roadways provide bicycle accommodations—a more-than 50 percent increase since the previous Boston Region MPO LRTP. Tables 4.10 and 4.11 below show the portion of the MPO’s population and employment that fell within one-half mile of a bike facility in 2010.

Table 4.10

MPO-Region Population within One-half Mile of a Bike Facility (2010)

MPO Population |

Inner Core Communities |

Regional Urban Centers |

Maturing Suburbs |

Developing Suburbs |

Total MPO Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Within One-Half Mile of Bike Facility |

1,120,900 |

105,100 |

189,500 |

22,700 |

1,438,100 |

Total |

1,391,300 |

545,300 |

900,500 |

325,100 |

3,162,300 |

Percent |

80.6% |

19.3% |

21.0% |

7.0% |

45.5% |

Note: Population and employment results rounded to the nearest hundred. Interstates and access controlled roads excluded from analysis.

Source: Central Transportation Planning Staff.

Table 4.11

MPO-Region Employment within One-half Mile of a Bike Facility (2010)

MPO Employment |

Inner Core Communities |

Regional Urban Centers |

Maturing Suburbs |

Developing Suburbs |

Total MPO Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Within One-Half Mile of Bike Facility |

843,300 |

51,200 |

129,800 |

10,800 |

1,035,100 |

MPO Total |

1,048,600 |

313,600 |

514,600 |

151,700 |

2,028,500 |

Percent |

80.4% |

16.3% |

25.2% |

7.1% |

51.0% |

Note: Population and employment results rounded to the nearest hundred. Interstates and access controlled roads excluded from analysis.

Source: Central Transportation Planning Staff.

As the tables above show, the proportion of MPO employment that fell within one-half mile of a bicycle facility in 2010 was larger than the portion of MPO population that was within one-half mile of a bicycle facility. As of 2010, approximately 80 percent of population and employment in Inner Core Communities was located within one-half mile of a bicycle facility. In comparison, much lower shares of population and employment are within one-half mile of bicycle facilities in communities characterized as regional urban centers, maturing suburbs, and developing suburbs.

The MPO has analyzed patterns of regional bicycling activity using data from the 2011 Massachusetts Travel Survey. Table 4.12 shows the miles traveled per 1,000 residents for communities in the Boston Region, by Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC) community type.

Table 4.12

Miles by Bicycle per 1,000 Residents for Communities in the Boston MPO Region, by MAPC Community Type (2011)

Total Distance |

Between Home and Work |

Other Travel |

|

|---|---|---|---|

Inner Core Communities |

184 |

100 |

84 |

Maturing Suburbs |

57 |

19 |

38 |

Regional Centers |

21 |

6 |

15 |

Developing Suburbs |

32 |

7 |

25 |

Source: Massachusetts Travel Survey, 2011.

Bicycling, including for trips to work is highest in Boston’s Inner Core communities, followed by its maturing suburbs. These bicycling activity levels are correlated with the portions of population and employment within one-half mile of a bicycling facility in each of the MAPC community types, as shown in tables 5 and 6 above. The MPO’s capacity management and mobility objectives include an objective to increase the percentage of population and places of employment with access to bicycle facilities. The greatest potential for these increases exists in the maturing suburbs, regional urban centers, and developing suburbs in the Boston region, and by increasing bicycle network connectivity to key destinations in these areas, there may be growth in bicycling activity.

The following is a list of needs identified through public outreach conducted in fall 2014, and on an ongoing basis through the MPO website, as they relate to capacity management and mobility:

MPO activities and investments to increase reliability on the roadway network benefit both freight and non-freight road users. The MPO has identified a priority set of congested locations on the region’s expressways and arterials using four measures: speed index, travel time index, volume-to-capacity ratio, and crash history. Each corridor was given a weighted score depending on the number of performance measures that indicated congestion. Below is a list of expressway and arterial corridors along with their corresponding LRTP needs assessment corridor.

As discussed above, work on these priority expressways and arterials should consider the transportation needs of passengers and freight, as well as ways to accommodate transit, bicycling and walking.

The MBTA Scorecard reports on various performance measures for the bus system as a whole, for individual rapid transit lines, for the commuter rail system as a whole, and for individual commuter rail lines. An analysis of monthly scorecards for 2013 reveals that:

As mentioned above, the majority of transit capacity and expansion needs are funded by federal agencies, MassDOT, the region’s RTAs, and other entities. A number of major infrastructure constraints on the MBTA system limit capacity and hinder the agency’s ability to expand the system in the future. Most of these constraints are mentioned in Paths to A Sustainable Region, the previous LRTP, which include, but are not limited to, the following:

A recent analysis of the MBTA’s current Program for Mass Transportation (PMT) identified several locations and facilities with transit needs. These include, but are not limited to the following:

In addition, the MBTA will provide the MPO with a list of capacity and mobility improvement projects once the MBTA’s Capital Investment Program document is released for public review.

MPO staff has also identified several transit capacity and service needs through public outreach:

Transit connectivity includes connections to other modes at stations or stops, as well as broader connectivity to employment, housing, and other key destinations. Multi-modal connections at stations and stops take into account parking availability and bicycle and pedestrian links. MPO staff analyzed patterns of parking utilization on the MBTA system to determine which park-and-ride lots and bicycle facilities were congested. Any parking lot or bicycle facility that is more than 85 percent utilized is considered congested; these facilities are listed below:

MPO staff has also identified needs related to bicycle and pedestrian connections at stations:

MPO staff has identified several transit connectivity needs—both to transit facilities and destinations throughout the region—through reviews of the Program for Mass Transportation, and other public outreach and analysis:

In 2014, MPO staff completed its Bicycle Network Evaluation, which assessed gaps in the MPO’s existing bicycle network according to how well connections in these areas would support bicycle connectivity and maximize safe access throughout the region. A steering committee of bicycle representatives from MassDOT and MAPC guided this project, and advocacy groups and bicycling stakeholders in the region provided input. Staff evaluated more than 230 gaps and ranked these gaps using evaluation criteria pertaining to bicycle connectivity.

Through this evaluation process, MPO staff identified eleven top priorities.\

Progress on these eleven identified priorities varies by gap. For example, some still need further planning and design, others have right-of-way or land-ownership challenges, yet others are proposed for funding. In addition, as part of the Bicycle Network Evaluation, MPO staff noted that there are areas within the region, such as the Three Rivers Interlocal Council and South Shore Coalition subregions, with so few bicycle facilities (on-road lanes, protected lanes, or off-road paths) that they did not meet the definitions for gaps in the study. Staff recommended that existing desire lines for facilities in these areas be considered in subsequent evaluations.

In addition to the priority connections identified through the Bicycle Network Evaluation, several BSG 100 priority corridor projects are within the MPO region:

Progress has been made on a number of these projects; several have been proposed for TIP funding, and some are being advanced by other entities.

Through outreach and analysis, MPO staff has identified additional needs related to bicycle and pedestrian connectivity, and which address a combination of specific locations and broader themes:

Existing Goal:

Create an environmentally friendly transportation system

The Boston Region MPO agrees that greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) contribute to climate change. If climate trends continue as projected, the conditions in the Boston region will include a rise in sea level coupled with storm-induced flooding, and warmer temperatures that would affect the region’s infrastructure, economy, human health, and natural resources. Massachusetts is responding to this challenge by taking action to reduce the GHGs produced by the state, including those generated by the transportation sector. To that end, Massachusetts passed its Global Warming Solutions Act, which requires reductions of GHGs by 2020, and further reductions by 2050, relative to 1990 baseline conditions. Understanding that reducing the use of single-occupant vehicles also would scale back production of GHGs and other pollutants, Massachusetts has a goal of tripling the share of travel in Massachusetts by bicycling, using transit and walking by 2030.

In addition, the MPO analyzes and monitors the presence of other air quality pollutants—volatile organic compounds (VOC), nitrogen oxides (NOx), carbon monoxide (CO), and particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10) from transportation in the region. The MPO region was classified as attainment for ozone (formed from VOC and NOx emissions) in 2012. The Boston Region MPO is in attainment with the PM standards, but remains in maintenance for CO.

Contributing to this improved air quality status is the MPO’s attention to accomplishing the State Implementation Plan Commitments from the Central Artery/Third Harbor Tunnel project, and other measures and projects funded in the LRTP and TIP to reduce congestion and improve transit and active modes of transportation. Although the MPO area is in attainment and maintenance for these specific air quality standards, its goal is to continue to reduce emissions of these pollutants.

In addition to air quality, the MPO consults with agencies responsible for land management, natural resources, historic preservation, and environmental protection and conservation as related to transportation initiatives. Natural, environmental, and historic resources were mapped for the Boston region using information from the Commonwealth’s Office of Geographic and Environmental Information Systems MassGIS). The MPO considers environmental impacts that stem from transportation projects, including areas of critical environmental concern, special flood hazard areas, wetlands, water supply, protected open space, endangered species, and brownfield and superfund sites. In the Boston region, environmental reviews for projects are conducted by the proponent transportation agency or municipality. The environmental reviews occur when each of the projects is in the design phase and prior to being funded for construction. Impacts to these resources from the project are factored into project evaluations through the MPO’s evaluation criteria.

Environment

Air Pollution

Environment

The MPO addresses environmental impacts through its evaluation criteria, rating projects on how they address impacts in these areas prior to programming projects in the LRTP and TIP. The following information is available by accessing the LRTP Needs Assessment tool, which will direct you to the Massachusetts geographic information system (GIS) website. In addition, the MPO’s All-Hazards Application described above provides information about some of the items listed below.

The following is a list of needs identified through public outreach conducted in the fall of 2014, and on an ongoing basis through the MPO website, as they relate to clean air and clean communities:

The MPO’s policy is to address climate change, reduce air pollution, and avoid harmful effects to the environment. The MPO should continue monitoring the estimated or projected levels of pollutants (VOC, NOx, CO, PM, and CO2). It should use this information to guide planning and programming in its LRTP, TIP, studies or individual projects outlined in the UPWP, and project work for various transportation agencies. In both the LRTP and TIP project-selection processes, the MPO reviews and rates projects on how well they meet criteria established to protect the environment.

Many of the objectives established under the goals of Capacity Management and Mobility will help the MPO to meet the Clean Air and Clean Communities goal in the future. It encourages programs that would help reduce vehicle-miles of travel (VMT), which in turn would help reduce emissions of VOC, NOx, CO, CO2, and PM.

Environmental impacts of projects will continue to be reviewed at the individual project level as they are submitted for funding consideration in the LRTP and TIP. A qualitative evaluation is done for projects in the conceptual design phase using the MPO’s All-Hazards Planning Application. A more detailed evaluation is possible for projects that are further along in design.

Existing Goal:

Provide comparable transportation access and service quality among communities, regardless of income level or minority population

The MPO’s Transportation Equity goal is to provide comparable transportation access and service quality among communities regardless of income level or minority status. To accomplish this, the MPO will target investments to areas that benefit a high percentage of low-income and minority populations, minimize any burdens associated with MPO-funded projects in low-income and minority areas, and break down barriers to participation in MPO decision making.

The following is a list of needs identified through public outreach conducted throughout 2014, and on an ongoing basis through the MPO website, as they relate to transportation equity:

The MPO determines the transportation needs of people in environmental-justice areas in a number of ways. Staff posts a needs survey on the MPO’s website; the MPO conducts forums and meetings to solicit input; staff attend various meetings where needs and transportation gaps are discussed; and staff keep current on reports and studies that identify these needs. Identified needs generally fall into several categories, including:

The MPO addresses regional transportation equity needs through TIP evaluation criteria, where projects that address a transportation issue in an environmental-justice neighborhood can score points. MPO staff gives positive ratings to projects that could benefit environmental-justice areas, and negative ratings to projects that might burden these areas. This scoring system gives projects that address transportation equity issues an advantage, as the MPO considers these ratings when deciding what projects should be funded in the LRTP or TIP.

Existing Goal:

Ensure our transportation network provides a strong foundation for economic vitality

Land use decisions and many economic development decisions in Massachusetts are controlled directly by local municipalities through zoning—as guided by a significant body of laws and regulations enacted by the state legislature. At the regional level, MAPC is the regional planning agency that represents the 101 cities and towns in the metropolitan Boston area and the Boston Region MPO. The MPO relies on MAPC to develop the region’s population and employment projections for use in transportation planning. MAPC also coordinates and consults with the region’s municipalities regarding these projections, and reviews and evaluates land use and economic-development plans and their relationship to MPO planning.

MAPC created MetroFuture, a plan to make a “greater” Boston region—to better the lives of the people who live and work in metropolitan Boston, now and in the future. The MPO adopted this plan as its land use plan for the Boston Region MPO area. One of MetroFuture’s implementation strategies is to focus on economic growth, and coordinate transportation investments to guide economic growth in the region.

The following is a list of needs identified through public outreach conducted in the fall of 2014, and on an ongoing basis through the MPO website, as they relate to economic vitality:

MassDOT, the Massachusetts Executive Office of Housing and Economic Development (EOHED), and the Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs (EOEEA) joined together to highlight their common strategy and commitment to the Commonwealth’s sustainable development and the “Planning Ahead for Growth” strategy. This strategy calls for identification of priority areas where growth and preservation should occur.

MAPC worked with EOHED and the EOEEA to develop a process to identify local, regional, and state-level priority development and preservation areas in municipalities within the MPO area. MAPC staff worked with municipalities and state partners to identify locations throughout the region that are principal supporters of additional housing, employment growth, creation and preservation of open space, and the infrastructure improvements required to support these outcomes for each location. This process identified locations that are best suited to support the type of continued economic vitality and future growth that the market demands, and which communities desire. Identifying these key growth and preservation locations also helps MAPC, the Boston Region MPO, and state agencies to understand both the infrastructure and technical assistance needs better, in order to help them prioritize the limited regional and state funding.

Economic development effects will be considered at the individual project level as projects are submitted for funding in the LRTP and TIP. Projects will be evaluated based on their proximity to the priority development areas and how well the transportation project or program would address existing and proposed economic development needs in the area.

1 The morning peak period is from 6:00 AM to 10:00 AM, and the evening peak period is from 3:00 PM to 7:00 PM.

2 The Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC) has developed a classification system that organizes Massachusetts’ cities and towns into one of five types, four of which are present in the Boston region. These types can be used to understand how demographic, economic, transportation and other trends may affect different communities in the region. For more information, visit http://www.mapc.org/publications.