Roadway-Pricing Strategies

TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM

DATE: December 21, 2023

TO: Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO)

FROM: Seth Asante and Ryan Hicks, MPO Staff

RE: Learning from Roadway-Pricing Experiences

According to INRIX (a transportation analytics firm), Boston was ranked the second most congested city in the United States and the fourth most congested city in the world in 2022.1 Based on INRIX data, an average driver spent 134 hours stuck in congestion over the year and the estimated cost of congestion per driver was reported to be $2,270, making it even more pressing to explore congestion mitigation options, such as roadway pricing. Roadway-pricing strategies have been implemented throughout the United States with three primary goals: reducing congestion and greenhouse gas emissions, generating funds to maintain highway and public transportation infrastructure, and managing travel demand by encouraging single-occupancy private automobile drivers to shift their trips to active transportation modes or travel routes, or to high-occupancy vehicles, or to travel during off-peak periods.

Through the Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization’s (MPO) Unified Planning Work Program discrete projects program, the Boston Region MPO elected to fund the “Learning from Roadway-Pricing Experiences” study with its federally allocated metropolitan planning funds during federal fiscal year (FFY) 2023.2 The purpose of this study is to identify the political, institutional, and technological challenges and opportunities that arise from implementing roadway-pricing strategies, so that MPO staff can learn from them and provide the MPO Board with keys to successful implementation, potential MPO goals for roadway pricing, and ideas for exploring roadway pricing in the MPO planning process. The study also identifies the essential principles that should be followed for implementing successful roadway-pricing programs based on existing roadway-pricing programs around the country.

To accomplish the goal and objectives of the study, MPO staff completed a series of tasks for this study. First, staff identified and selected existing roadway-pricing programs that would be suitable for stakeholder interviews. Interviews were then conducted with key personnel, which either created or helped manage the selected roadway-pricing programs. In addition, staff, with the help of the Congestion Management Process (CMP) Committee, identified MPO goals for roadway pricing and explored roadway pricing in relation to the MPO planning process. Lastly, this memorandum was written to document and summarize the results of this study as well as the various roadway-pricing strategies and lessons learned.

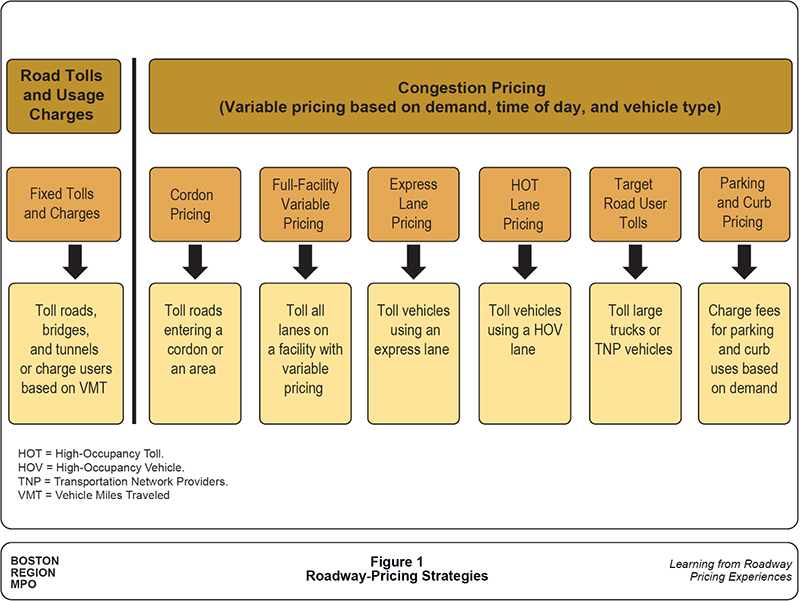

Roadway-pricing strategies fall into two broad categories: road toll and usage charges and congestion pricing. Figure 1 shows strategies related to both categories. Road tolls are a common way to maximize revenue to pay for highway and bridge improvement costs. Road tolls rarely vary by time of day and are not intended to reduce congestion. A road usage charge (RUC) allows all users of a transportation system to help pay for that system in a fair manner and in proportion to how much it is used, and it is often referred to as a mileage-based user fee, vehicle miles traveled tax, or distance-based fee. Congestion pricing typically varies by time of day and focuses on adjusting user fees during peak periods to mitigate congestion. In most cases, the primary goal of a congestion pricing program is to relieve congestion, not raise revenue. Other goals of congestion pricing include shifting demand to other modes of transportation, spreading trips to off-peak times, and reducing air pollution. An existing toll facility may be updated so that it meets the criteria of congestion pricing by increasing prices under congested conditions.

The following are the different forms of roadway-pricing strategies:

Roadway-pricing strategies typically provide subsidies to address equity issues and reduce pollution. Free or discounted usage of congestion-pricing facilities is permitted for certain vehicle types, depending on their role in society and their impact on the environment, such as clean-fuel and electric vehicles, emergency and transit vehicles, and carpools. In addition, subsidies are considered for low-income populations and other groups who may be adversely burdened by the costs on certain congestion-pricing facilities.

Figure 1

Roadway-Pricing Strategies

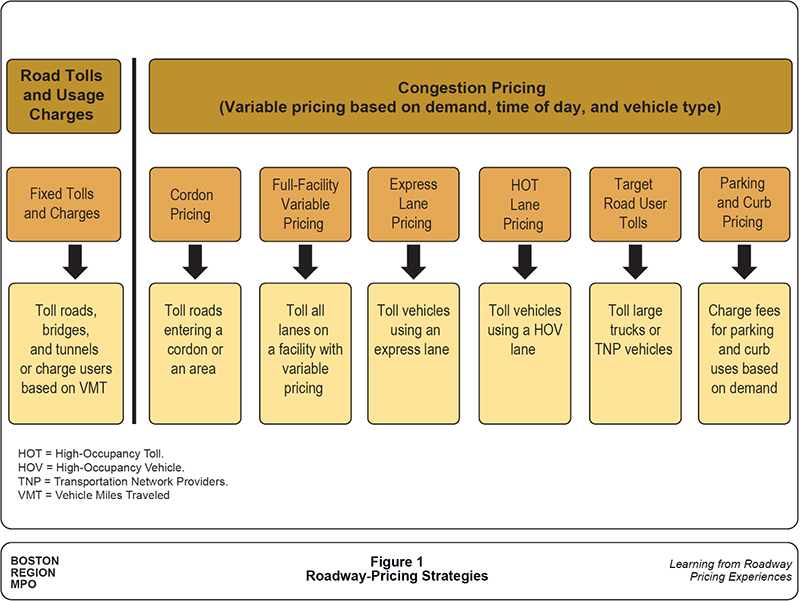

MPO staff identified 13 roadway-pricing programs in the United States that were reviewed as part of this study, which were presented to the CMP Committee on March 23, 2023, for discussion. Figure 2 maps the locations of the 13 programs. Table 1 in Appendix A presents information on each program including the program description, purpose or goals, roadway-pricing policy, challenges, and considerations for incorporating congestion pricing in the planning process. The CMP Committee provided feedback on which roadway-pricing programs to explore further through interviews with key personnel associated with the programs.

The CMP Committee expressed interest in roadway-pricing programs that

The CMP Committee also expressed interest in a selection of programs to study that

Table 2 in Appendix A shows the 13 programs, the selection criteria, and the five highlighted programs that were selected for interviews.

Figure 2

Locations of the 13 Roadway-Pricing Programs

As a result of the discussion at the CMP Committee meeting, the following programs were selected for further exploration:

In June and July of 2023, Boston Region MPO staff interviewed managers and designers of the five roadway-pricing programs listed above. The objective of these meetings was to explore how the programs were created, how they were implemented, and what lessons were learned. To obtain this information, questions were asked about program initiation, stakeholder engagement, program implementation, revenue allocation, and planning goals and process about how the program addressed the equity concerns of disadvantaged populations. The five interviews are briefly described below with detailed excerpts available in Appendix B.

Between 2015 and 2023, TNP location data has showed an increase of TNP trips in Chicago, particularly in the Chicago downtown area.3 Between March 2018 and February 2019, one-half of all TNP trips in Chicago began and/or ended in the downtown area and nearly one-third of those trips began and ended in the downtown area. In 2018, there were more than 100 million TNP trips in Chicago, and that number has grown significantly since. This rapid increase in TNP trips has resulted in more congestion and emissions and contributed to a decrease in transit ridership in the downtown area.4

Lori Lightfoot, the Mayor of Chicago from 2019 to 2023, proposed that a surcharge of $1.75 ($5.00 for special zones) 5 be imposed on TNP trips that either drop-off or pick up in designated neighborhoods in Chicago.6 The pricing structure was determined by the City of Chicago staff in coordination with local politicians. The cordon-style roadway-pricing program was passed by the Chicago City Council in 2019. That year, this program produced $200 million in revenue, $16 million of which went towards the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA). The remaining revenue was allocated towards the general funds for the City of Chicago. Although TNP companies lobbied to drop the surcharge after the COVID-19 pandemic, they were not successful. TNP location data still shows rapid expansion of TNP trips, and the program has not reduced congestion significantly. TNP data shows that a higher surcharge would be required to significantly reduce congestion based on this policy. The City of Chicago is interested in raising the surcharge, but this action would require significant political support.

In the early 2000s, the I-394 Express Lane Community Task Force was formed and tasked with understanding how pricing programs work and communicating their benefits to the public and elected officials. This task force displayed a grasstops advocacy approach by assembling high-level legislators, city officials, MPO staff, public county officials, Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) officials, MnDOT staff, and other stakeholders. Through detailed technical work and communication of the findings by the task force, the state legislature introduced legislation authorizing MnDOT and the Metropolitan Council, which serves as the MPO for the Minneapolis-Saint Paul metropolitan region, to study and implement congestion pricing and the conversion of an underutilized HOV lane on I-394 into a HOT lane.

The cost of the first phase of the I-394 HOT lane in 2005 was $10 million. Subsequent phases of the program consisted of conversions of HOV lanes to HOT lanes and the addition of new lanes as HOT lanes to manage congestion, which cost $130 million and was financed through an Urban Partnership Agreement grant from the FHWA.

By statute, excess revenues (after capital, operations, and maintenance costs) must be used for the corridor (50 percent of excess revenue) and for transit enhancements (remaining 50 percent). After implementation, 60 percent of the public supported this program, according to the Minnesota Department of Transportation. An after-study by the University of Minnesota showed that commuters on these corridors come from diverse income levels and racial backgrounds.

In 2017, the idea of congestion pricing in Manhattan was revived after previous consideration due to budget shortfalls and the need to generate revenue for transportation improvements. In 2019, the congestion-pricing program was approved by the State of New York through the state budget and has since been approved by the FHWA in 2023. The current target year for implementation of this program is 2024.

The three sponsors for the program are the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA, the lead agency), New York State Department of Transportation, and New York City Department of Transportation. The FHWA was a key collaborator in the development of this program. The Environmental Assessment mentioned several equity concessions, including discounts and scenarios for various toll rates, however, the toll rates have not yet been determined.

In the current proposed version of this congestion-pricing program, motor vehicles that travel south of 60th Street in Manhattan will be charged a toll. The toll rate has not been finalized but is expected to be between $9 and $23 during weekday peak times. A Traffic Mobility Review Board (TMRB), which includes the Director of Planning for New York City and various business leaders in the New York metropolitan region, will recommend toll rates and discounts to the MTA Board. The MTA Board will have the final say on the tolling policy. State tax credits will be available for households making less than $60,000. Tolls will not be required from vehicles with qualifying disabled plates or qualifying transit and emergency vehicles, and passenger vehicles will only be tolled once each day. The TMRB also recommends credits, discounts, and/or exemptions for tolls paid the same day on bridges and tunnels and for some types of for-hire vehicles. The program is designed and projected to raise $1 billion annually and a portion of the revenue will be allocated towards MTA transit infrastructure (capital projects). A key challenge is determining the toll rate, as more discounts will require a higher toll, which would make it more difficult to obtain political buy-in. The implementation of this program has come with resistance from New Jersey, which is currently suing New York to prevent this program from beginning.

The Bay Area Express Lanes concept was driven by environmental concerns in the 1990s. These concerns led to state legislation allowing regional transportation agencies, in cooperation with the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), to apply to the California Transportation Commission to develop and operate HOT lanes, including the administration and operation of a value-pricing program and exclusive or preferential lane facilities for public transit. The Bay Area Express Lanes were constructed under this bill beginning in 2010.

The Bay Area Express Lanes program was included in the regional transportation plan that was published in 2009. In the following years, the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC), San Francisco area’s MPO, converted several existing HOV lane facilities to express toll lanes. Caltrans owns the freeways, but the MTC is responsible for collecting tolls and maintaining the express lanes. Although toll revenue can be used for transportation improvement projects, generating revenue to fund public transportation improvements was not an explicit goal of the program.

The Chinatown/Penn Quarter Parking program began in 2014 as a pilot program in the Chinatown/Penn Quarter Neighborhood of Washington, DC. In this program, fixed-rate, on-street parking was converted to variable-rate parking, depending on parking demand. In 2019 the pilot program became permanent.

The District Council approved city-wide legislation that permitted the demand-parking pricing in 2012. The legislation allowed flexible parking-pricing policies to consider smart technologies, growing availability of travel and parking data, and socioeconomic factors to effectively transform curbside spaces and control demand. In addition, the FHWA Value Pricing Pilot Program provided funding for the program that allowed district officials to kick off the program in 2014.

This program was asset-light and monitored parking demand on a block-by-block basis, rather than individual spaces. This information is accessible in real time through the ParkDC application, which allows people searching for parking to get a general idea of parking demand in an area, helping them to decide whether to search for on street parking or a private parking garage. This program proved to be successful at reducing the time needed to find a parking space and reducing congestion.8 In addition to helping reduce congestion, the program reduced double parking, provided more efficient curbside uses, and improved safety. Revenue generated from this program is allocated to the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority, which operates the DC Metro as well as program operations.

Although the scope of this study was to focus on roadway pricing examples in the United States, it is important to acknowledge two important congestion pricing programs that are currently in operation internationally: London and Singapore. Both programs are pioneers of roadway pricing and offer important insights that can be applied to potential future roadway-pricing programs.

Roadway pricing in central London began with concerns about worsening congestion, air pollution, and livability problems in the 1990s. It sparked a debate about a roadway-pricing program in central London, which enabled the Greater London Authority Act in 1999, authorizing the mayor and the city transportation department to implement roadway pricing strategies.

On February 17, 2003, a roadway-pricing program began in central London. There was initial opposition to the program from politicians, businesses, trade unions, local media, and the public. However, the public eventually accepted the program, which has significantly reduced traffic congestion, improved air quality, and led to sustainable transportation and a healthier environment.9 Public acceptance has increased over time because environmental and climate issues have become more prominent in recent decades.

The program runs from 7:00 AM to 6:00 PM on weekdays and from 12:00 PM to 6:00 PM on weekends, and the charge is currently £15.00 (approximately $19.00 as of December 2023). Residents in the charging zone receive a 90 percent discount while buses, taxis, and electric cars, and drivers with disabilities are exempted.

Keys to the successful implementation of the program included

In a recent New York Times article about congestion pricing in three cities, London, Singapore, and Stockholm, the authors pointed out that the early successes in the London congestion pricing program have been declining in recent years and congestion has increased to prepandemic levels, resulting in gridlock and air pollution.10 They attributed this congestion not only to the rise in trips involving taxis, Ubers and other ride-hailing vehicles, and delivery trucks, but also to the installation of bus lanes and bike lanes, which took road space from automobiles. Since inception, the London congestion charges have risen from $6.30 to $19.00 today and public support has reduced slightly, but the program reduced traffic and delays and created favorable conditions to attract drivers back. The authors concluded that to realize long-term reduction in congestion, there would need to be a significantly high charge, and this may not lead to public and political support.

Area Licensing Scheme (ALS) is the name of the congestion pricing program that has operated in Singapore since 1975.11 ,12 ALS began as a basic program where drivers were charged a fee to enter a district each day in the AM peak period. For the first 20 years of ALS, vehicles displayed a sticker on their windshield, which indicated that the fee to enter the cordon was paid. Currently, an electronic tolling collection (ETC) with gantries that communicate with transponders is used. The tolls range from $0 to $6.71, depending on the time of day. Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) technology is being considered for the ALS program in the future. This program was successful, as it reduced congestion by 20 percent initially. Over the years, this success has been maintained through adjustments such as changes to the restricted zone and accounting for vehicles that enter the zone multiple times.

Keys to the successful implementation of the program included

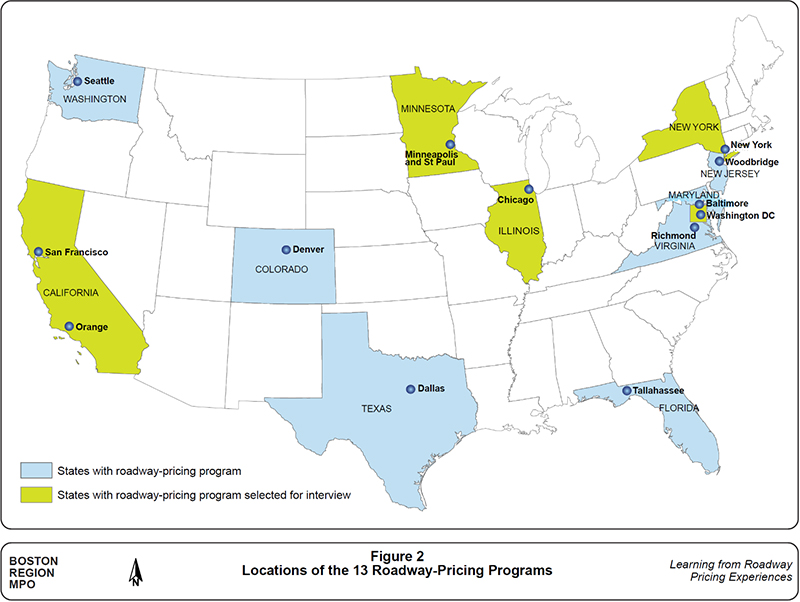

The following challenges of roadway pricing were identified through interviews with the five peer agencies:

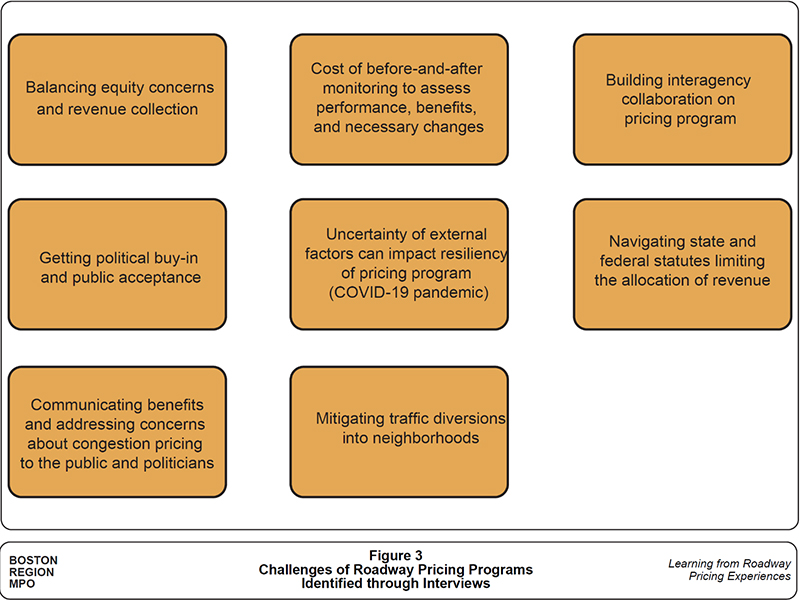

Figure 3 presents the challenges of roadway-pricing programs gathered through interviews with the five peer agencies.

Figure 3

Challenges of Roadway-Pricing Programs Identified through Interviews

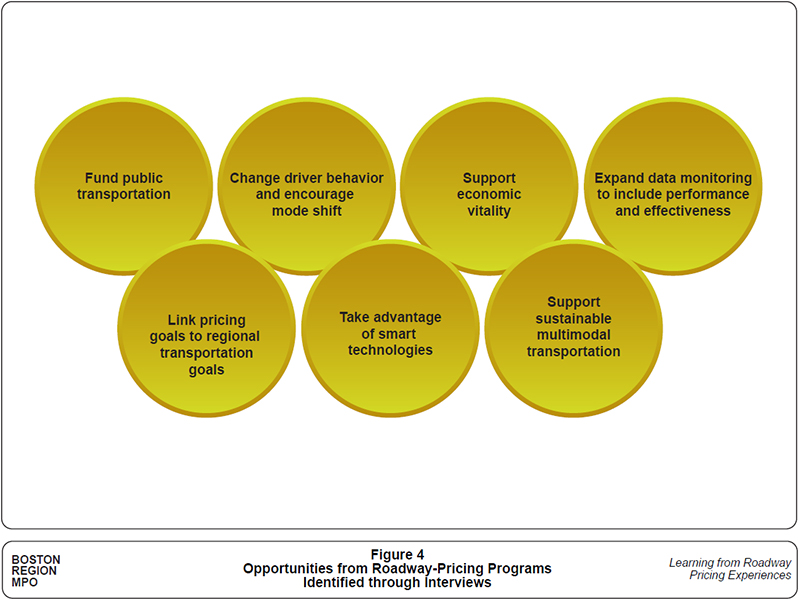

The following opportunities of roadway pricing were identified through interviews with the five peer agencies:

Smaller programs, such as parking pricing, TNP surcharge, or HOV- to HOT-lane conversion programs, can help raise revenue for transit projects. For example, a transportation project such as a new rapid transit line or a bicycle path give commuters a day-one travel alternative to a congested location if a cordon-pricing program is planned in the future. The City of Chicago allocates a portion of the revenue from the TNP surcharge program to the Chicago Transit Authority for transit improvements and some of the remaining revenue for improving active transportation improvements (sidewalks, bike lanes, and pedestrian safety). In addition, the District of Columbia allocates a part of the revenue from its parking program to the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority. Also, early equity studies can be conducted that will provide new data about the potential impacts of a proposed program, which can be used to make decisions about roadway pricing, which can potentially show the before and after impacts of roadway pricing to equity communities.

Figure 4 shows the key opportunities identified during the five interviews.

Figure 4

Opportunities of Roadway-Pricing Program Identified through Interviews

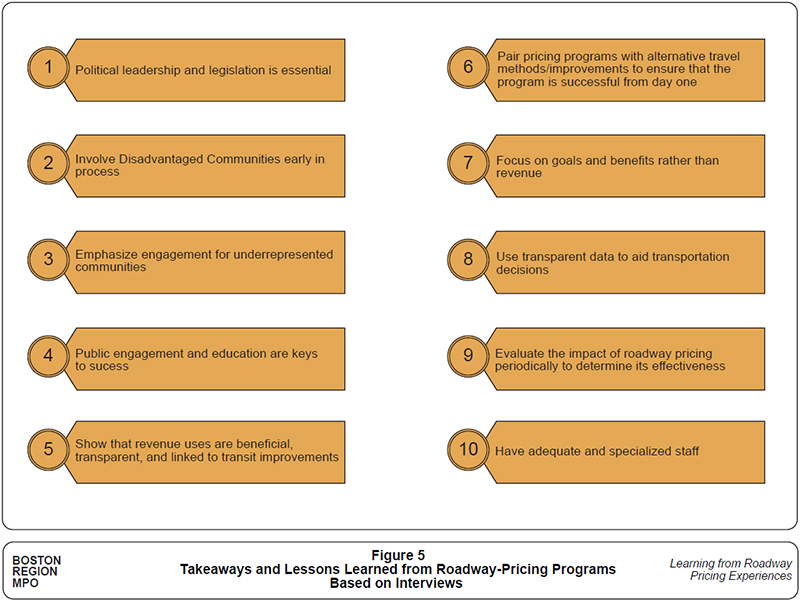

Figure 5 shows the takeaways and lessons learned from peer agency interviews.

Figure 5

Takeaways and Lessons Learned from Roadway-Pricing Programs Based on Interviews

The CMP Committee meeting on August 17, 2023, provided a forum to discuss the MPO’s goals and potential roadway-pricing program in the Boston region. Six of the eight members of the CMP Committee attended the workshop. Two questions were used to guide the discussion:

Below is a synopsis of the discussion in response to these two questions.

The committee felt that all goals proposed at the meeting related to roadway pricing—supporting economic growth, supporting mobility and reliability, supporting transportation-disadvantaged communities, supporting congestion reduction and mode shifts, and supporting transit and other modes—were interrelated and important objectives for a roadway-pricing policy in the Boston region. The committee agreed that economic growth is strongly related to relieving congestion and the other goals identified. For example, if investments are made to provide more transportation options for disadvantaged communities as part of the roadway-pricing strategy, then it increases the potential for human productivity and assists the economy.

The committee recommended that any roadway-pricing strategy should provide disadvantaged communities with more transportation options to help the economy and improve the quality of life of people living in these communities by increasing access to important destinations. In addition, if traffic decreases in these communities because of roadway pricing, they would benefit from reduced congestion and air quality.

The committee suggested that roadway pricing should be implemented to reduce congestion through changes in travel behavior and shifts in travel modes to transit and active transportation.

According to the committee, roadway pricing fits most of the LRTP goals and produces revenue to invest in other modes. Roadway pricing revenues can support improvements in transit services, bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure, and other options. Such improvements could lead to mode shifts, reduce congestion, and improve air quality.

At the CMP Committee workshop on August 17, 2023, MPO staff sought feedback from the committee on what kinds of efforts staff can explore in a future planning process. The discussion was framed around three questions included in the sections below.

What would your priorities be on early communication and engagement with the public about roadway pricing? What forms of communication channels would be appropriate?

The committee recommended that staff start early communications and engagement about roadway pricing with the Regional Transportation Advisory Council, the eight MPO subregional committees, and the MPO-Metropolitan Area Planning Council forums. In addition, the committee suggested that staff engage with equity communities early in the research process to understand priorities and concerns, especially given the recommendations of other regions. The committee also raised the importance of engaging politicians early, even before a potential bill is drafted, in a setting that is comfortable for them. Once these stakeholders are engaged, staff could expand these efforts to include other focus groups.

What would your priorities be on exploring the effects of roadway pricing on equity populations in the Boston region?

The committee stated that critics of roadway-pricing programs often say that it is inequitable because it makes it harder for low-income populations to travel to work and perform basic services. Another possible negative effect of roadway pricing on disadvantaged communities could include traffic diversions through neighborhoods. The committee noted that if the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) is operating at capacity and cannot support additional travelers shifting to transit, then a roadway-pricing strategy is just raising revenue and reducing commuting options for people who want to shift to transit. The committee suggested that there must be expanded and reliable transit services to accommodate mode shift, as well as other travel options or people cannot choose to shift to transit. Ideally, roadway pricing should occur either in coordination or after improvements to the other travel options to absorb mode shifts. They suggested evaluating

How would you like roadway pricing to be incorporated into future long-range transportation plans?

The committee recommended that MPO staff should first evaluate roadway pricing with the regional travel demand model to evaluate the benefits and impacts that arise from implementing roadway pricing strategies. The San Francisco Express Lanes and the New York City Central Business District Tolling Programs have used regional planning models to do various environmental assessments. Early assessments should ensure that a roadway-pricing strategy evaluates the potential to

The Boston Region MPO’s travel demand model (TDM 23) has the capability to conduct these kinds of evaluations. Additional tools may be needed to use model outputs to perform benefit/cost analysis. These assessments, including others not listed above, may provide useful information about using pricing strategies to support LRTP goals and to answer questions that may arise from decision-makers.

This study identified several roadway pricing strategies that could be suitable for the Boston region, pending additional analysis. An initial analysis of 15 roadway-pricing programs (including two international programs), with detailed interviews about five projects, has informed MPO staff and the CMP committee and provided information on the challenges, opportunities, and lessons learned from these programs. The five interviews and the two workshops have provided information on elements needed to implement a successful roadway-pricing program, potential MPO goals for roadway-pricing strategies, and steps to be taken to begin exploring roadway pricing in the MPO planning process.

The following sections describe steps that could be taken to advance the idea of roadway pricing in the Boston region to help relieve congestion. These next steps include activities that could be taken by the MPO and other regional partners. The final presentation of this memorandum to the Boston Region MPO provides the opportunity for a forum to discuss the next steps for this research and advancing potential roadway pricing policies.

The Boston region MPO’s role in implementing the 3C process (continuing, cooperative, and comprehensive) in the region, developing the LRTP (and Transportation Improvement Program [TIP]), and making decisions about where federal funds are spent is important and could influence roadway-pricing programs in the region. The MPO board could direct staff to develop potential policy frameworks and action plans to advance their goals for congestion pricing in the context of other statewide roadway pricing proposals and proposed bills. This would set the stage to incorporate roadway pricing into MPO planning processes such as the early communication and engagement process, follow-up studies on transportation equity issues, linking the LRTP and roadway pricing, and using TDM 23 to explore potential roadway pricing strategies and help answer strategies on travel behavior. In addition, it will be imperative for the MPO to fulfill the 3C process in the Boston region, while executing decisions about where federal funds are spent through the TIP.

Recommended follow-up studies that could be funded through the Boston Region MPO’s existing programs or as discrete projects include

It will be imperative that disadvantaged communities are involved from the beginning. Surveys and meetings should occur to make sure opinions are heard. Careful attention should be given to equity, to prevent a roadway pricing project from being a burden on disadvantaged populations. An extensive framework will need to be mapped including a plan to protect disadvantaged populations as part of the roadway pricing implementation.

Cohesion will need to occur with efforts conducted by several entities being completed around Massachusetts pertaining to roadway pricing. For the implementation of roadway pricing to be successful, there should be an inventory of potential stakeholders in the region who will determine what this program will entail. Once listed, these stakeholders can either be interviewed or surveyed to seek their position and knowledge on roadway pricing. This will indicate who is supportive and who is against roadway pricing as well as who has power and influence. Then, establish a stakeholder working group to help direct how to proceed with further study of roadway pricing, the type of pricing program, what facilities to include/exclude, how to study the equity impacts, etc. Other topics MPO staff could study would include identification of revenue sources to provide transportation alternatives to the priced facilities, and assessment of the implementation costs. Potential regional stakeholders include state departments of transportation, transit operators, local communities, and organizations representing disadvantaged communities.

There are several possible options for roadway pricing in the Boston region. Roadway pricing strategies that fit the Boston region context will need to be explored and plans for implementation will need to be determined. An example of a long-term implementation plan could include creating a small roadway-pricing program, such as a parking-pricing program or TNP surcharge program to raise revenue to fund a bigger roadway-pricing program later, which will include the need to fund a day-one transportation alternative for a final program. Another alternative example would be to seek bonds or other funding to implement a roadway-pricing program, with the promise that the tolls and revenue will eventually pay the bonds over time.

Analysis will need to be done that will specifically pertain to the Boston region. Modeling will need to be completed on the agreed upon alternatives. The Boston Region MPOs TDM 23 model can be used to help understand the impacts of an implemented roadway-pricing program. Both physical attributes such as a cordon-pricing scheme and policies such as taxation or surcharges should be modeled.

It will be important to identify the areas or corridors that would most benefit from roadway pricing in the region. An analysis of congested locations can be done across the region to see where roadway pricing might be able to help. TDM23, in tandem with other tools, could be used to perform the analysis and information from the analysis could guide the MPO board to make informed decisions about future roadway pricing in the Boston region. In addition, strategies will need to be related to the presence and type of congestion as well as transportation equity and available alternatives to driving in the region.

1 INRIX Global Traffic Scorecard, accessed September 25, 2023. https://inrix.com/scorecard/#city-ranking-list

2 Learning from Roadway-Pricing Experiences, Work Program to the Boston Region MPO, January 26, 2023.

3 By law, TNP companies operating in the City of Chicago are required to register with the City and share trip location data.

4 City of Chicago, Transportation Network Providers and Congestion in the City of Chicago, accessed September 25, 2023. www.chicago.gov/content/dam/city/depts/bacp/Outreach%20and%20Education/MLL_10-18-19_PR-TNP_Congestion_Report.pdf

5 Business Affairs and Consumer Protection, City of Chicago Congestion Pricing, accessed September 25, 2023. https://www.chicago.gov/city/en/depts/bacp/supp_info/city_of_chicago_congestion_pricing.html

6 The TNP surcharges applies to two zones: the downtown zone and special zones (airports, Navy Pier, and McCormick Place).

7 The surcharge is dependent on the number riders (single or shared) and the origin and destination of the rider on the trip. Shared trips can have discounts of between 25 and 50 percent depending on the trip origin or destination.

8 Congestion in the Chinatown/Penn Quarter neighborhood decreased at a faster rate than the rest of Washington, DC.

9 Intelligent Transport, “London’s Congestion Charge Celebrates 20 years of Success,” accessed September 25, 2023. https://www.intelligenttransport.com/transport-news/143883/londons-congestion-charge-celebrates-20-years-of-success/

10 Winnie Hu, Ana Ley, Stephen Castle, and Christina Anderson, “Congestion Pricing’s Impact on New York? These 3 Cities Offer a Glimpse,” The New York Times, December 2, 2023, accessed December 2, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/02/nyregion/new-york-congestion-pricing-london-stockholm-singapore.html

11 Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, “How Singapore improved traffic with congestion pricing,” accessed September 25, 2023. https://www.cmap.illinois.gov/updates/all/-/asset_publisher/UIMfSLnFfMB6/content/singapore-congestion-pricing

12 Walter Theseira, Singapore University of Social Sciences, International Transport Forum “Congestion Control in Singapore Discussion Paper,” accessed September 25, 2023. https://www.itf-oecd.org/sites/default/files/docs/congestion-control-singapore.pdf

Appendix A, Table 1

Identifying Roadway-Pricing Programs for Interviews

| Implementing Agency |

Program Description |

Purpose/Goals |

Roadway-Pricing Policy |

Challenges |

Considerations for Incorporating Congestion Pricing in the Planning Process |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Reduce Congestion/ Increase Person Flow |

Improve Air Quality/Reduce GHG/Improve Quality of Life |

Improve Safety |

Improve Reliability / Predictability of Travel |

Generate RevenueA1 |

Support Economic Growth |

|

|

|

|

Cordon Pricing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tri-borough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, Metropolitan Transportation Authority, New York City, New York

|

The Central Business District (CBD) Tolling Program would toll vehicles that enter Manhattan CBD and would include a zone that would cover 60th Street in Manhattan and all the roadways south of 60th Street.

Status: Environmental Assessments completed in August 2022, and it is anticipated to go into operation in 2024. |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

Analysis of

Lessons to be learned from this program include

|

|

Cordon Pricing/Targeted Road User Tolls (TRUT) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

City of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois |

The City of Chicago operates the Transportation Network Providers (TNP) Congestion Pricing. TNPs such as Uber or Lyft, which operate within the designated downtown cordon during peak-period pay surcharges. The designated downtown cordon includes the Chicago Loop, West Loop, South Loop, and the neighborhoods of River North, Streeterville, Near North, Gold Coast, Old Town, and Goose Island.

Status: In operation since 2020. |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

Lessons to be learned include

|

|

Express Lanes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Colorado Transportation Investment Office, Colorado Department of Transportation, Denver, Colorado |

Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) operates and maintain

Status: In operation since 2006, some express lanes are currently in development or construction. |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Stakeholder engagement was a key facet in developing recommendations for a future network of express lanes. The main communication goals were to educate and engage stakeholders and the public on

Lessons to be learned include

|

Bay Area Infrastructure Finance Authority (BAIFA), a unit of the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC), San Francisco, California |

The Bay Area Infrastructure Finance Authority (BAIFA), a unit of the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC), operates and maintains the MTC Bay Area express lanes. The growing Bay Area express lanes network is made up of more than 155 lane-miles, including I-580, I-680 southbound, I-880, State Route 237, US 101, State Route 237, and State Route 85.

Status: In operation since 2010, developing vision and scope for future express lanes network.

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

The MTC Transportation 2035 plan evaluated the HOT lane network with express bus enhancements, regional freeway operational improvements, and regional rail expansion. The evaluation included

MTC also developed a legislative framework for the express lane network that addresses issues such as

MTC carefully framed its public engagement materials (web site, press releases, etc.) on the topic of HOT lanes for the public

Lessons to be learned include

|

Texas Department of Transportation, Dallas, Texas |

The Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) operates and maintains express lanes in the Dallas-Fort Worth area called TEXPRESS lanes. The TEXPRESS network is made up of more than 100 miles on eight roadways including I-35E, I-30, SH 114, I-635E, SH 183, and LOOP 12. TxDOT has several public-private partnerships (P3) with the LBJ Infrastructure Group, NTE Mobility Partners, and NTE Mobility Partners Segments 3.

Status: In operation since 2015, some projects are currently in construction or development. |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Lessons to be learned include the benefit of building

|

Virginia Department of Transportation, Richmond, Virginia |

The Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) partnered with Transurban to create faster travel options including the express lanes on I-495, I-95 and I-395. VDOT operates the express lanes on I-66 inside the Beltway. The I-66 Express Mobility Partners operates and maintains the I-66 express lanes outside of the Beltway in a public-private partnership with VDOT.

Status: In operation since 2012, some projects are in development. |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Lessons to be learned include

|

The Orange County Transportation Authority, Orange, California |

The Orange County Transportation Authority (OCTA) and Riverside County Transportation Commission (RCTC) operate and maintain the California State Route 91 (SR 91) express and I-405 express lanes.

Status: In operation since 1995, some express lanes are in construction or development.

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

Lessons to be learned from OCTA Express Lanes include

|

Washington State Department of Transportation, Seattle, Washington |

Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) operates and maintains toll roads and bridges in the state. WSDOT's toll facilities include I-405 express lanes, SR 167 HOT lane, SR 520 Bridge tolling, SR 99 Tunnel tolling, and the Tacoma Narrows Bridge tolling.

Status: In operation since 2011, some express lanes are in development. |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

A comprehensive tolling study that

A traffic choices study that examined how travelers change their travel behavior (number, mode, route, and time of vehicle trips) in response to time-of-day variable charges in a congestion pricing program. Using behavioral information to feed travel demand models for better analysis of road pricing.

Treating pricing as an integral part of regional transportation plan development was important to the success of the Puget Sound Regional Council process.

Lessons to be learned include

|

Florida Department of Transportation, Tallahassee, Florida |

The Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) operates and maintains express lanes on several high-traffic areas throughout the state, such as on I-295 in Jacksonville, I-595 in Broward county, I-75 and I-95 in Miami-Dade and Broward counties, I-4 Ultimate and Beachline Expressway in Orlando, and Veterans Expressway in Tampa.

https://www.fdot.gov/traffic/teo-divisions.shtm/cav-ml-stamp/managedlanes.shtm

Status: In operation since 2014, some express lanes are in development. |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

Lessons to be learned include

|

Maryland Transportation Authority, Baltimore, Maryland |

Maryland Transportation Authority operates and maintains the I-95 Express Toll Lanes (I-95 ETL). There are currently two express toll lanes in addition to three to four toll-free general-purpose lanes in both directions. I-95 ETL Northbound Extension is a planned extension of the existing express toll lanes. There will be transit connections at the proposed park-and-ride facilities.

https://mdta.maryland.gov/ETL/I-95_ExpressTollLanes.html

Status: In operation since 2015. The full extension of this project is under construction and will be completed in 2027. |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Roadway pricing is incorporated into Baltimore Metropolitan Council's Long-Range Transportation Plans and Transportation Improvement Program (TIP). The MPO holds public meetings to take comments on the TIP amendments for new Express Toll Lane program.

Lessons to be learned include

|

|

Variable Pricing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The New Jersey Turnpike Authority, Woodbridge, New Jersey |

The New Jersey Turnpike opened in 1951. The current length of the New Jersey Turnpike mainline expressway is 117 miles. Variable pricing began in the fall of 2000. This enabled a discount to travelers who use the facility during off-peak hours and use an EZ-Pass.

https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/policy/otps/vpqrrt/sec5.cfm

Status: Variable rate pricing has been in operation since 2000.

|

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

Lessons to be learned include

|

|

HOT Lanes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Minnesota Department of Transportation, St. Paul, Minnesota |

The Minnesota Department of Transportation operates and maintains the E-ZPass HOT Lanes. Minnesota’s HOT lane system includes I-35E, I-35W South Metro, I-35W North Metro, and I-394.

https://www.dot.state.mn.us/ezpassmn/howezpassworks.html

Status: In operation since 2005. |

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

Pricing is one of the five “key components” of the Twin Cities’ Long-Range Plan to cope with “limited resources” and is cast as fully consistent with stated transit and HOV strategies.

Lessons to be learned include

|

|

Parking and Curb Management Pricing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

District Department of Transportation, Washington, District of Columbia |

The District Department of Transportation operates the Penn Quarter/Chinatown Parking Pricing Pilot program. The program was implemented to better connect parking availability with demand by providing real-time parking information to motorists.

https://dc.gov/release/dc-prepares-launch-new-parking-program-downtown

Status: In Operation since 2016, expansion under consideration.

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

None |

The nature of curbside use is changing considerably and the demand for that use is changing considerably. Demand-based parking could lead to important safety outcomes by reducing double parking and blocking bike lanes and crosswalks.

Lessons to be learned include

|

GHG = greenhouse gas. HOT = high-occupancy toll lane. HOV = high-occupancy vehicle lane. HOV 2+/3+ = vehicles with 2/3 persons in high-occupancy vehicle lane.

A1 Uses of the revenue generated varied and included funding transportation improvements and providing travel choices; maintaining and preserving infrastructure; promoting transportation equity; promoting sustainable modes of transportation; supporting public transit; and making shared rides affordable in transportation equity neighborhoods.

Appendix A, Table 2

Identifying Roadway-Pricing Programs for Interviews

| Implementing Agency/Location |

Program Name |

Roadway Pricing Type |

Purpose/Goals |

Criteria for Selecting Program for Interviews |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Reduce Congestion/ Increase Person Flow |

Improve Air Quality/ Improve Quality of Life |

Improve Safety |

Improve Reliability/ Predictability of Travel |

Generate RevenueA2 |

Support Economic Growth |

Opportunity to Learn from Challenges |

Program Goals Align with the Boston MPO Planning Process |

Ease of Implementing in the Boston RegionA3 |

Program was Recommended by Workshop Participants |

Environmental Assessment Completed before Implementation |

Program Directly Addresses Equity Concerns |

Total Points |

Tri-Borough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, Metropolitan Transportation Authority, New York City, New York |

Central Business District Tolling Program |

Cordon Pricing |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

6 |

City of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois |

Chicago’s Transportation Network Provider Congestion Pricing |

Cordon Pricing/Targeted Road User Tolls (TRUT) |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

4 |

Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT), Denver, Colorado |

FDOT’s Express-Lanes Program |

Express Lanes |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

3 |

Bay Area Infrastructure Finance Authority (BAIFA) / Metropolitan Transportation Commission, San Francisco Bay Area, California |

Metropolitan Transportation Commission’s Express-Lanes Program |

Express Lanes |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

4 |

Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT), Dallas, Texas |

TxDOT’s Express-Lanes Program |

Express Lanes |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

4 |

Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), Northern Virginia/Washington DC Suburbs |

VDOT’s Express-Lanes Program |

Express Lanes |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

3 |

The Orange County Transportation Authority, Orange County, California |

Orange County Transportation Authority’s Express-Lanes Program |

Express Lanes |

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

3 |

Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT), Seattle, Washington |

WSDOT’s Express-Lanes Program |

Express Lanes |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

3 |

Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT), Tallahassee, Florida |

FDOT’s Express-Lanes Program |

Express Lanes |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

3 |

Maryland Transportation Authority, Baltimore, Maryland |

Maryland Transportation Authority’s Express-Lanes Program |

Express Lanes |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

3 |

The New Jersey Turnpike Authority, New Jersey |

New Jersey Turnpike Variable Rate Pricing

|

Variable Pricing |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

4 |

Minnesota Department of Transportation (MnDOT), St. Paul/Minneapolis, Minnesota |

MnDOT’s E-ZPass Express Lanes Program |

HOT Lanes |

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

4 |

District Department of Transportation, Washington, District of Columbia |

Penn Quarter/Chinatown Parking Pricing Program, Washington, DC |

Parking and Curb Management Pricing |

X |

X |

|

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

4 |

GHG = greenhouse gas. HOT = high-occupancy toll lane. HOV = high-occupancy vehicle lane. HOV 2+/3+ = vehicles with 2/3 persons in high-occupancy vehicle lane

A2The light green highlighted rows are the programs selected for interviews.

Uses of the revenue generated varied and included funding transportation improvements and providing travel choices; maintaining and preserving infrastructure; promoting transportation equity; promoting sustainable modes of transportation; supporting public transit; and making shared rides affordable in transportation equity neighborhoods.

A3 Ease of implementation include pricing programs that are low cost, does not involve widening or add lane miles or major changes to the highway system.

Background

In 2019, Lori Lightfoot, who was the Chicago mayor at the time, proposed that a surcharge of $1.75 ($5.00 for special zones) be imposed on Transportation Network Provider (TNP) trips that either drop-off or pick up in designated neighborhoods in Chicago. This cordon style roadway pricing program was passed by the Chicago city council in 2019.

Federal and State Support

There wasn’t much federal and state involvement with the implementation of this program.

Program Goals

Revenue and Operating Costs

Revenue Background

Fee Structure Goals

Costs and Operations

Challenges

Opportunities

Using Data to Manage TNP’s

As of 2019, TNP data was collected at the census block level. Since then, Chicago has been able to receive even more detailed data. At first, Chicago couldn’t obtain the through points, just the beginning and end points of a trip. Now Chicago is receiving more frequent pings to make the routes visible.

Planning Process

Chicago staff sat down with transportation and civil organizations to inform them that they want to implement this program and warned about the challenges ahead.

Equity

Reducing the cost of shared rides that did not go downtown is a big priority. An objective is to shift congestion to neighborhoods that have roadways that are underutilized. Revenue from this program goes to support public transit investments at the CTA which helps address equity concerns. Chicago also uses revenue to invest in shared bicycles.

Keys to a Successful Program

Communication and Messaging

Expanding the TNP Surcharge

Background

Interest in congestion pricing started in the early 1990s when MnDOT and the Metropolitan Council began to study and implement congestion pricing.

Federal and State Support

Enabling State Legislature

Public and political work in the early 1990s led to a state enabling legislature allowing the MnDOT and the Metropolitan Council to study and implement congestion pricing. In early 2000, a Value Pricing Advisory Task Force comprising state legislators and city officials and the I-394 Express Lane Community Task Force were formed and tasked with communicating benefits and understanding of the pricing project to the public. The task force visited SR 91 Express Lanes in California, which is using pricing to maximize capacity and maintained advantage for buses and carpools. The efforts led to the introduction of state legislation authorizing the conversion of underutilized High Occupancy Lane (HOV) lane into HOT Toll Lane.

Federal Support

The Federal Value Pricing Pilot Program supported the I-394 HOV to HOT conversion in 2005. The project received $10 million federal demonstration grants and regular MnDOT funds. This low-cost conversion project involved installing tolling equipment for the contraflow lane.

Program Goals

Revenue

Challenges

Opportunities

Communication and Messaging

Expanding the Express Lanes

Background

In 2006, the city of New York proposed to implement congestion pricing in Manhattan Central Business District (CBD). This congestion pricing program was approved by the City but was rejected by New York State. Since the congestion pricing bill failed to pass in 2008, this program was shelved until 2017.

In 2017, the idea of congestion pricing in Manhattan was revived due to budget shortfalls and revenue needed for transportation repairs. In 2019, the congestion pricing program was approved by New York State through the state budget and has since been approved by the FHWA, in 2023. The current target year for implementation of this program is 2024.

In the current version of this congestion pricing program, motor vehicles that travel south of 60th Street will be charged a toll. The toll rate hasn’t been determined yet, but the final set rate will be between $9 and $23.

Federal and State Support

Program Goals

Revenue and Operating Costs

Revenue Background

Costs and Operations

Challenges

Opportunities

Planning Process

Traffic Mobility Review Board (TMRB)—this is a six-member panel that will implement the tolling structure. The MTA and FHWA must also approve of the tolling structure.

The MTA did not consider adding a new transit project to be implemented before the congestion pricing program begins, because the pandemic caused the drop in ridership on the subway and extra capacity was not needed. Additionally, the model projects that transit ridership will only increase two percent with congestion pricing. However, there are discussions about possibly adding some additional bus rapid transit routes to the system before or shortly after implementation.

Equity

Discounts

Planned Assessments

When implemented, these assessments will be done:

Communication and Messaging

Background of Other Similar Program

New York City TNC surcharge

Federal and State Support

Relevant Assembly Bills

Background

The MTC began implementing the Bay Area Express Lanes network after seeing the California SR 91 express lanes being implemented in Orange County, California, in the late 1990s. The Bay Area Express Lanes network concept was also driven by environmental concerns back in the 1990s. The goal of this program is to increase person throughput and reduce vehicle emissions. The objective was to increase carpooling and manage travel demand of single-occupant vehicles (SOV).

Program Goals

Challenges

Equity Concerns

Operations

Revenue

Environmental Concerns

Environmental advocates express concerns about capacity expansion by adding more lanes for express lanes. MTC is looking at federal rules about converting general purpose lanes to toll lanes than building new toll lanes.

Opportunities

Funding

The Bay Area Express Lanes program did not use public private partnerships, mainly because of federal funding and state propositions to fund transportation improvements.

Keys to Implementation

Takeaways and Lessons Learned

The MTC seeks to implement cost-effective, sustainable, and self-supporting managed lanes that help achieve regional goals.

Background

The DC Penn Quarter Parking program is a pilot program that converted fixed rate, on-street parking to variable rate on-street parking depending on parking demand. This program was implemented in the Chinatown/Penn Quarter Neighborhood. The pilot program began in 2014 and concluded in 2019, at which time the pricing adjustments in the neighborhood became permanent.

Federal and State Support

This program was funded from a grant though the FHWA Value Pricing Pilot Program

Program Goals and Outcomes

Implementation

There were three steps for implementation:

Revenue and Operations

Challenges

Opportunities

Communication and Messaging

Background of Other Similar Programs

The Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) operates its programs, services, and activities in compliance with federal nondiscrimination laws including Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Title VI), the Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1987, and related statutes and regulations. Title VI prohibits discrimination in federally assisted programs and requires that no person in the United States of America shall, on the grounds of race, color, or national origin (including limited English proficiency), be excluded from participation in, denied the benefits of, or be otherwise subjected to discrimination under any program or activity that receives federal assistance. Related federal nondiscrimination laws administered by the Federal Highway Administration, Federal Transit Administration, or both, prohibit discrimination on the basis of age, sex, and disability. The Boston Region MPO considers these protected populations in its Title VI Programs, consistent with federal interpretation and administration. In addition, the Boston Region MPO provides meaningful access to its programs, services, and activities to individuals with limited English proficiency, in compliance with U.S. Department of Transportation policy and guidance on federal Executive Order 13166. The Boston Region MPO also complies with the Massachusetts Public Accommodation Law, M.G.L. c 272 sections 92a, 98, 98a, which prohibits making any distinction, discrimination, or restriction in admission to, or treatment in a place of public accommodation based on race, color, religious creed, national origin, sex, sexual orientation, disability, or ancestry. Likewise, the Boston Region MPO complies with the Governor's Executive Order 526, section 4, which requires that all programs, activities, and services provided, performed, licensed, chartered, funded, regulated, or contracted for by the state shall be conducted without unlawful discrimination based on race, color, age, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, religion, creed, ancestry, national origin, disability, veteran's status (including Vietnam-era veterans), or background. A complaint form and additional information can be obtained by contacting the MPO or at http://www.bostonmpo.org/mpo_non_discrimination. To request this information in a different language or in an accessible format, please contact Title VI Specialist By Telephone: For people with hearing or speaking difficulties, connect through the state MassRelay service:

For more information, including numbers for Spanish speakers, visit https://www.mass.gov/massrelay.

|