Long-Range Transportation Plan 2024

Appendices

Boston Region MPO

Appendix A: About the MPO

Appendix B: MPO Regulatory Framework

Appendix C: Public Engagement and Public Comment

Appendix D: Universe of Projects and Project Evaluations

Appendix E: Determination of Air Quality Conformity and Greenhouse Gas Analysis

Appendix F: Financial Report

Appendix G: Systems Performance Report

Appendix H: Transportation Equity Performance Report

Appendix I: Disparate Impact and Disproportionate Burden Policy

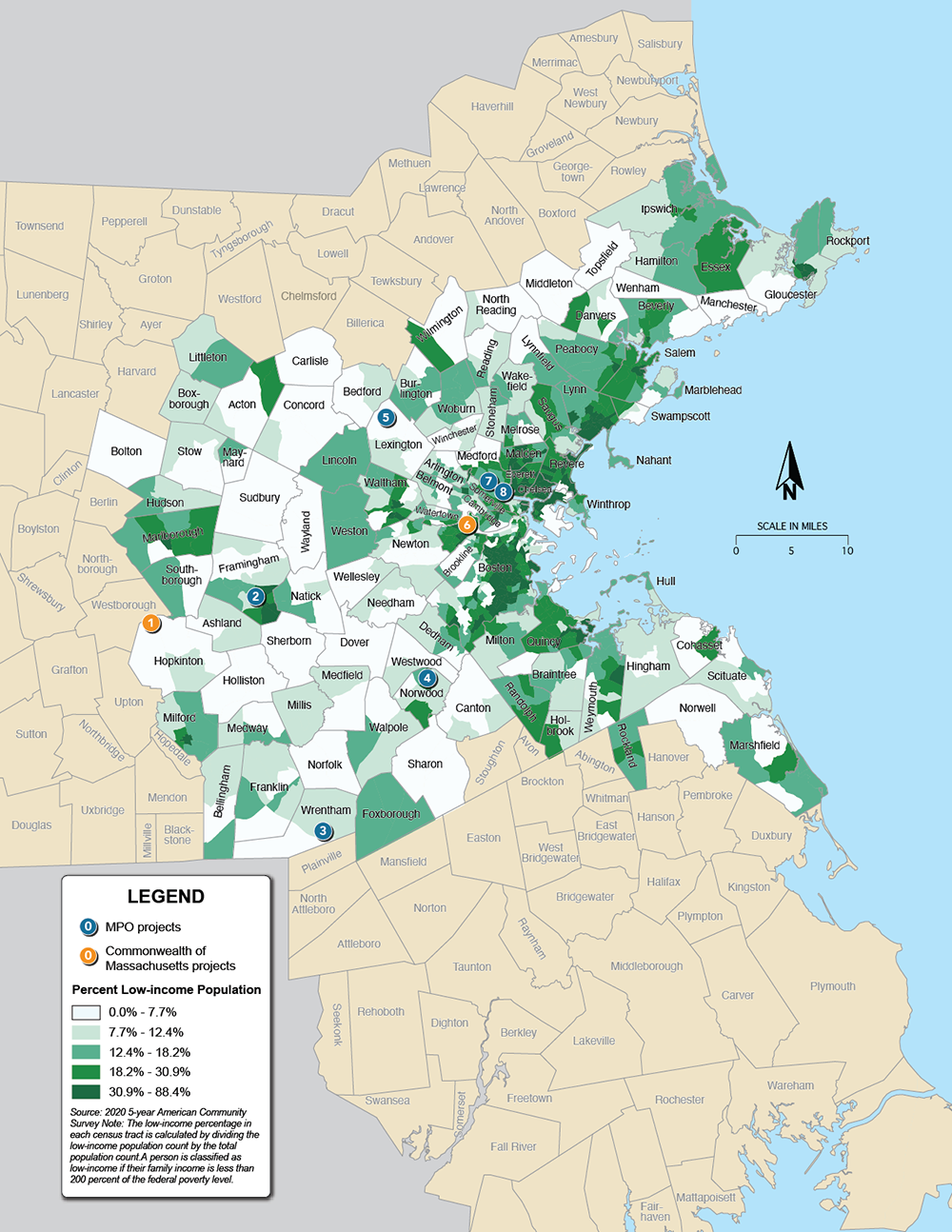

The Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization’s (MPO) planning area covers 97 municipalities from Boston north to Ipswich, south to Marshfield, and west to Interstate 495. Figure A-1 shows the map of the Boston Region MPO’s member municipalities.

Figure A-1

Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization Municipalities

Source: Boston Region MPO.

The MPO’s board has 22 voting members. Several state agencies, regional organizations, and the City of Boston are permanent voting members, while 12 municipalities are elected as voting members for three-year terms. Eight municipal members represent each of the eight subregions of the Boston region, and there are four at-large municipal seats. The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and Federal Transit Administration (FTA) participate on the MPO board as advisory (nonvoting) members. Figure A-2 shows MPO membership and the organization of the Central Transportation Planning Staff (CTPS), which serves as staff to the MPO.

Figure A-2

Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization Member Structure

Source: Boston Region MPO.

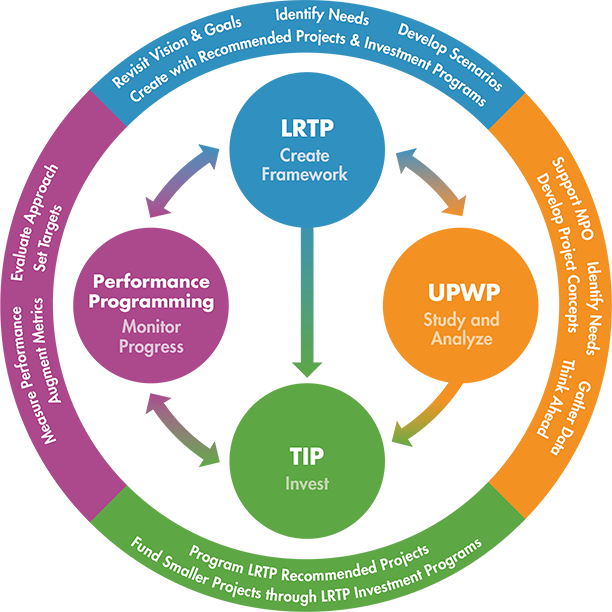

As part of its continuing, comprehensive, and cooperative (3C) planning process, the MPO regularly produces several planning and programming documents that describe MPO priorities and investments. These are collectively referred to as certification documents and are required for the MPO’s process to be certified as meeting federal requirements and, subsequently, to receive federal transportation funds. The three documents that comprise the certification documents are the Long-Range Transportation Plan (LRTP), the Transportation Improvement Program (TIP), and the Unified Planning Work Program (UPWP). In addition to producing these documents, the MPO must also establish and conduct an inclusive public participation process; comply with all federal Title VI, environmental justice, and nondiscrimination requirements; and maintain transportation models and data resources to support air quality conformity determination and long- and short-range planning work and initiatives. The following is a summary of each of the certification documents.

MassDOT was established under Chapter 25of the Acts of 2009, An Act Modernizing the Transportation Systems of the Commonwealth. MassDOT has four divisions: Highway, Rail and Transit, Aeronautics, and the Registry of Motor Vehicles. The MassDOT Board of Directors, composed of 11 members appointed by the governor, oversees all four divisions and MassDOT operations and works closely with the MBTA Board of Directors. The MassDOT Board of Directors was expanded to 11 members by the Legislature in 2015, a group of transportation leaders assembled to review structural problems with the MBTA and deliver recommendations for improvements. MassDOT has three seats on the MPO board, including seats for the Highway Division.

The MassDOT Highway Division has jurisdiction over the roadways, bridges, and tunnels that were overseen by the former Massachusetts Highway Department and Massachusetts Turnpike Authority. The Highway Division also has jurisdiction over many bridges and parkways that previously were under the authority of the Department of Conservation and Recreation. The Highway Division is responsible for the design, construction, and maintenance of the Commonwealth’s state highways and bridges. It is also responsible for overseeing traffic safety and engineering activities for the state highway system. These activities include operating the Highway Operations Control Center to ensure safe road and travel conditions.

The MBTA, created in 1964, is a body politic and corporate, and a political subdivision of the Commonwealth. Under the provisions of Chapter 161A of the Massachusetts General Laws, it has the statutory responsibility within its district of operating the public transportation system in the Boston region, preparing the engineering and architectural designs for transit development projects, and constructing and operating transit development projects. The MBTA district comprises 176 communities, including all 97 cities and towns of the Boston Region MPO area.

The MBTA Advisory Board was created by the Massachusetts Legislature in 1964 through the same legislation that created the MBTA. The Advisory Board consists of representatives of the 176 cities and towns that compose the MBTA’s service area. Cities are represented by either the city manager or mayor, and towns are represented by the chairperson of the board of selectmen. Specific responsibilities of the Advisory Board include reviewing and commenting on the MBTA’s long-range plan, the Program for Mass Transportation; proposed fare increases; the annual MBTA Capital Investment Program; the MBTA’s documentation of net operating investment per passenger; and the MBTA’s operating budget. The MBTA Advisory Board advocates for the transit needs of its member communities and the riding public.

Massport has the statutory responsibility under Chapter 465 of the Acts of 1956, as amended, for planning, constructing, owning, and operating such transportation and related facilities as may be necessary for developing and improving commerce in Boston and the surrounding metropolitan area. Massport owns and operates Boston Logan International Airport, the Port of Boston’s Conley Terminal, Flynn Cruiseport Boston, Hanscom Field, Worcester Regional Airport, and various maritime and waterfront properties, including parks in the Boston neighborhoods of East Boston, South Boston, and Charlestown.

MAPC is the regional planning agency for the Boston region. It is composed of the chief executive officer (or a designee) of each of the cities and towns in the MAPC’s planning region, 21 gubernatorial appointees, and 12 ex-officio members. It has statutory responsibility for comprehensive regional planning in its region under Chapter 40B of the Massachusetts General Laws. It is the Boston Metropolitan Clearinghouse under Section 204 of the Demonstration Cities and Metropolitan Development Act of 1966 and Title VI of the Intergovernmental Cooperation Act of 1968. Also, its region has been designated an economic development district under Title IV of the Public Works and Economic Development Act of 1965, as amended. MAPC’s responsibilities for comprehensive planning encompass the areas of technical assistance to communities, transportation planning, and development of zoning, land use, demographic, and environmental studies. MAPC activities that are funded with federal metropolitan transportation planning dollars are documented in the Boston Region MPO’s UPWP.

The City of Boston, six elected cities (currently Beverly, BurlingtonEverett, Framingham, Newton, and Somerville), and six elected towns (currently Acton, Arlington, Brookline, Hull, Medway, and Norwood) represent the 97 municipalities in the Boston Region MPO area. The City of Boston is a permanent MPO member and has two seats. There is one elected municipal seat for each of the eight MAPC subregions and four seats for at-large elected municipalities (two cities and two towns). The elected at-large municipalities serve staggered three-year terms, as do the eight municipalities representing the MAPC subregions.

The Regional Transportation Advisory Council, the MPO’s citizen advisory group, provides the opportunity for transportation-related organizations, non-MPO member agencies, and municipal representatives to become actively involved in the decision-making processes of the MPO as it develops plans and prioritizes the implementation of transportation projects in the region. The Advisory Council reviews, comments on, and makes recommendations regarding certification documents. It also serves as a forum for providing information on transportation topics in the region, identifying issues, advocating for ways to address the region’s transportation needs, and generating interest among members of the general public in the work of the MPO.

This appendix contains detailed background on the regulatory documents, legislation, and guidance that shape the Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization’s (MPO) transportation planning process.

The Boston Region MPO is charged with executing its planning activities in line with federal and state regulatory guidance. Maintaining compliance with these regulations allows the MPO to directly support the work of these critical partners and ensures its continued role in helping the region move closer to achieving federal, state, and regional transportation goals. This appendix describes all of the regulations, policies, and guidance taken into consideration by the MPO during development of the certification documents and other core work the MPO will undertake during federal fiscal year (FFY) 2024.

The MPO’s planning processes are guided by provisions in federal transportation authorization bills, which are codified in federal statutes and supported by guidance from federal agencies. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), signed into law on November 15, 2021, replaced the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act as the nation’s five-year surface transportation bill, and covers FFYs 2022–26. This section describes new provisions established in the BIL as well as items established under previous bills, such as the FAST Act.

The purpose of the national transportation goals, outlined in Title 23, section 150, of the United States Code (23 USC § 150), is to increase the accountability and transparency of the Federal-Aid Highway Program and to improve decision-making through performance-based planning and programming. The national transportation goals include the following:

The Boston Region MPO has incorporated these national goals, where practicable, into its vision, goals, and objectives, which provide a framework for the MPO’s planning processes. More information about the MPO’s vision, goals, and objectives is included in Chapter 3.

The MPO gives specific consideration to the federal planning factors, described in Title 23, section 134, of the US Code (23 USC § 134), when developing all documents that program federal transportation funds. In accordance with the legislation, studies and strategies undertaken by the MPO shall

The United States Department of Transportation (USDOT), in consultation with states, MPOs, and other stakeholders, established performance measures relevant to the national goals established in the FAST Act. These performance topic areas include roadway safety, transit system safety, National Highway System (NHS) bridge and pavement condition, transit asset condition, NHS reliability for both passenger and freight travel, traffic congestion, and on-road mobile source emissions. The FAST Act and related federal rulemakings require states, MPOs, and public transportation operators to follow performance-based planning and programming practices—such as setting targets—to ensure that transportation investments support progress toward these goals. See Appendix G for more information about how the MPO has and will continue to conduct performance-based planning and programming.

On December 30, 2021, the Federal Highway Administration and Federal Transit Administration jointly issued updated planning emphasis areas for use in MPOs’ transportation planning process, following the enactment of the BIL. Those planning emphasis areas include the following:

The Clean Air Act, most recently amended in 1990, forms the basis of the United States’ air pollution control policy. The act identifies air quality standards, and the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) designates geographic areas as attainment (in compliance) or nonattainment (not in compliance) areas with respect to these standards. If air quality in a nonattainment area improves such that it meets EPA standards, the EPA may redesignate that area as being a maintenance area for a 20-year period to ensure that the standard is maintained in that area.

The conformity provisions of the Clean Air Act “require that those areas that have poor air quality, or had it in the past, should examine the long-term air quality impacts of their transportation system and ensure its compatibility with the area’s clean air goals.” Agencies responsible for Clean Air Act requirements for nonattainment and maintenance areas must conduct air quality conformity determinations, which are demonstrations that transportation plans, programs, and projects addressing that area are consistent with a State Implementation Plan (SIP) for attaining air quality standards.

Air quality conformity determinations must be performed for capital improvement projects that receive federal funding and for those that are considered regionally significant, regardless of the funding source. These determinations must show that projects in the MPO’s Long-Range Transportation Plan (LRTP) and Transportation Improvement Program (TIP) will not cause or contribute to any new air quality violations; will not increase the frequency or severity of any existing air quality violations in any area; and will not delay the timely attainment of air quality standards in any area. The policy, criteria, and procedures for demonstrating air quality conformity in the Boston region were established in Title 40, parts 51 and 53, of the Code of Federal Regulations (40. C.F.R. 51, 40 C.F.R. 53).

On April 1, 1996, the EPA classified the cities of Boston, Cambridge, Chelsea, Everett, Malden, Medford, Quincy, Revere, and Somerville as in attainment for carbon monoxide (CO) emissions. Subsequently, the Commonwealth established a CO maintenance plan through the Massachusetts SIP process to ensure that emission levels did not increase. While the maintenance plan was in effect, past TIPs and LRTPs included an air quality conformity analysis for these communities. As of April 1, 2016, the 20-year maintenance period for this maintenance area expired and transportation conformity is no longer required for carbon monoxide in these communities. This ruling is documented in a letter from the EPA dated May 12, 2016.

On April 22, 2002, the EPA classified the City of Waltham as being in attainment for CO emissions with an EPA-approved limited-maintenance plan. In areas that have approved limited-maintenance plans, federal actions requiring conformity determinations under the EPA’s transportation conformity rule are considered to satisfy the conformity test. The MPO is not required to perform a modeling analysis for a conformity determination for carbon monoxide, but it has been required to provide a status report on the timely implementation of projects and programs that will reduce emissions from transportation sources—so-called transportation control measures—which are included in the Massachusetts SIP. In April 2022, the EPA issued a letter explaining that the carbon monoxide limited maintenance area in Waltham has expired. Therefore, the MPO is no longer required to demonstrate transportation conformity for this area, but the rest of the maintenance plan requirements, however, continue to apply, in accordance with the SIP.

On February 16, 2018, the US Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit issued a decision in South Coast Air Quality Management District v. EPA, which struck down portions of the 2008 Ozone National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) SIP Requirements Rule concerning the ozone NAAQS. Those portions of the SIP Requirements Rule included transportation conformity requirements associated with the EPA’s revocation of the 1997 ozone NAAQS. Massachusetts was designated as an attainment area in accord with the 2008 ozone NAAQS but as a nonattainment or maintenance area as relates to the 1997 ozone NAAQS. As a result of this court ruling, MPOs in Massachusetts must once again demonstrate conformity for ozone when developing LRTPs and TIPs.

MPOs must also perform conformity determinations if transportation control measures (TCM) are in effect in the region. TCMs are strategies that reduce transportation-related air pollution and fuel use by reducing vehicle-miles traveled and improving roadway operations. The Massachusetts SIP identifies TCMs in the Boston region. SIP-identified TCMs are federally enforceable and projects that address the identified air quality issues must be given first priority when federal transportation dollars are spent. Examples of TCMs that were programmed in previous TIPs include rapid-transit and commuter-rail extension programs (such as the Green Line Extension in Cambridge, Medford, and Somerville, and the Fairmount Line improvements in Boston), parking-freeze programs in Boston and Cambridge, statewide rideshare programs, park-and-ride facilities, residential parking-sticker programs, and the operation of high-occupancy-vehicle lanes.

In addition to reporting on the pollutants identified in the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments, the MPOs in Massachusetts are also required to perform air quality analyses for carbon dioxide as part of the state’s Global Warming Solutions Act (GWSA) (see below).

The Boston Region MPO complies with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the American with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA), Executive Order 12898—Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-income Populations (EJ EO), and other federal and state nondiscrimination statutes and regulations in all programs and activities it conducts. Per federal and state law, the MPO does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin (including limited-English proficiency), religion, creed, gender, ancestry, ethnicity, disability, age, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, veteran’s status, or background. The MPO strives to provide meaningful opportunities for participation of all persons in the region, including those protected by Title VI, the ADA, the EJ EO, and other nondiscrimination mandates.

The MPO also assesses the likely benefits and adverse effects of transportation projects on equity populations (populations covered by federal regulations, as identified in the MPO’s Transportation Equity program) when deciding which projects to fund. This is done through the MPO’s project selection criteria. MPO staff also evaluate the projects that are selected for funding, in the aggregate, to determine their overall impacts and whether they improve transportation outcomes for equity populations. The major federal requirements pertaining to nondiscrimination are discussed below.

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 requires that no person be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination on the basis of race, color, or national origin, under any program or activity provided by an agency receiving federal financial assistance. Executive Order 13166—Improving Access to Services for Persons with Limited English Proficiency, dated August 11, 2000, extends Title VI protections to people who, as a result of their nationality, have limited English proficiency. Specifically, it calls for improved access to federally assisted programs and activities, and it requires MPOs to develop and implement a system through which people with limited English proficiency can meaningfully participate in the transportation planning process. This requirement includes the development of a Language Assistance Plan that documents the organization’s process for providing meaningful language access to people with limited English proficiency who access their services and programs.

Executive Order 12898, dated February 11, 1994, requires each federal agency to advance environmental justice by identifying and addressing any disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects, including interrelated social and economic effects, of its programs, policies, and activities on minority and low-income populations.

On April 15, 1997, the USDOT issued its Final Order to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations. Among other provisions, this order requires programming and planning activities to

The 1997 Final Order was updated in 2012 with USDOT Order 5610.2(a), which provided clarification while maintaining the original framework and procedures.

Title III of the ADA “prohibits states, MPOs, and other public entities from discriminating on the basis of disability in the entities’ services, programs, or activities,” and requires all transportation projects, plans, and programs to be accessible to people with disabilities. Therefore, MPOs must consider the mobility needs of people with disabilities when programming federal funding for studies and capital projects. MPO-sponsored meetings must also be held in accessible venues and be conducted in a manner that provides for accessibility. Also, MPO materials must be made available in accessible formats.

The Age Discrimination Act of 1975 prohibits discrimination on the basis of age in programs or activities that receive federal financial assistance. In addition, the Rehabilitation Act of 1975, and Title 23, section 324, of the US Code (23 USC § 324) prohibit discrimination based on sex.

Much of the MPO’s work focuses on encouraging mode shift and diminishing GHG emissions through improving transit service, enhancing bicycle and pedestrian networks, and studying emerging transportation technologies. All of this work helps the Boston region contribute to statewide progress toward the priorities discussed in this section.

Beyond Mobility, the Massachusetts 2050 Transportation Plan, is a planning process that will result in a blueprint for guiding transportation decision-making and investments in Massachusetts in a way that advances MassDOT’s goals and maximizes the equity and resiliency of the transportation system. MPO staff continue to coordinate with MassDOT staff so that Destination 2050 aligns with Beyond Mobility.

The Commission on the Future of Transportation in the Commonwealth—established by Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker’s Executive Order 579—published Choices for Stewardship in 2019. This report makes 18 recommendations across the following five thematic categories to adapt the transportation system in the Commonwealth to emerging needs:

Beyond Mobility will build upon the Commission report’s recommendations. The Boston Region MPO supports these statewide goals by conducting planning work and making investment decisions that complement MassDOT’s efforts and reflect the evolving needs of the transportation system in the region.

The Massachusetts 2023 Strategic Highway Safety Plan (SHSP) identifies the state’s key safety needs and guides investment decisions to achieve significant reductions in highway fatalities and serious injuries on all public roads. The SHSP establishes statewide safety goals and objectives and key safety emphasis areas, and it draws on the strengths of all highway safety partners in the Commonwealth to align and leverage resources to address the state’s safety challenges collectively. The Boston Region MPO considers SHSP goals, emphasis areas, and strategies when developing its plans, programs, and activities.

The Massachusetts Transportation Asset Management Plan (TAMP) is a risk-based asset management plan for the bridges and pavement that are in the NHS inventory. The plan describes the condition of these assets, identifies assets that are particularly vulnerable following declared emergencies such as extreme weather, and discusses MassDOT’s financial plan and risk management strategy for these assets. The Boston Region MPO considers MassDOT TAMP goals, targets, and strategies when developing its plans, programs, and activities.

In 2017, MassDOT finalized the Massachusetts Freight Plan, which defines the short- and long-term vision for the Commonwealth’s freight transportation system. In 2018, MassDOT released the related Commonwealth of Massachusetts State Rail Plan, which outlines short- and long-term investment strategies for Massachusetts’ freight and passenger rail systems (excluding the commuter rail system). In 2019, MassDOT released the Massachusetts Bicycle Transportation Plan and the Massachusetts Pedestrian Transportation Plan, both of which define roadmaps, initiatives, and action plans to improve bicycle and pedestrian transportation in the Commonwealth. These plans were updated in 2021 to reflect new investments in bicycle and pedestrian projects made by MassDOT since their release. The MPO considers the findings and strategies of MassDOT’s modal plans when conducting its planning, including through its Freight Planning Support and Bicycle/Pedestrian Support Activities programs.

The GWSA makes Massachusetts a leader in setting aggressive and enforceable GHG reduction targets and implementing policies and initiatives to achieve these targets. In keeping with this law, the Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs (EEA), in consultation with other state agencies and the public, developed the Massachusetts Clean Energy and Climate Plan for 2020. This implementation plan, released on December 29, 2010 (and updated in 2015), establishes the following targets for overall statewide GHG emission reductions:

In 2018, EEA published its GWSA 10-year Progress Report and the GHG Inventory estimated that 2018 GHG emissions were 22 percent below the 1990 baseline level.

MassDOT fulfills its responsibilities, defined in the Massachusetts Clean Energy and Climate Plan for 2020, through a policy directive that sets three principal objectives:

In January 2015, the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection amended Title 310, section 7.00, of the Code of Massachusetts Regulations (310 CMR 60.05), Global Warming Solutions Act Requirements for the Transportation Sector and the Massachusetts Department of Transportation, which was subsequently amended in August 2017. This regulation places a range of obligations on MassDOT and MPOs to support achievement of the Commonwealth’s climate change goals through the programming of transportation funds. For example, MPOs must use GHG impact as a selection criterion when they review projects to be programmed in their TIPs, and they must evaluate and report the GHG emissions impacts of transportation projects in LRTPs and TIPs.

The Commonwealth’s 10 MPOs (and three non-metropolitan planning regions) are integrally involved in supporting the GHG reductions mandated under the GWSA. The MPOs seek to realize these objectives by prioritizing projects in the LRTP and TIP that will help reduce emissions from the transportation sector. The Boston Region MPO uses its TIP project evaluation criteria to score projects based on their GHG emissions impacts, multimodal Complete Streets accommodations, and ability to support smart growth development. Tracking and evaluating GHG emissions by project will enable the MPOs to anticipate GHG impacts of planned and programmed projects. See Appendix E for more details related to how the MPO conducts GHG monitoring and evaluation.

On September 9, 2013, MassDOT passed the Healthy Transportation Policy Directive to formalize its commitment to implementing and maintaining transportation networks that allow for various mode choices. This directive will ensure that all MassDOT projects are designed and implemented in ways that provide all customers with access to safe and comfortable walking, bicycling, and transit options.

In November 2015, MassDOT released the Separated Bike Lane Planning & Design Guide. This guide represents the next step in MassDOT’s continuing commitment to Complete Streets, sustainable transportation, and the creation of more safe and convenient transportation options for Massachusetts residents. This guide may be used by project planners and designers as a resource for considering, evaluating, and designing separated bike lanes as part of a Complete Streets approach.

In Destination 2050, the Boston Region MPO has continued to use investment programs—particularly its Complete Streets and Bicycle Network and Pedestrian Connections programs—that support the implementation of Complete Streets projects. In the Unified Planning Work Program, the MPO budgets to support these projects, such as the MPO’s Bicycle and Pedestrian Support Activities program, corridor studies undertaken by MPO staff to make conceptual recommendations for Complete Streets treatments, and various discrete studies aimed at improving pedestrian and bicycle accommodations.

MassDOT developed the Congestion in the Commonwealth 2019 report to identify specific causes of and impacts from traffic congestion on the NHS. The report also made recommendations for reducing congestion, including addressing local and regional bottlenecks, redesigning bus networks within the systems operated by the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) and the other regional transit authorities, increasing MBTA capacity, and investigating congestion pricing mechanisms such as managed lanes. These recommendations guide multiple new efforts within MassDOT and the MBTA and are actively considered by the Boston Region MPO when making planning and investment decisions.

The Program for Mass Transportation (PMT) is the MBTA’s long-range capital planning document. It defines a 25-year vision for public transportation in eastern Massachusetts. The MBTA’s enabling legislation requires it to update the PMT every five years and to implement the policies and priorities outlined in it through the annual Capital Investment Plan (CIP). MassDOT’s Office of Transportation Planning will lead the process for updating the 2024 PMT.

MassDOT and the MBTA released the most recent PMT, Focus40, in 2019. Focus40 aims to position the MBTA to meet the transit needs of the Greater Boston region through 2040. Complemented by the MBTA’s Strategic Plan and other internal and external policy and planning initiatives, Focus40 serves as a comprehensive plan guiding all capital planning initiatives at the MBTA. These initiatives include the Rail Vision plan, which will inform the vision for the future of the MBTA’s commuter rail system; the Bus Network Redesign (formerly the Better Bus Project), the plan to re-envision and improve the MBTA’s bus network; and other plans. The Boston Region MPO continues to monitor the status of Focus40 and related MBTA modal plans to inform its decision-making about transit capital investments, which are incorporated in the TIP and LRTP.

MetroCommon 2050, which was developed by the Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC) and adopted in 2021, is Greater Boston’s regional land use and policy plan. MetroCommon 2050 builds off of MAPC’s previous plan, MetroFuture (adopted in 2008), and includes an updated set of strategies for achieving sustainable growth and equitable prosperity in the region. The MPO considers MetroCommon 2050’s goals, objectives, and strategies in its planning and activities. MetroCommon 2050 also serves as the foundation for land use projections in Destination 2050.

The purpose of the Congestion Management Process (CMP) is to monitor and analyze the mobility of people using transportation facilities and services, develop strategies for managing congestion based on the results of traffic monitoring, and move those strategies into the implementation stage by providing decision-makers in the region with information and recommendations for improving the transportation system’s performance. The CMP monitors roadways, transit, and park-and-ride facilities in the Boston region for safety, congestion, and mobility, and identifies problem locations.

Every four years, the Boston Region MPO completes a Coordinated Public Transit–Human Services Transportation Plan (CPT–HST), in coordination with the development of the LRTP. The CPT–HST supports improved coordination of transportation for seniors and people with disabilities in the Boston region. This plan also guides transportation providers in the Boston region who are developing proposals to request funding from the Federal Transit Administration’s Section 5310 Program. To be eligible for funding, a proposal must meet a need identified in the CPT–HST. The CPT–HST contains information about

The MPO adopted its current CPT–HST in 2023.

The MBTA and the region’s RTAs—the Cape Ann Transportation Authority (CATA) and the MetroWest Regional Transit Authority (MWRTA)—are responsible for producing transit asset management plans that describe their asset inventories and the condition of these assets, strategies, and priorities for improving the state of good repair of these assets. The Boston Region MPO considers goals and priorities established in these plans when developing its plans, programs, and activities.

The MBTA, CATA, and MWRTA are required to create and annually update Public Transit Agency Safety Plans that describe their approaches for implementing Safety Management Systems on their transit systems. The Boston Region MPO considers goals, targets, and priorities established in these plans when developing its plans, programs, and activities.

The COVID-19 pandemic has radically shifted the way many people in the Boston region interact with the regional transportation system. The pandemic’s effect on everyday life has had short-term impacts on the system and how people travel, and it may have lasting effects. State and regional partners have advanced immediate changes in the transportation network in response to the situation brought about by the pandemic. Some of the changes may become permanent, such as the expansion of bicycle, bus, sidewalk, and plaza networks, and a reduced emphasis on traditional work trips. As the region recovers from the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and the long-term effects become apparent, state and regional partners’ guidance and priorities are likely to be adjusted.

Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) staff conducted engagement activities throughout the development of Destination 2050. Engagement began in fall 2019 with the kick-off of the Needs Assessment and continued through the 30-day public comment period for the draft Long-Range Transportation Plan (LRTP) in June and July 2023.

This appendix summarizes the engagement activities and public input received during the different phases of LRTP development: Needs Assessment; vision, goals, and objectives revision; and project and program selection. It concludes with the comments received during the formal 30-day public comment period for the draft LRTP.

The MPO engaged a variety of stakeholders in the development of Destination 2050:

MPO staff used a variety of communication and engagement methods and channels to involve the public and solicit feedback:

Table C-1 provides a summary of the meetings, events, and content used in the Destination 2050 public engagement process. Staff also considered feedback and comments from engagement activities for other MPO programs and projects between 2019 and 2023 as input for the development of Destination 2050. Staff sought to include diverse and regionally representative perspectives by emphasizing engagement and relationship-building with historically underrepresented communities, and this input is reflected throughout Destination 2050. Through virtual and in-person engagement, MPO staff received more than 2,000 comments, ideas, and survey responses while developing Destination 2050.

Table C-1

Summary of Communication and Engagement Activities Used in the Development of Destination 2050

Type of Engagement |

Date |

Description |

MPO meetings |

2019–23 |

Presented periodic updates about the development of Destination 2050 in the MPO’s largest public forum |

Regional Transportation Advisory Council meetings |

2021–23 |

Held conversations, workshops, and activities to gather input on transportation needs, priorities, vision, goals, objectives, programs, and projects; provided periodic updates on Destination 2050 development |

MAPC subregional group meetings |

2020–22 |

Gathered input on transportation needs and priorities, and vision, goals, and objectives |

Focus groups |

2021 |

Collected input for Big Ideas scenario planning, including discussing and gathering feedback on driving forces, uncertainties, and proposed strategies |

Interviews |

2021–22 |

Interviewed stakeholders to gather input on needs, vision, goals, objectives, programs, and projects; and provided updates |

Transit Working Group Coffee Chats |

2021–22 |

Discussed and gathered feedback on transit-related topics |

Stakeholder group meetings |

2019–23 |

Gathered input on needs, vision, goals, objectives, programs, and projects from community and advocacy groups |

Partner events |

2019–23 |

Co-hosted meetings and events with other planning organizations to gather input on needs, vision, goals, objectives, programs, and projects |

Open houses |

2019–23 |

Shared information about MPO programs and gathered input on needs, vision, goals, objectives, programs, and projects |

Email content |

2019–23 |

Advertised opportunities for engagement |

Social media content |

2019–23 |

Advertised opportunities for engagement; engaged transportation advocates, community groups, and members of the public |

Surveys |

2019–23 |

Published surveys seeking input on transportation needs, vision, goals, objectives, and programs and projects, including surveys on the following topics:

|

FFY = federal fiscal year. MPO = metropolitan planning organization. TIP = Transportation Improvement Program. UPWP = Unified Planning Work Program.

Staff engaged stakeholders in exploratory scenario planning to inform the MPO’s consideration of future conditions in Destination 2050 through a series of focus groups in 2021, during which 53 participants from over 40 organizations in the Boston region identified driving forces they believe will shape transportation in the region, and strategies to respond to future conditions. Participants represented a wide range of stakeholder types and areas of expertise, including organizations that work with underrepresented communities.

The “big ideas” that stakeholders identified through these focus groups included the driving forces of climate change; new technologies and data; demographic, economic, and land use trends; consumer preferences, and policymaking. Strategies to address these forces included adaptation and emissions reduction; partnership and relationship building; flexibility; research and coordination with other areas of planning and policymaking; communications and engagement; and the equitable expansion of transportation options throughout the region.

More detailed information about this exploratory scenario planning engagement process and participants’ responses is available in the Big Ideas StoryMap.

The development of the Needs Assessment was informed by extensive engagement with stakeholders throughout the region. During the four-year development process for Destination 2050, MPO staff collected feedback about transportation needs from municipalities, transportation providers, advocates and community organizations, and members of the general public through a variety of engagement activities including focus groups, subregional meetings, public forums, and surveys.

Staff conducted broad and continuous engagement to collect feedback for the Needs Assessment, tracking needs expressed by stakeholders during targeted LRTP engagement efforts as well as from conversations, activities, and events in other venues or contexts. Staff prioritized the inclusion of a diverse range of perspectives throughout the region, including disadvantaged and historically underrepresented communities, and used demographic data to target, shape, and analyze the effectiveness of strategies to support equitable engagement efforts.

To collect feedback about transportation needs for Destination 2050, staff held a series of scenario planning focus groups (see Big Ideas for Scenario Planning above), which included sessions with interpretation and translated materials for communities with limited English proficiency; worked with municipal, agency, and advocacy partners to distribute surveys in seven languages; and held workshops and informational events at Advisory Council meetings and other public meetings. Throughout these engagement processes, staff built and deepened stakeholder relationships, helping to make MPO engagement more equitable and effective while laying the groundwork for ongoing efforts to hear and respond to the region’s transportation needs and priorities.

Input for the Needs Assessment was gathered from the following engagement activities:

To inform the update of the MPO’s planning framework for Destination 2050, staff engaged the public about visions, goals, and objectives for the region’s transportation future. During the fall of 2022 and winter of 2023, staff met with MAPC subregional groups and held workshops with the Advisory Council and MPO board members to hear stakeholders’ thoughts on how well the Destination 2040 planning framework aligned with their vision and goals and what updates and changes staff should pursue for the draft Destination 2050 vision, goals, and objectives. Feedback from these meetings and workshops informed significant updates to the Destination 2050 planning framework, including the integration of equity-oriented objectives across all goal areas, the addition of an engagement objective to the Transportation Equity goal, and the restructuring of several goal areas to reflect safety, mobility, and resilience priorities.

Staff primarily collected input for the Destination 2050 vision, goals, and objectives via a public survey that asked respondents to rank their transportation priorities, identify words and phrases that describe their ideal transportation system, and describe aspects of the Boston region’s transportation system that need to be improved. Staff publicized the survey across all general MPO communication channels and conducted extensive targeted outreach, adjusting outreach strategies based on live demographic and geographic response data to better engage underrepresented audiences.

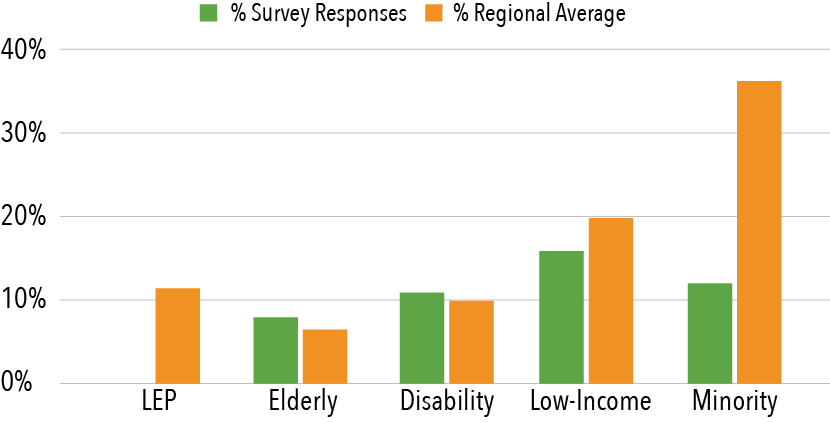

Staff received about 800 survey responses and about 675 responses to optional demographic questions at the end of the survey. A comparison of the demographic identification of survey respondents to the entire region’s demographics is shown in Figure C-1. Fifty-six percent of respondents gave a zip code associated with communities in the Inner Core, which is roughly consistent with the region’s population distribution. Distribution of gender, age, and household size was fairly even. Responses to a question about transportation mode use indicated that most respondents drove, either exclusively or in combination with other modes, while about 25 percent of respondents said they relied solely on transit or nonmotorized transportation.

Figure C-1

Demographics of Survey Respondents

Note: This survey recorded responses from 743 people.

Source: Boston Region MPO.

The responses to survey questions about the Destination 2050 planning framework highlighted several overarching themes related to visions and priorities for the region’s transportation system:

Figure C-2 represents 743 responses to a survey question asking participants to suggest three words to describe their ideal transportation system. The size and shading of each word correlate to the frequency with which the word was used. Words that are larger and bolder in color were more commonly expressed. Words or phrases that were similar in meaning were aggregated.

Figure C-2

Words to Describe an Ideal Transportation System

Note: This survey recorded responses from 729 people.

Source: Boston Region MPO.

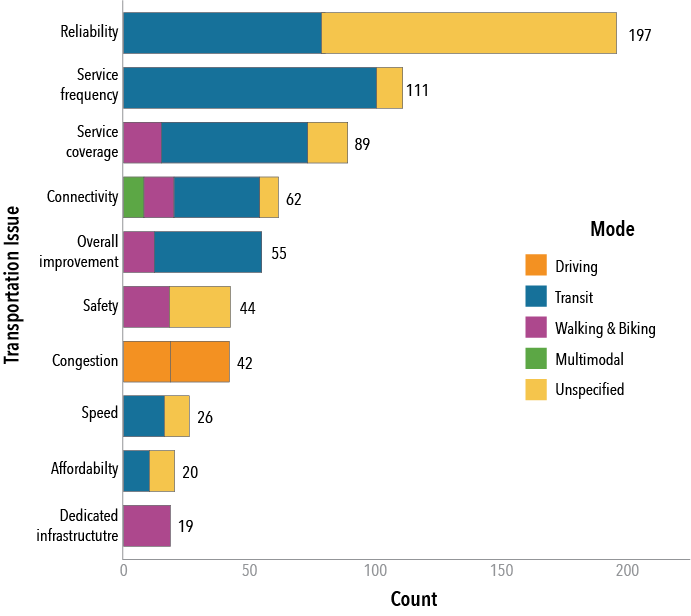

Figure C-3 shows 729 responses to an open-ended survey question asking participants to identify the most pressing transportation issues in the Boston region. Similar responses were aggregated and coded, and responses were categorized by mode and displayed in order of frequency.

Reliability was the top transportation challenge in the Boston region identified by survey respondents. Approximately one in four respondents called for improved reliability. Reliability was also often paired with other transportation challenges, such as frequency, safety, and speed. Among those who cited reliability in their response, more than half of them did not specify the mode of transportation where the issue manifests. Those who did, however, referred to delays and slow speeds of MBTA bus and rail rapid transit service.

Figure C-3

Transportation Challenges in the Boston Region

Note: This survey question recorded responses from 729 people.

Source: Boston Region MPO.

Other engagement activities during which staff discussed and gathered feedback on Destination 2050 vision, goals, and objectives included the following:

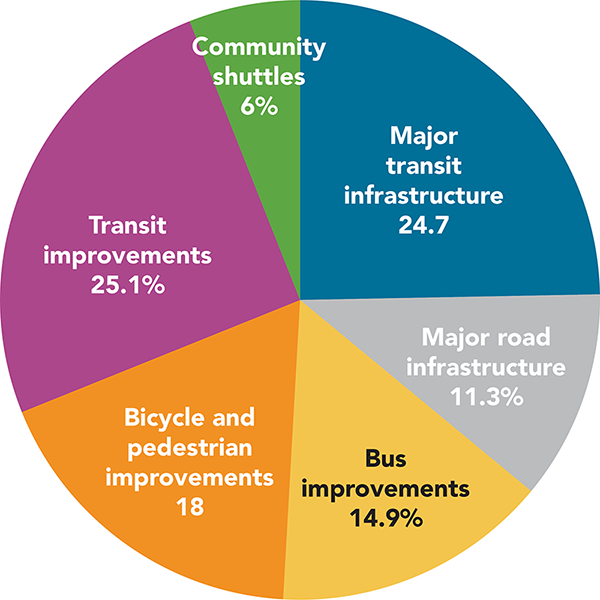

To inform the update of proposed LRTP investment programs and projects for Destination 2050, staff engaged stakeholders and members of the public on questions of their priorities for transportation system investments. During the spring of 2023, staff solicited comments and led discussions about investment priorities at MPO board and Advisory Council meetings, conducted interactive investment prioritization activities, and collected public input through an investment survey. Staff also received several comments and letters from project proponents and members of the public advocating for specific projects to be included in the Destination 2050 universe of projects.

The Destination 2050 investment survey asked respondents to allocate 100 tokens to different types of transportation system improvements. The survey helped the MPO to understand how well respondents felt the proposed investment programs aligned with public priorities for different types of transportation system investments and how they aligned with the MPO’s vision and goals. Staff advertised the survey on the MPO website, social media, and in MPO email communications. Staff also shared the survey during meetings and engagement events, as well as directly with stakeholders and partners, receiving about 300 total responses. Figure C-4 illustrates the average allocation to each type of investment listed in the survey.

Figure C-4

Average Funding Allocation: Responses from Investment Programs Survey

Note: This survey question recorded responses from 299 people.

Source: Boston Region MPO.

More than 150 people responded to an optional write-in question about additional investment priorities, and other people gave additional comments during other engagement activities such as Advisory Council and stakeholder meetings. These comments highlighted several themes, including respondents’ strong prioritization of investments to support transit system modernization, reliability, and safety; support for investments in transportation system connectivity within and beyond the Boston region; support for investments in pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure and connections; and the necessity of making transportation investments that are equitable and proactively respond to climate forces. Stakeholders also submitted written and verbal comments about investment programs to staff during the MPO’s consideration of Destination 2050 investment programs, including several comments in support of the inclusion of a new bikeshare support program in Destination 2050.Figure C-5 illustrates the percent of funding the MPO ultimately allocated to each investment program in Destination 2050.

Table C-1

Funding Allocated to MPO Investment Programs in Destination 2050

Investment Program |

Percentage Allocation, 2024–28 and 2034–50 |

Percentage Allocation, 2029–33 |

Funding Allocation, 2024–2050 |

Complete Streets |

45% |

30% |

$2,130,828,621 |

Major Infrastructure |

30% |

47% |

$1,643,425,636 |

Intersection Improvements |

12% |

10% |

$584,554,172 |

Bicycle Network and Pedestrian Connections |

5% |

5% |

$250,506,232 |

Transit Transformation |

5% |

5% |

$250,506,232 |

Community Connections |

2% |

2% |

$100,202,493 |

Bikeshare Support |

1% |

1% |

$50,101,246 |

Total |

|

|

$5,010,124,631 |

Note: Years are federal fiscal years

Source: Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization.

During discussions about investment program sizing and project selection, the MPO received comment letters and heard comments from proponents and members of the public supporting the following projects:

Concurrently with the development of Destination 2050, MPO staff developed an updated Coordinated Public Transit-Human Services Transportation Plan (Coordinated Plan) with the participation of public, private, and nonprofit transportation representatives, human services providers, and members of the public. Staff collected input about unmet transportation needs as well as strategies and priorities for addressing those needs from organizations and stakeholders that work with and represent seniors and people with disabilities.

Engagement activities for the Coordinated Plan included the following:

Staff also collected information about human services transportation needs and priorities to include in the Coordinated Plan from other sources:

While the 2023 Coordinated Plan contains results in more detail, several overarching themes related to human services transportation needs, strategies and actions, and priorities were identified:

An additional priority staff identified was the inclusion of riders and other stakeholders in human services transportation planning, and a desire for more institutional support for regional collaboration. Through the development of the next Coordinated Plan, staff will continue to consider feedback and pursue conversations about the ideal role for the MPO in supporting regional human services transportation coordination. Information and input from the development of the 2023 Coordinated Plan was included throughout Destination 2050, including the Needs Assessment, planning framework, and investment programs.

Staff emphasized the inclusion of input from environmental organizations, advocates, institutions, and agencies in the development of Destination 2050 and consulted with these stakeholders on the resilience of the transportation system and equitable adaptation to climate forces affecting the region’s future. Engagement activities included the following:

Feedback gathered from this engagement was central to the development of the Needs Assessment and Destination 2050 vision, goals, and objectives, including the development of a new resilience goal area.

Building and strengthening relationships with advocacy and community organizations throughout the region was at the core of the engagement undertaken to support the development of Destination 2050, and it will be critical to the success and effectiveness of future engagement efforts. Throughout the development of Destination 2050, staff met regularly with several transportation advocacy organizations and continued to expand these touchpoints to ongoing MPO work. Engagement activities for Destination 2050 sought not just to collect public input, but also to build awareness about the MPO, capacity for public participation in transportation planning, and trust among the region’s communities, particularly those who are underrepresented in the planning process.

A central element of the Long-Range Transportation Plan (LRTP) is a list of regionally significant transportation projects selected by the MPO. In order to create that list, the MPO first created a universe of projects list that included all potential projects that could be considered for inclusion in Destination 2050. Those projects came from the following sources:

The Destination 2050 universe of projects is presented in four tables:

Table D-1

Destination 2040 Project Status

| Municipality |

Proponent/Source |

Project |

MassDOT ID |

Design Status |

Funding Status |

Funding Agency |

Cost Estimate |

MAPC Subregion |

MassDOT Highway District |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Ashland |

Ashland |

Reconstruction of Pond Street |

604123 |

Under construction |

Funded FFY 2020 |

MPO |

$19,667,628 |

MWRC |

3 |

N/A |

Boston |

MassDOT |

Roadway, Ceiling, Arch, and Wall Reconstruction and Other Control Systems in Sumner Tunnel |

606476 |

Advertised for construction (6/26/2021) |

Funded FFYs 2021–23 |

MPO, MassDOT |

$136,190,450 |

ICC |

6 |

N/A |

Boston |

Massport |

Roadway Reconstruction–Cypher Street, E Street, and Fargo Street |

608807 |

PS&E Received (as of 09/28/2022) |

Funded with non-federal dollars |

Massport |

$20,287,865 |

ICC |

6 |

This project likely does not meet MPO criteria for including this project in Destination 2050. |

Boston |

Boston |

Reconstruction of Rutherford Avenue |

606226 |

25% Package Received – Resubmission (as of 10/05/2020) |

Funded FFYs 2026–27 in FFYs 2023–27 TIP |

MPO |

$176,570,936 |

ICC |

6 |

Listed in Table 2. Baseline readiness scenario for FFYs 2024-28 TIP moves first year to FFY 2028. |

Boston |

MassDOT |

Allston Multimodal Project |

606475 |

PRC Approved (03/30/2018) |

Funded in FFYs 2030–34 time band in Destination 2040 |

MassDOT |

$675,500,000 |

ICC |

6 |

Listed in Table 3. Likely to require elevated NEPA review. |

Cambridge, Somerville, Medford |

MBTA |

Green Line Extension to College Avenue with Union Square Spur |

1570 |

In service |

Funded FFYs 2016–21 |

MPO, MassDOT, MBTA |

$190,000,000 |

ICC |

6 |

N/A |

Everett |

Everett |

Reconstruction of Ferry Street |

607652 |

Under construction |

Funded FFY 2021 |

MPO |

$33,252,903 |

ICC |

4 |

N/A |

Framingham |

Framingham |

Intersection Improvements at Route 126 and Route 135/MBTA and CSX Railroad |

606109 |

PRC Approved (05/13/2010) |

Funded in FFYs 2030–34 and 2035–39 time bands in Destination 2040 |

MPO |

$115,000,000 |

MWRC |

3 |

Listed in Table 3. |

Hopkinton, Westborough |

MassDOT |

Reconstruction of Interstate 495 and Interstate 90 Interchange |

607977 |

Advertised for Construction (10/30/2021) |

Funded in FFYs 2023–27 in FFYs 2023–27 TIP |

MassDOT |

$300,942,836 |

MWRC |

3 |

Listed in Table 2. |

Lexington |

Lexington |

Route 4/225 (Bedford Street) and Hartwell Avenue (Lexington) |

TBD |

Pre-PRC Approval |

Funded in FFYs 2030–34 time band in Destination 2040 |

MPO |

TBD |

MAGIC |

4 |

Listed in Table 4. |

Lynn |

Lynn |

Reconstruction of Western Avenue |

609246 |

PRC Approved (12/06/2018) |

Funded in 2027 in FFYs 2023–27 TIP |

MPO |

$40,980,000 |

ICC |

4 |

This project likely does not meet MPO criteria for including this project in Destination 2050. |

Natick |

MassDOT |

Bridge Replacement, Route 27 (North Main Street) over Route 9 (Worcester Street), and Interchange Improvements |

605313 |

25% Package Received – Resubmission (05/16/2022) |

Funded in FFY 2024 in FFYS 2023–27 TIP |

MassDOT |

$75,677,350 |

MWRC |

3 |

Listed in Table 2. Funded with CRRSAA Funds. |

Newton, Needham |

Newton, Needham |

Reconstruction of Highland Avenue, Needham Street, and Charles River Bridge |

606635 |

Under construction |

Funded FFYs 2019–20 |

MPO |

$26,205,992 |

ICC |

6 |

N/A |

Quincy |

MassDOT |

New connection from Burgin Parkway over the MBTA |

606518 |

Construction complete |

Funded with non-federal dollars |

MassDOT |

$9,156,557 |

ICC |

6 |

N/A |

Somerville |

Somerville |

McGrath Boulevard Construction |

607981 |

PRC Approved (05/19/2014) |

Funded in 2027 in FFYs 2023–27 TIP |

MPO |

$88,250,000 |

ICC |

4 |

Listed in Table 2. |

Walpole |

Walpole |

Reconstruction on Route 1A (Main Street) |

602261 |

Under construction |

Funded in FFY 2020 |

MPO |

$19,790,904 |

TRIC |

5 |

N/A |

Watertown |

Watertown |

Rehabilitation of Mount Auburn Street (Route 16) |

607777 |

75% Package Received (as of 10/18/2022) |

Funded in 2027 in FFYs 2023–27 TIP |

MPO |

$27,899,345 |

ICC |

6 |

This project likely does not meet MPO criteria for including this project in Destination 2050. |

Woburn |

Woburn |

Bridge Replacement, New Boston Street over MBTA |

604996 |

Under construction |

Funded in FFY 2021 |

MPO |

$23,549,743 |

NSPC |

4 |

N/A |

Note: Destination 2040 references two other projects that are funded in other MPOs' LRTPs: the Southborough and Westborough—Interstate 495 and Route 9 project in Southborough and Westborough and the South Coast Rail project.

CRRSAA = Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act. FFY = federal fiscal year. ICC = Inner Core Committee. MAGIC = Minuteman Advisory Group on Interlocal Coordination. MAPC = Metropolitan Area Planning Council. MassDOT = Massachusetts Department of Transportation. MBTA = Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. MPO = metropolitan planning organization. MWRC = MetroWest Regional Collaborative. N/A = not applicable. NSPC = North Suburban Planning Council. PRC = Project Review Committee. PS&E = Plans, Specifications, and Estimates. TBD = to be determined. TIP = Transportation Improvement Program. TRIC = Three Rivers Interlocal Council.

Source: Boston Region MPO staff.

Table D-2

LRTP-Relevant Roadway Projects in FFYs 2023–27 TIP

Municipality |

Proponent/ |

Project |

Roadway (Federal) Functional Classification* |

MassDOT ID |

Design Status |

MPO Investment Program |

Current Program Year (in FFYs 2023–27 TIP) |

Cost Estimate |

MAPC Subregion |

MassDOT Highway District |

LRTP Status |

Notes |

Boston |

Boston |

Reconstruction of Rutherford Avenue |

Principal Arterial – Other |

606226 |

25% Package Received – Resubmission 1 (as of 10/05/2020) |

Major Infrastructure |

2025–27 |

$176,570,937 |

ICC |

6 |

In Destination 2040 (in FFYs 2020–24 and 2025–29 time bands) |

Proposed for funding in FFYs 2027–30 per TIP Readiness Days. |

Hopkinton, Westborough |

MassDOT |

Reconstruction of Interstate 495 and Interstate 90 Interchange |

Interstate |

607977 |

Advertised for construction (10/30/2021) |

N/A |

2023–27 |

$300,942,837 |

MWRC |

3 |

In Destination 2040 (in FFYs 2020–24 time band) |

Funded by MassDOT. Funded FFYs 2023–27 in FFYs 2023–27 TIP. |

Natick |

MassDOT |

Bridge Replacement, Route 27 (North Main Street) over Route 9 |

Principal Arterial – Other |

605313 |

25% Package Received – Resubmission 1 (as of 05/16/2022) |

Major Infrastructure |

2024 |

$75,677,350 |

MWRC |

3 |

In Destination 2040 (in FFYs 2025–29 time band) |

Funded with CRRSAA funds. Proposed Auxiliary lanes may affect roadway capacity. |

Norwood |

Norwood |

Intersection Improvements at Route 1 and University Avenue/Everett Street |

Principal Arterial – Other |

605857 |

25% Package Received – Resubmission 1 (as of 01/05/2021) |

Intersection Improvements |

2025–26 |

$26,573,400 |

TRIC |

5 |

N/A |

Project changes capacity through the addition of travel lanes. |

Somerville |

Somerville |

McGrath Boulevard Construction |

Principal Arterial – Expressway |

607981 |

PRC Approved (05/19/2014) |

Major Infrastructure |

2027 |

$88,250,000 |

ICC |

4 |

In Destination 2040 (in FFYs 2025–29 and 2030–34 time bands) |

Proposed for funding in FFYs 2027–30 per TIP Readiness Days. |

Wrentham |

Wrentham |

Construction of Interstate 495/Route 1A Ramps |

Interstate |

603739 |

75% Package Comments to design engineer (as of 08/02/2022) |

Major Infrastructure |

2024 |

$20,117,638 |

SWAP |

5 |

N/A |

Proposed for funding in FFY 2024 per TIP Readiness Days. |

* The federal functional classification listed above reflects the highest classification associated with roadways included in the project.

CRRSAA = Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act. FFY = federal fiscal year. ICC = Inner Core Committee. LRTP = Long-Range Transportation Plan. MAPC = Metropolitan Area Planning Council. MassDOT = Massachusetts Department of Transportation. MBTA = Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. MPO = metropolitan planning organization. MWRC = MetroWest Regional Collaborative. N/A = not applicable. NSPC = North Suburban Planning Council. PRC = Project Review Committee. SWAP = Southwest Advisory Planning Committee. TIP = Transportation Improvement Program. TRIC = Three Rivers Interlocal Council.

Source: Boston Region MPO Staff.

Table D-3

LRTP-Relevant MassDOT PRC-Approved Roadway Projects

| Municipality |

Proponent/Source |

Project |

Roadway (Federal) Functional Classification* |

MassDOT ID |

Design Status |

Potential MPO Investment Program |

Proposed Program Year |

Cost Estimate |

MAPC Subregion |

MassDOT Highway District |

LRTP Status |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Bellingham |

Bellingham |

Roadway Rehabilitation of Route 126 (Hartford Road), from 800 North of Interstate 495 NB off ramp to the Medway town line, including B-06-017 |

Principal Arterial/Other |

612963 |

PRC Approved (9/15/2022) |

Complete Streets |

2027 |

$10,950,000 |

SWAP |

3 |

N/A |

Project impacts on roadway capacity to be determined. |

Beverly |

Beverly |

Interchange Reconstruction at Route 128/Exit 19 at Brimbal Avenue (Phase II) |

Principal Arterial – Expressway |

607727 |

PRC Approved (2014) |

Major Infrastructure |

TBD |

$23,000,000 |

NSTF |

4 |

In Destination 2040 Project Universe (Active Highway Projects) |

Project would expand the interchange and add ramps. |

Boston |

MassDOT |

Allston Multimodal Project |

Interstate |

606475 |

PRC Approved (03/30/2018) |

N/A |

TBD |

$675,500,000 |

ICC |

6 |

Funded in FFYs 2030–34 time band in Destination 2040 (MassDOT-funded) |

NEPA Review: Environmental Impact Statement. Advertising date depends on availability of funding and completion of permitting. Earliest construction likely FFYs 2026–33. |

Boston |

Boston |

Bridge Preservation, Cambridge Street over MBTA |

Principal Arterial – Other |

612989 |

PRC Approved (12/21/2022) |

Complete Streets |

2026 |

$15,400,000 |

ICC |

6 |

N/A |

Project may add roadway capacity. |

Canton, Dedham, Norwood |

MassDOT |

Interchange Improvements at Interstate 95 / Interstate 93 / University Avenue / Interstate 95 Widening |

Interstate |

87790 |

25% submitted (7/25/2014) |

Major Infrastructure |

TBD |

$202,205,994 |

TRIC |

6 |

In Destination 2040 Project Universe (Active Highway Projects) |

Project may add roadway capacity. |

Concord |

Concord |

Reconstruction and Widening on Route 2, from Sandy Pond Road to Bridge over MBTA/B&M Railroad |

Principal Arterial Other |

608015 |

PRC approved (2014) |

Major Infrastructure |

TBD |

$8,000,000 |

MAGIC |

4 |

In Destination 2040 Project Universe (Active Highway Projects) |

N/A |

Concord |

Concord |

Improvements and Upgrades to Concord Rotary (Routes 2/2A/119) |

Principal Arterial Other |

602091 |

PRC Approved (02/25/1997) |

Major Infrastructure |

TBD |

$103,931,250 |

MAGIC |

4 |

In Destination 2040 Project Universe (Active Highway Projects) |

N/A |

Framingham |

Framingham |

Intersection Improvements at Route 126/Route 135/MBTA and CSX Railroad |

Principal Arterial/Other |

606109 |

PRC Approved 05/13/2010 |

Major Infrastructure |

TBD |

$115,000,000 |

MWRC |

3 |

Funded in FFYs 2030–34 and 2035–39 time bands in Destination 2040 (MPO-funded) |

Project impacts on roadway capacity to be determined. |

Malden Revere, |

MassDOT |

Improvements at Route 1 |

Principal Arterial – Expressway |

610543 |

PRC approved (2019) |

Major Infrastructure |

2027 |

$7,210,000 |

ICC |

4 |

In Destination 2040 Project Universe (Active Highway Projects) |

N/A |

Malden, Revere, Saugus |

MassDOT |

Reconstruction and Widening on Route 1, from Route 60 to Route 99 |

Principal Arterial – Expressway |

605012 |

PRC Approved (09/10/2007) |

Major Infrastructure |

TBD |

$172,500,000 |

ICC |

4 |

In Destination 2040 Project Universe (Active Highway Projects) |

N/A |

Randolph |

Randolph |

Interstate 93/Route 24 Interchange |

Interstate |

610540 |

PRC Approved (08/15/2019) |

Major Infrastructure |

TBD |

$14,420,700 |

TRIC |

6 |

N/A |

Project may include capacity adding elements. However, per District 6, This specific project has not seen any advancement since initiation. Some elements of the scope have been implemented through interim improvements. Project may be deactivated. |

Revere, Saugus |

Revere, Saugus |

Roadway Widening on Route 1 North (Phase 2) |

Principal Arterial – Expressway |

611999 |

PRC approved (2021) |

Major Infrastructure |

TBD |

$2,397,600 |

ICC |

4 |

In Destination 2040 Project Universe (Active Highway Projects) |

N/A |

Salem |

MassDOT |

Reconstruction of Bridge Street, from Flint Street to Washington Street |

Principal Arterial Other |

612990 |

25% submitted (8/20/2004) |

Complete Streets |

TBD |

$24,810,211 |

NSTF |

4 |

In Destination 2040 Project Universe (Active Highway Projects) |

Project would add a separated bi-directional path along the north side of the roadway. |

Woburn, Reading, Stoneham, Wakefield |

MassDOT |

Interchange Improvements to Interstate 93/Interstate 95 |

Interstate |

605605 |

PRC-Approved 05/14/2009 |

Major Infrastructure |

TBD |

$276,708,768 |

NSPC |

4 |

In Destination 2040 Project Universe (Active Highway Projects) |

Project may add roadway capacity. |

* The federal functional classification listed above reflects the highest classification associated with roadways included in the project.

FFY = federal fiscal year. ICC = Inner Core Committee. LRTP = Long-Range Transportation Plan. MAGIC = Minuteman Advisory Group on Interlocal Coordination. MAPC = Metropolitan Area Planning Council. MassDOT = Massachusetts Department of Transportation. MBTA = Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. MPO = metropolitan planning organization. MWRC = MetroWest Regional Collaborative. N/A = not applicable. NEPA = National Environmental Policy Act. NSPC = North Suburban Planning Council. PRC = Project Review Committee. SWAP = Southwest Advisory Planning Committee. TBD = to be determined.

Table D-4

LRTP-Relevant Conceptual Roadway Projects

| Municipality |

Proponent/Source |

Project |

Roadway Classification |

Potential MPO Investment Program |

Design Status |

Program Year |

Cost Estimate |

MAPC Subregion |

MassDOT Highway District |

LRTP Status |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Boston |

TBD |

Charlestown Haul Road |

Minor arterial, but proximate to the Tobin Bridge |

TBD |

Pre-PRC Approval |

N/A |

TBD |

ICC |

6 |

In Destination 2040 Project Universe (Conceptual Highway Projects) |

Project would construct an off-road truck route on the alignment of a freight spur that leads to Massport's Moran Terminal on the Mystic River near the Tobin Bridge. |

Braintree |

MassDOT |

I-93/Route 3 Interchange (Braintree Split) |

Interstate |

Major Infrastructure |

Pre-PRC Approval |

N/A |

$53,289,000 |

SSC |

6 |

In Destination 2040 Project Universe (Conceptual Highway Projects) |

Proposed improvements include the addition of a travel lane, a pair of auxiliary lanes, and associated acceleration lanes. A new entrance ramp is proposed along with restricting the use of an existing ramp. |

Braintree, Weymouth, Norwell |

MassDOT |

Route 3 South Widening (Braintree to Weymouth) |

Principal Arterial – Expressway |

Major Infrastructure |

Pre-PRC Approval |

N/A |

$800,000,000 |

SSC |

6 |

In Destination 2040 Project Universe (Conceptual Highway Projects) |

District 6 notes that this project has not advanced. |

Lexington |

Lexington |

Route 4/225 (Bedford Street) and Hartwell Avenue (Bedford/Hartwell Complete Streets Project) |

Principal Arterial – Other |

Major Infrastructure |

Pre-PRC Approval |

N/A |

TBD |

MAGIC |

4 |

In Destination 2040 (in FFYs 2030–34 time band) |

Specific nature of capacity impacts to be determined. |

Lynnfield, Reading |

TBD |

I-95 Capacity Improvements |

Interstate |

Major Infrastructure |

Pre-PRC Approval |

N/A |

$198,443,000 |

NSPC |

4 |

In Destination 2040 Project Universe (Conceptual Highway Projects) |

Specific nature of capacity impacts to be determined. |

Newton |

Newton |

New Route 128 Ramp to Riverside Station |

Interstate |

Major Infrastructure |

Pre-PRC Approval |

N/A |

$10,000,055 |

ICC |

6 |

In Destination 2040 Project Universe (Conceptual Highway Projects) |

Project status to be determined. |

Wilmington |

Wilmington |

I-93/Route 125/Ballardvale Street |

Interstate |

Major Infrastructure |

Pre-PRC Approval |

N/A |

TBD |

NSPC |

4 |

In Destination 2040 Project Universe (Conceptual Highway Projects) |

Specific nature of capacity impacts to be determined. |

Note: The federal functional classification listed above reflects the highest classification associated with roadways included in the project.

FFY = federal fiscal year. ICC = Inner Core Committee. MAGIC = Minuteman Advisory Group on Interlocal Coordination. MAPC = Metropolitan Area Planning Council. MassDOT = Massachusetts Department of Transportation. Massport = Massachusetts Port Authority. MWRC = MetroWest Regional Collaborative. NSPC = North Suburban Planning Council. PRC = Project Review Committee. SSC = South Shore Committee. SWAP = Southwest Advisory Planning Committee. Transportation Improvement Program.

The Boston Region MPO chose a list of projects to include in the LRTP (Table D-5). Each project was evaluated using quantitative and qualitative measurements of how it furthers the regional planning goals adopted by the MPO. (See Chapter 3.)

The evaluation criteria and the metrics that inform the evaluation are described below. The projects being evaluated come to MPO staff at different levels of preparation. A few projects may be defined at a 25 percent design level, generally the most design undertaken prior to a commitment to project funding in the TIP. Usually, however, there are only conceptual designs or project descriptions by proponents. The evaluation criteria have been specified in such a way that they can be applied to all candidate projects regardless of available project detail.

With a planning horizon to 2050, even well-defined projects can undergo significant changes, redesign, or rethinking before construction eventually begins. For these reasons, the evaluated projects are compared using a limited number of broad quantitative and qualitative measurements. These measurements examine the level of detail on what is known about existing conditions in the proposed project area. The effectiveness with which a project will address future deficiencies must be estimated by applying professional judgement to these preliminary project concepts. Cost estimates, in most instances developed by other agencies than the MPO, are similarly preliminary.

The MPO has defined six goal areas:

The measurements used in this analysis are intended to reflect how effectively a project would further these MPO goals were it to be completed. Given the distant time horizon, preliminary designs, and complexity of the transportation activity being evaluated, these measurements were not as detailed as Transportation Improvement Program (TIP) evaluations.

The scarcity of applicable data and very preliminary nature of project plans make any projection of benefits or disbenefits insufficiently reliable in the goal areas of Equity or Clean Air and Healthy Communities. As a result, evaluation procedures and scores have not been developed for those two goal areas as part of the LRTP. However, all projects will be rescored for all six goal areas if they are included in the TIP.

The scoring methodology for the four goal areas scored here (safety, mobility and reliability, access and connectivity, and resiliency) builds upon project scoring procedures that were used in the preceding LRTP, Destination 2040. The evaluation and scoring procedures have been modified to reflect Destination 2050 goals.

Below are descriptions of specific evaluation procedures for the four goal areas.

The elements that go into the development of the safety scores are shown in Table D-5. Additional data, not used directly in scoring but that inform and corroborate the safety scores, are also shown.

The safety scores are developed by considering the number and severity of crashes in the project areas, the number of vehicles that pass through, the expected project cost, and the nature of the roadway improvements proposed. Characterizing the nature of the proposed improvements is the scoring aspect that is most dependent on professional judgement.

The Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT) maintains a database of statewide crashes that is updated annually. Crash data from 2016 is now available and crashes that occurred during the 2014–16 period were used in developing safety scores. Crashes range widely in severity and are measured using the concept of equivalent property damage only (EPDO).

The EPDO formula used for the evaluations has recently been revised. This method of assessing crash severity is a weighting system aligned with calculated crash costs based on a 2017 Federal Highway Administration report, Crash Costs for Highway Safety Analyses. The EPDO formula used in this evaluation counts all crashes that occurred in a project area over the three-year period and adds the number of crashes involving bodily injury multiplied by 20.

Crash risk is calculated by comparing the EPDO value with the number of vehicles that enter the project area during an average weekday. Project area traffic volumes are estimated using recent traffic studies by the Central Transportation Planning Staff, project development proponents, MassDOT’s online traffic count database, or the MPO’s travel demand model.

Dividing the EPDO value by vehicles per year is a measurement of risk. This fraction is usually multiplied by 100,000,000 to give EPDO per hundred million vehicles. The evaluated projects are then divided into two equal-sized groups, high risk (score=one) and low risk (score=two), based solely on this risk calculation.

The second scoring index is project cost divided by the project area EPDO. This quotient resembles a cost-benefit ratio, but its meaning is more limited. A large EPDO value implies some degree of obsolete or deficient roadway design in the project area. Any reconstruction activity is required to meet current design and safety standards, so it is assumed that the project will improve safety.

There is no expectation that bringing the project area up to current design standards will eliminate all crashes, but EPDO serves as a proxy for potential safety improvement. A low cost per EPDO implies that the proposed investment that will bring the entire project area up to current standards will improve safety and will help to reduce a comparatively large number of crashes. The evaluated projects are divided into two equal-sized groups: low cost per EPDO (score=one) and high cost per EPDO (score=two).